On This Date in History, May 31, 1921: The Tulsa Race Massacre

Share

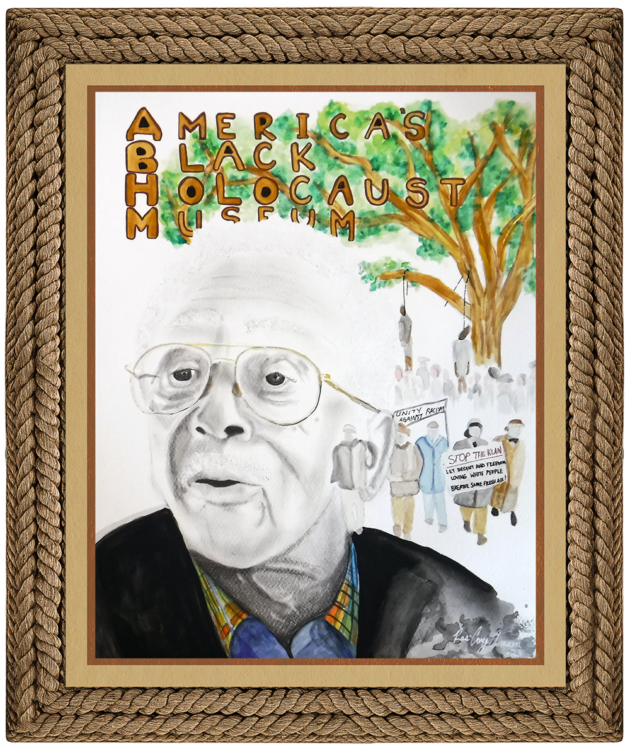

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From Wikipedia

The Greenwood District in happier days, pre-riot. The building with the tile roof, midway back on the left, was the only one still standing since the riot. It now serves as the Greenwood Cultural Center. (See photo below)

On May 31 and June 1, 1921, the white citizens of Tulsa, Oklahoma, attacked the city’s black citizens, following the publication of a sensationalized story of a black man assaulting a white woman in an elevator. The Greenwood District, also known as the “Black Wall Street,” the wealthiest black community in the United States, was burned to the ground.

Flourishing businesses burn during the riot. The area was completely decimated. (Tulsa Historical Society)

In one of the nation’s worst acts of terrorism and racial violence, 35 square blocks of homes and businesses were torched by mobs of angry whites.

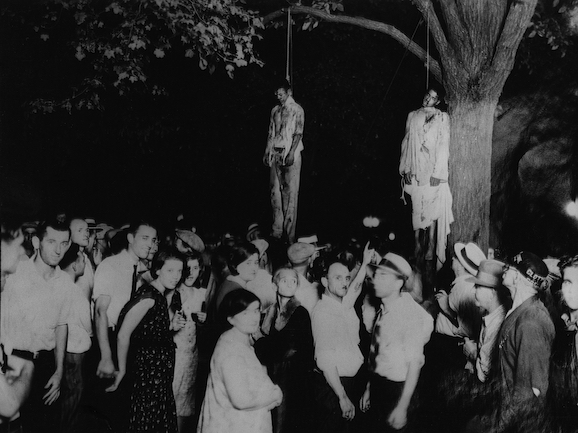

The riot began because of the alleged assault of a white elevator operator, 17-year old Sarah Page, by an African American shoeshiner, 19-year old Dick Rowland (the case against Mr. Rowland was eventually dismissed). The Tulsa Tribune got word of the incident and chose to publish the story in the paper on May 31, 1921. Shortly after the newspaper article surfaced, there was news that a white lynch mob was going to take matters into its own hands and kill Dick Rowland.

A group of armed white men congregated outside the jail and, subsequently, a group of African American men joined the assembled crowd in order to protect Dick Rowland.

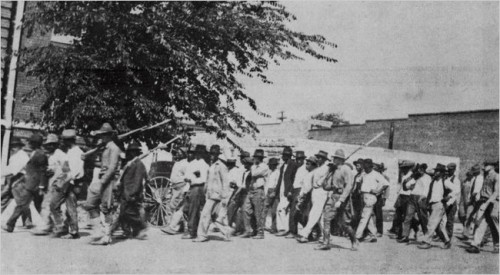

Black men marching to the jail to protect Rowland from being lynched, before the start of the race riot. (Tulsa Historical Society)

There was an argument in which a white man tried to take a gun from a black man, and the gun fired a bullet up into the sky. This incident promoted many others to fire their guns, and the violence erupted on the evening of May 31, 1921. Whites flooded into the Greenwood district and destroyed the businesses and homes of African American residents. No one was exempt from the violence of the white mobs; men, women, and even children were killed by the mobs.

Troops were eventually deployed on the afternoon of June 1, but by that time there was not much left of the once thriving Greenwood district. Over 600 successful businesses were lost. Among these were 21 churches, 21 restaurants, 30 grocery stores and two movie theaters, plus a hospital, a bank, a post office, libraries, schools, law offices, a half-dozen private airplanes and even a bus system. Note—It was a time when the entire state of Oklahoma had only two airports, yet six blacks owned their own planes.

