Horror Drove Her From South. 100 Years Later, She Returned.

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Dan Barry, New York Times

In 1915, Mamie Kirkland and her family fled Ellisville, Miss., in fear that her father would be lynched. She swore she would never return. But at age 107, she made the journey.

…[Kirkland’s] father, Edward Lang, a laborer and aspiring minister, roused the house at 12:30 in the morning. “Rochelle, I got to leave,” she remembered him saying to her mother. “Get the children together.”

Family lore has it that people wanted to lynch her father and a friend named John Hartfield, and that the two men fled that night. The rest of the Langs — a mother and five children, including baby Lucille, who was nursing — left by train in the morning. It was 1915.

“We were just shaking,” Ms. Kirkland said.

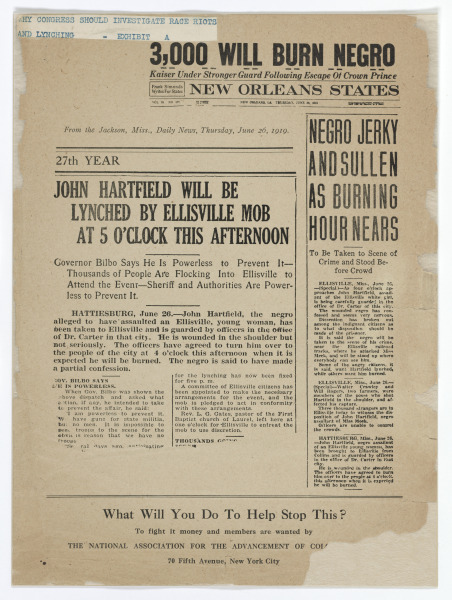

They settled in East St. Louis, Ill., where word later came that Mr. Hartfield had returned to Ellisville to be with his white girlfriend. This is undocumented family gospel. What is documented is that on June 26, 1919, white townspeople lynched him for allegedly raping a white woman.

The front page of The Jackson Daily News announced that Mr. Hartfield would be lynched at 5 p.m. “Governor Bilbo Says He Is Powerless to Prevent It,” the headline read. “Thousands of People Are Flocking Into Ellisville to Attend the Event.”

The [Ellisville, Mississippi,] population of 1,700 instantly multiplied as crowds spilled out of the Hotel Alice and into the open space along the train tracks. A postcard depicting the scene bears the caption: “Waiting for the Show to Start.”

Mr. Hartfield was dragged to a big gum tree and strung up. A rain of bullets from the crowd seemed to reanimate the corpse, which finally fell to the ground and was burned to ashes. Some took body parts as souvenirs.

In the Ellisville of today, little recalls the moment, other than the Hotel Alice. In a mayoral portrait gallery at City Hall, for example, the officeholder in 1919 is absent. And at Jones County Junior College, Roll 539 of the microfilm for the local newspaper, The Laurel Daily Leader, jumps from May 27, 1919, to Aug. 22, 1919 — as if the June lynching of Mr. Hartfield had never happened.

But it remained seared in collective memory. “I never saw him in my life, but I remember his name,” Ms. Kirkland said, adding, “Could have been my father.”

By then, it appears, the family had already endured mayhem in East St. Louis, where thousands of Southern black men like her father found work in industrial plants. In 1917, when Ms. Kirkland was 9, rioting white men, incensed by the job competition and changing demographics, burned down black neighborhoods and shot at those who fled. Dozens of black residents, maybe many more, died, and thousands were left homeless.

Read the full story here.

Read an eyewitness account of the lynching of John Hartfield by a reporter here.

Read more Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

Well, that sure does rid the notion that lynching was only a mob induced activity. And, quite a reason my father left the south as a young man, not to return or ever speak of his past.

Blessings to the brave Ms. Mamie.