How African Americans Changed the Meaning of the Civil War

Share

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Jarrod Showalter

The enslavement of African Americans was the root cause of the American Civil War. When the eleven Southern states seceded from the Union, however, the federal government did not plan to end slavery. Slaveholding states in the South seceded out of fear of slavery’s destruction after Abraham Lincoln was elected President. Lincoln wanted, first and foremost, to preserve the United States. When he first called for volunteer soldiers to crush the rebellion, the war was a conflict between white men, with little consideration for enslaved African and Native Americans.

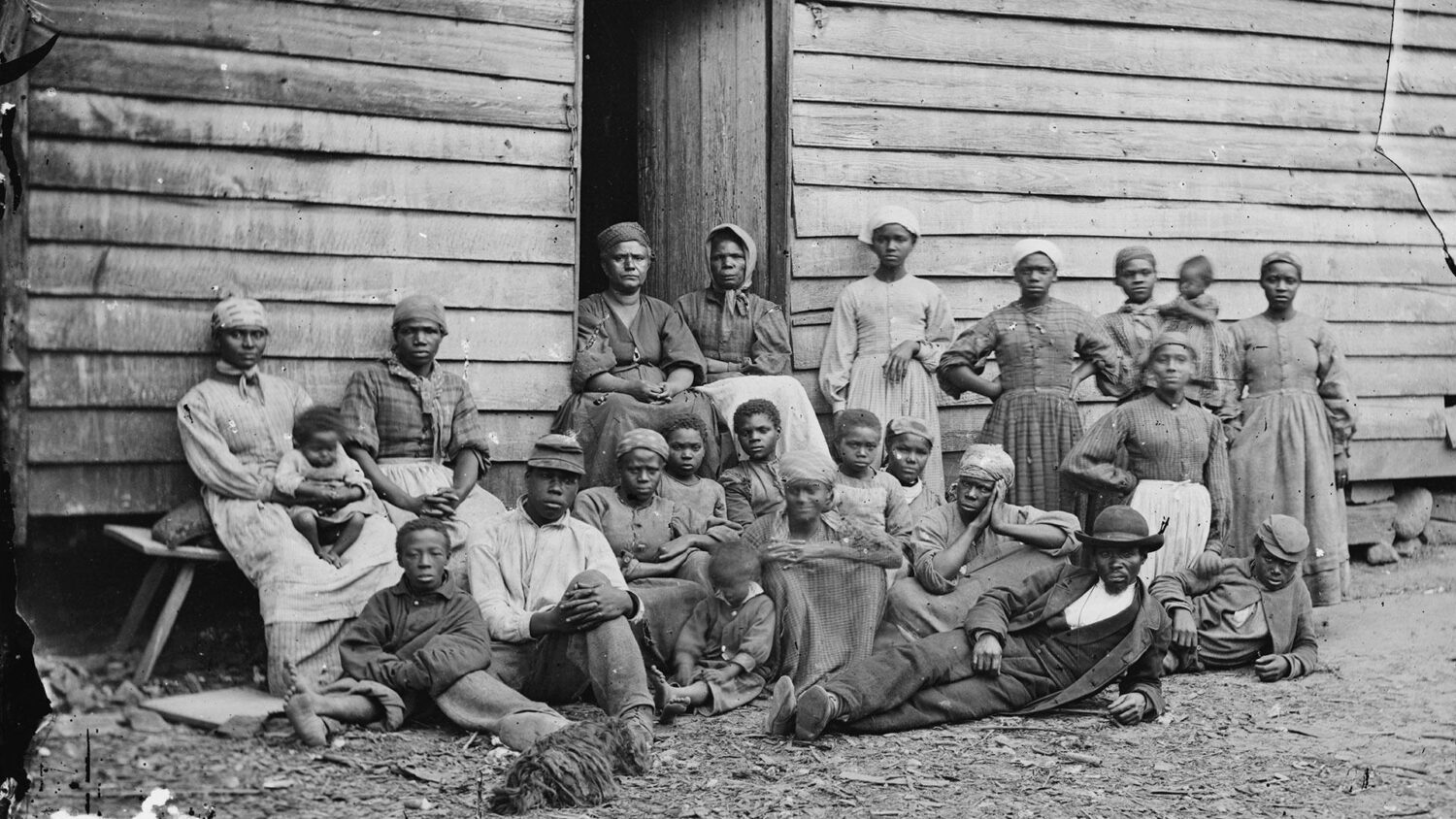

However, African Americans forced the federal government to reconsider the status of the enslaved through their own actions. As soon as it began, news of the war spread through Black communities across the South. Immediately, hundreds of African Americans escaped enslavement and fled to Union lines. This number soon rose to thousands, reaching hundreds of thousands by the end of the war.

