Remembering the Black Holocaust

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Sarah Terez Rosenblum, Express Milwaukee

Off the Cuff with Fran Kaplan

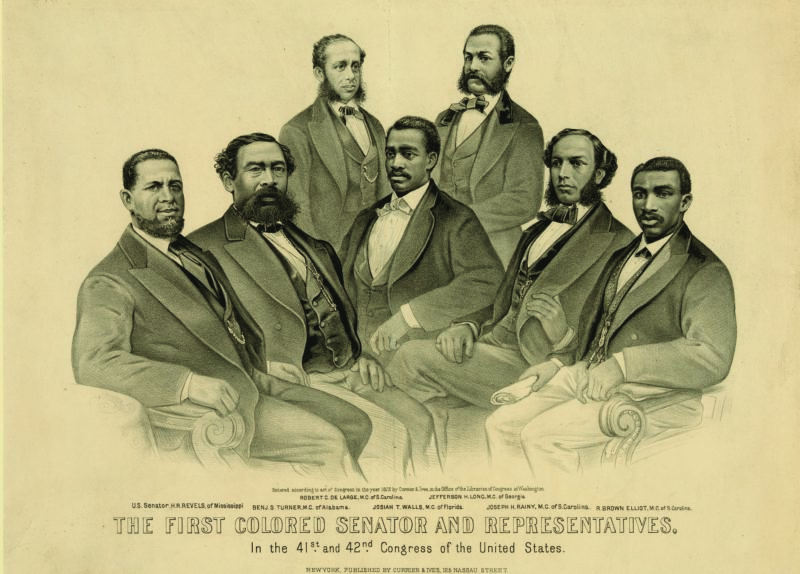

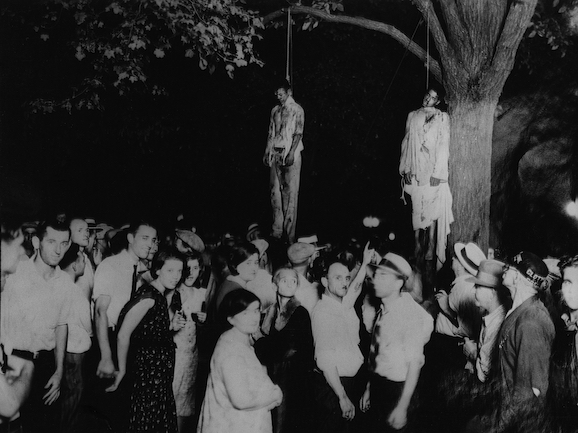

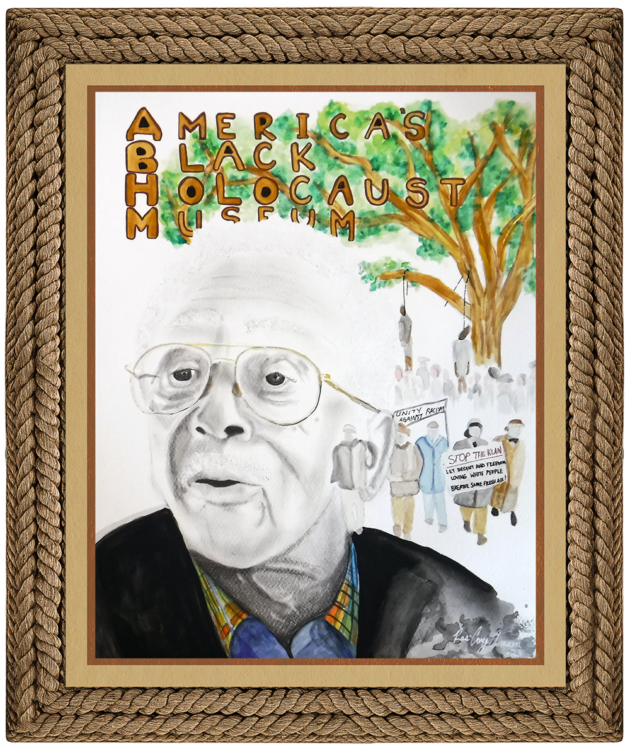

Fran Kaplan is nothing if not passionate. A dedicated educator, social worker and self-described “social justice activist,” Kaplan became involved with America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in 2006 when she spent a week interviewing James Cameron, the museum’s founder, for a film about his life. After his death and the closing of the 20-year-old museum, she remained in touch with his son. Her role as coordinator of ABHM’s Virtual Museum grew from that relationship. The Virtual Museum continues ABHM’s work online (abhmuseum.org), until it can reopen in brick-and-mortar form. Off the Cuff spoke with Kaplan about the project’s goals and race relations in general.

