John Carter: A Scapegoat for Anger

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Griot: Stephanie Harp, MA

Copy Editor: Fran Kaplan, EdD

LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS. In April of 1927, an eleven-year-old girl was murdered. In May, an angry posse grabbed a man who didn’t do it and hung him from a telephone pole.

The Powder Keg

On April 12, 1927, a little white girl, Floella McDonald, disappeared on her way home from the library. For three weeks, family, friends, and officials searched for her. Finally, following a foul smell, the black janitor of the First Presbyterian Church found her body in the church’s bell tower. Her head had been bashed in with a brick found nearby. A teenager, Lonnie Dixon, the church janitor’s son, was arrested and charged with rape and murder.1

Many whites were angry and wanted to “get” Lonnie themselves. Several thousand people went to the jail and demanded that police turn him over. Instead, Chief Burl Rotenberry sent Lonnie to an out-of-town jail, to keep him safe.

The Spark

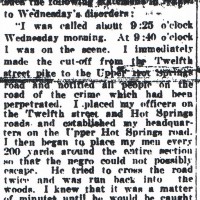

On the morning of May 4, two white women – Mrs. B.E. Stewart, age forty-five, and her daughter Glennie, seventeen – were driving a wagon on a rural road, heading toward Little Rock. A black man approached them. Some accounts said the horses were out of control and the man grabbed the reins to help the women. Others said he jumped in the wagon, demanded whiskey, and knocked them to the ground. A car stopped and took Mrs. Stewart and Glennie to the hospital. The man ran into the woods. When the women’s family heard that a black man had jumped on their wagon, Sheriff Mike Haynie organized a posse. Hundreds of people came from Little Rock to help in the all-day search.2

After eight hours, two officers saw John Carter, a local black man. The previous summer, he had gone to jail for attacking a white woman with a hammer. He had escaped from a work crew four days earlier, the same day the janitor found Floella’s body. Some said Carter was mentally disabled. The posse grabbed him and put him into a car. As more and more searchers joined the crowd, some said they wouldn’t let police protect him as they’d protected Lonnie Dixon. Glennie Stewart arrived and identified him as the man who had attacked her and her mother.

The Explosion

Mob members took Carter to a telephone pole and hit him with a revolver. They told him to confess, and then to pray. Before he finished, someone put a rope around his neck and told him to climb on top of a car. When he couldn’t, he was pushed up. Peace Officers later said armed men threatened them when they tried to stop the lynching. Men holding the rope pulled John Carter up above the ground. Then someone drove the car out from under him and he swung in the air. A line of fifty men fired guns, striking Carter with more than two hundred bullets.

The crowd quickly grew to four hundred. The sheriff brought the coroner to write a report about John Carter’s death. Even though someone took a picture of the hanging body, with the crowd visible in the background, none of the mob members would admit they’d been there. The report said Carter had been killed “by parties unknown in a mob.”3

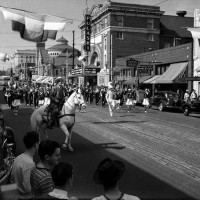

The mob voted to take Carter’s body to Little Rock and burn it. When they got to the city, they tied him to the car’s bumper and dragged him through the city for an hour, down Main Street and past police headquarters. Finally, at about 7:00 p.m., the mob stopped at Ninth and Broadway, the center of the black business district.4 They poured gasoline and kerosene over Carter’s body. They piled on boxes, tree limbs, and pews from the nearby Bethel A.M.E. Church, and lit the fire.5 More white people hurried to the area. The crowd was shouting, firing guns into the air, cursing, yelling, and dancing. The active mob was about seven thousand, with thousands more men, women, and children watching.

Mayor Charles Moyer and Police Chief Rotenberry had left the city and no one knew where they were. Major J.A. Pitcock, chief of detectives, wanted to take fifty men and stop the rioting. But the assistant police chief said he couldn’t give that order without hearing from city council. City council wouldn’t act without the mayor.

Governor John Martineau was out of town, too. When he heard what was happening, he called out the National Guard. Seventy soldiers arrived at 10 p.m. with guns, bayonets, and tear gas bombs. When they told the remaining one or two thousand people to go home, they did. A fire truck doused the fire. An ambulance took Carter’s remains to City Hall and then to the undertaker. People already had taken pieces of his body from the ashes, and they carried them around the city during the night.6

Soldiers reported seeing one person directing traffic with a charred arm torn from Carter’s burned body.

Epilogue

No one was ever charged or prosecuted for lynching John Carter. A jury deliberated for only twelve minutes before convicting Lonnie Dixon of killing Floella McDonald. He was executed in the electric chair on June 24, 1927, his sixteenth birthday.

Endnotes:

1 In those days, when black males had any sort of contact with white females, the males very often were charged with rape.

2 Sheriffs could deputize ordinary citizens when they needed help with a crisis or a search. “Deputize” means to give temporary authority to people who are not law enforcement officers.