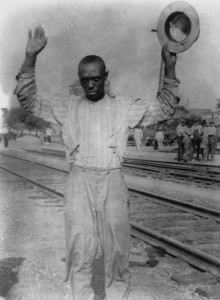

A black man being detained during the riot, while white men watch from across the tracks. (Courtesy of the Tulsa Historical Society.)

It was suspected by many blacks that the entire thing was planned because many white men, women and children stood on the borders of the city and watched as blacks were shot, burned and lynched. In addition, some of the black-owned airplanes were stolen by the white mob and used to throw cocktail bombs & dynamite sticks from the sky. Property damage totaled $1.5 million (1921). Although the official death toll claimed that 26 blacks and 13 whites died during the fighting, most estimates are considerably higher. At the time of the riot, the American Red Cross estimated that over 300 persons were killed. The Red Cross also listed 8,624 persons in need of assistance, in excess of 1,000 homes and businesses destroyed, and the delivery of several stillborn infants.

By A. G. Sulzberger, The New York Times, June 19, 2011

TULSA, Okla. — With their guns firing, a mob of white men charged across the train tracks that cut a racial border through this city. A 4-year-old boy named Wess Young fled into the darkness with his mother and sister in search of safety, returning the next day to discover that their once-thriving black community had burned to the ground.

Homes of African Americans burning during the race riot. (Tulsa Historical Society.)

The Tulsa race riot of 1921 was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms or even in private. Blacks and whites alike grew into middle age unaware of what had taken place.

Wess Young was 4 years old when he fled with his family from the riot. (Brandi Simons, The New York Times.)

Ever since the story was unearthed by historians and revealed in uncompromising detail in a state government report a decade ago — it estimated that up to 300 people were killed and more than 8,000 left homeless — the black men and women who lived through the events have watched with renewed hope as others worked for some type of justice on their behalf.

But even as the city observed the 90th anniversary this month, the efforts to secure recognition and compensation have produced a mixed record of success.1

Memorial on the grounds of the Greenwood Cultural Center. (Brandi Simon, The New York Times)

The riot will be taught for the first time in Tulsa public schools next year but remains absent in many history textbooks across the United States. Civic leaders built monuments to acknowledge the riot, including a new Reconciliation Park, but in the wake of failed legislative and legal attempts, no payments were ever delivered for what was lost.

Griot’s Note:

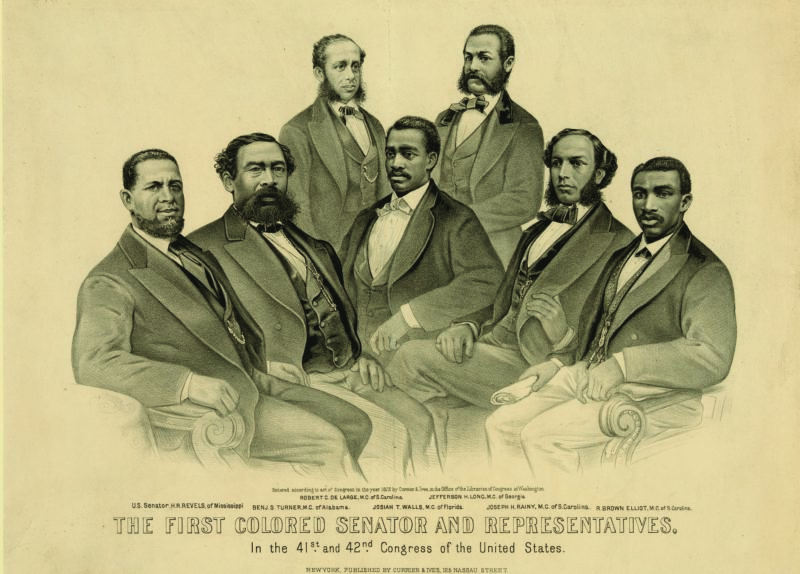

1The Greenwood Cultural Center, dedicated on October 22, 1995, was created as a tribute to Greenwood’s history and as a symbol of hope for the community’s future. The center has a museum, an African American art gallery, a large banquet hall, and housed the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame until 2007. The total cost of the center was almost $3 million. The cultural center is a very important part of the reconstruction and unity of the Greenwood Historical District.The Greenwood Cultural Center sponsors and promotes education and cultural events preserving African American heritage. It also provides positive images of North Tulsa to the community, attracting a wide variety of visitors, not only to the center itself, but also to the city of Tulsa as a whole.

The Greenwood Cultural Center has an extensive exhibit about the Tulsa Race Riot.

In 2011, the Greenwood Cultural Center lost 100% of its funding from the State of Oklahoma. As a result, the center may be forced to close its doors. A fundraising campaign is now underway to try to raise private funds to keep the educational and cultural facility open.

Read the entire NYT story here.

Read more Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.