How would you describe the Black Holocaust Museum’s aims?

ABHM builds public awareness of the harmful legacies of slavery in America and promotes reconciliation and healing. We envision a society that remembers its past in order to shape a better future: an equitable society in which every person is equally valued and cared for, a country that is, in Dr. Cameron’s words, “a single and sacred nationality.”

What does your involvement entail?

As coordinator of ABHM’s Virtual Museum, I seek out and manage the resources—human and financial—that keep our online museum growing. I find volunteer academics and independent scholars to curate exhibits, along with student interns and community volunteers that produce other features. I also write grants and manage our local “offline” public programs, such as our popular film/dialogue series.

Why open a virtual museum? What are the benefits there?

In the 21st century, much of our lives are lived online. Information-based institutions are evolving to meet that reality. The Great Recession brought a significant reduction in funding. Buildings are expensive. Putting ABHM online was a financially prudent first step to its revival. Later we will reestablish our physical presence. Meantime, you can visit ABHM 24/7 for free—in your pajamas! Another benefit of going virtual has been discovering how many people around the world are interested in ABHM’s exhibits. The museum gets thousands of page views weekly from 200 countries.

Who do you see as your target demographic?

Americans aged 10 to 100—students, educators and the general public. The social studies taught in most American classrooms do not adequately prepare us to understand and repair our country’s long-standing racial divide. ABHM fills the gap by recounting the untold and seldom-told causes of that divide.

Milwaukee is widely known as one of the more racially segregated cities. How might the museum’s presence function against this backdrop?

By helping Milwaukeeans learn how our city came to be like this, in the context of our nation’s history, and by bringing black and non-black Milwaukeeans together in activities that build trust, deepen relationships, enable truthful exchanges and lay the groundwork for joint action.

Obviously we’re experiencing a cultural/political moment of heightened awareness around systemic racism. What role do you see the museum playing in this time of chaos?

ABHM teaches the difference between systemic (institutional) racism and personal prejudice, and how people have confronted both throughout history. We provide a safe place to discuss the issues.

As a white woman, do people ever question your involvement? What would be your response?

Sure, though they seldom ask me directly. Dr. Cameron welcomed non-black allies, calling us “freedom-loving whites.” ABHM works with black and white audiences. When I participated in the civil rights movement, black mentors explained why whites should help whites understand and make systemic change. I try to do that. I also do my work in consultation with our predominantly black board of directors and my African American colleagues, Brad Pruitt, ABHM’s community engagement coordinator, and Reggie Jackson, our Head Griot (docent/oral historian).

Obviously, the word “holocaust” is not reserved for Jews, however, it is commonly associated with the Jewish persecution by the Nazis, the Shoah. What are the pros and cons of using that word to describe black captivity in Africa through enslavement and up to the present day?

Being Jewish, I understand the urge to keep the term “holocaust” specific to the Shoah. When Dr. Cameron visited Yad V’Shem, the Shoah memorial in Jerusalem, he was struck by the similarities in the suffering of European Jews and African Americans, hence his museum’s name. A description of these similarities can be found at abhmuseum.org.

What is your ultimate goal for the project?

That one day, parents will bring their children to ABHM to wonder at the dinosaur-like fossils of the racial divide that we helped to heal long ago.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

DONT LEAVE YOUR BROTHER BEHIND AS YOU PROSPER.HE MAY TURN OUT TO BE VALUABLE IN FUTURE.BUILD BRIDGES BUT NOT WALLS.