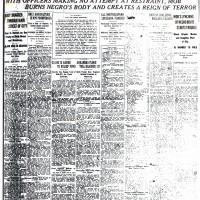

3 Most lynching victims were recorded as killed “by parties unknown.” Very often, photographs were taken of lynching scenes, and still no one was identified. The photograph of John Carter’s death appeared in Haldeman-Julius, The Story of a Lynching, 3.

4 Because of Jim Crow segregation, blacks and whites had to shop and do business in separate sections of town.

5 "When I was a little girl, my mother and I saw a lynch mob dragging the body of a Negro man through the streets of Little Rock . We were told to get off the streets. We ran. And by cutting through side streets and alleys, we managed to make it to the home of a friend. But we were close enough to hear the screams of the mob, close enough to smell the sickening odor of burning flesh. And, Mrs. Bates, they took the pews from Bethel Church to make the fire. They burned the body of this Negro man right at the edge of the Negro business section.” From the eyewitness account of Birdie Eckford, quoted in Bates, 62.

6 Burning the victim's body and collecting body parts as souvenirs were common occurrences in lynchings. So was having a photograph taken of the victim with his murderers and spectators.

Sources

This account is compiled from:

- April-June 1927 articles in these newspapers: The Arkansas Democrat, Arkansas Gazette, and The Chicago Defender. Read transcriptions of an original article written on the day after the lynching published in the Arkansas Gazette: Mob's Lynching of Negro Brute Starts Trouble (pdf)

- Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. The Story of a Lynching: A Exploration of Southern Psychology. Little Blue Book No. 1260. E. Haldeman-Julius, ed. Girard, KS: Haldeman-Julius Company, 1927.

- John Carter (Lynching of), The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, accessed August 8, 2012.

- Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

For more about John Carter and the rumors that surrounded his life, go to his entry in the Memorial to the Victims of Lynching. Read recent full report of the lynching and how it continues to haunt the community from an Arkansan historian here.

To read about Stephanie’s personal connection to the lynching of John Carter, click here.

NOTE: On February 15, 2013, Stephanie and George Fulton, great-grandson of John Carter, will join together in a public forum in Little Rock, AR, to explore the different perspectives on the lynching in the community. They now work together on a film and newsletter about the case. For more details, go here.

Stephanie Harp, MA, is a writer and journalist who holds a master’s degree in U.S. History from the University of Maine. Her family roots lie in Arkansas and Louisiana. Visit her blog about Race, Responsibility and Paying Attention in the Generations After Jim Crow.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

[…] A new page, Essays and Presentations, will feature my history, creative writing, and presentations. The first posted is an account of the lynching compiled from publications of the day. Coming soon will be a creative piece about the event. Both of the pieces have been published by America’s Black Holocaust Museum. […]

[…] the 1927 Little Rock lynching and my connection to it. Or perhaps you’ve read about it on America’s Black Holocaust Museum. In October, I presented my one aspect of my history research at Without Sanctuary: A Conference on […]

Based on what you wrote, it seems as though both Lonnie Dixon and John Carter were both hardened criminals who violently attacked random whites. It seems as though they got what they had coming to them.

Nobody deserves what these two were dealt! Patti

Being arrested and charged with murder is hardly proof that 16-year-old Lonnie Dixon was a “hardened criminal.” The evidence against him was circumstantial, at best. Neither is his conviction, in only 12 minutes and by a jury that was clearly not comprised of his peers. John Carter was murdered on the word of a 17-year-old girl, who was being encouraged by a mob. That is hardly evidence of hardened criminality, either. There is no way to know for certain, 86 years later, what actually happened in either case. But there are enough holes in the available documents to raise significant questions, at the very least. No one deserves to be murdered by an enraged mob while peace officers, who are charged with protecting citizens, look on but don’t intervene.

Kurt, let them try that these days and see what happens…you will need more than a army to calm down the city….how can you find somebody guilty in 12 mins???? no evidence no nothing… I’m sick of seeing the white man hide behind their justice system….

this is very sad to think that people where so cruel to accuse someone for only being black. having the time and place its sad that white people ever thought of doing this to blacks. and for lonnie i wanna say rest in peace may your soul rest in peace because i lost a friend that was your age due to a white man running him over and not caring so yeah.

It goes to show that this type of behavior still is present today ignorant prejudice White people is the norm in American society. I am sure these people are practicing so called Christians who believe they are right. One comment say they got what they deserve if that is true what do whites who murder, torture and rape Blacks deserve I believe and eye for and eye. There will come a time when Whites and Blacks who have committed crimes like this against humanity will answer for their sins. I am totally a shame to be called an American with this as a part of my American History. The totality of crimes against Blacks is alarming there is no amount of ink that can write down the crimes that were committed upon my people Christ would have to be crucified a million times to atone for these sins against humanity. May GOD help our wretched American Souls.

Every one here is Judging, do not judge lest ye be judge. I feel that past is past and what is important is that we learn to forgive not forget, but forgive and learn and teach each other wha t it really means to Love and live together as God would want us to live. We are all made in His image and we need to act like it. It doesn’t take much in today’s era 2021 to look up and around and know the difference between good and evil, right from wrong. TO comfort and spread joy, to love and show respect!