While the federal government was not initially concerned with the status of enslaved people, runaways now in its camps forced reconsideration. These runaways’ status was unknown. The outbreak of war allowed Union officers to consider these fugitives as “contrabands of war” and refuse their return to their masters. Contraband status was not full freedom or full citizenship. They were property seized to hurt the Confederate war effort and aid the Union. However, it was the initial step towards ending slavery.

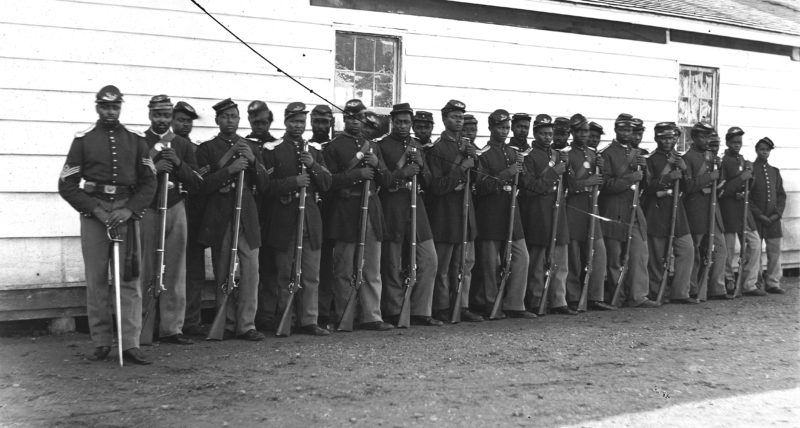

The next step was enlisting Black soldiers. As soon as the war began, many anti-Slavery advocates called for arming of Black soldiers to win the war and achieve equal citizenship. “Let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.,” Frederick Douglass said, “let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” Many Americans were resistant to this change, as racist Congressmen could not imagine Black men as effective soldiers. They claimed they were too stupid to follow orders and too cowardly to fight. Opponents knew that fighting and dying in war would bring claims of citizenship, and feared white men taking orders from “colonel Sambo.”

But the war dragged on, and the Union forces were far from winning. The Union army needed men to replace the growing number of casualties. In 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the enslaved in Southern states, stating

All persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free... And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

The Proclamation was a war measure. This meant it freed slaves only in areas of rebellion, and around 800,000 were exempted because they were in areas already controlled by the Union army or in states that allowed slavery but stayed in the Union (Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri). Still, the Proclamation made the destruction of slavery a Union war aim. The Union army was now an army of liberation.

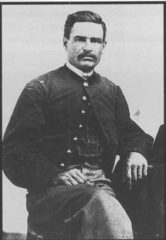

Black men from across the country began enlisting as soon as the Proclamation went into effect. Some were already in Union camps as “contraband,” and many others lived in areas exempted from the Proclamation and saw enlistment as their only way to freedom. Many more were free Black men living in the North. One such man was Stephen Swails, who left behind his wife and job as a boatman in New York to join the army, where he became the first African American to receive commission as an officer. Swails was initially refused promotion due to his “African descent.”

“What better field to claim our rights than the field of battle? Where will prejudice be so speedily overcome?” asked Robert Hamilton, a Black newspaper editor. “It is now, or never... A century may elapse before another opportunity shall be afforded for reclaiming and holding our withheld rights.” Nearly 200,000 Black men served in the Union army and navy, more than 1/5 of the nation’s eligible Black male population. 74% of free Northern Blacks of military age fought for the Union.

Lincoln and other officials initially foresaw Black troops performing non-combat duties so white troops could be used for combat action. Almost immediately, however, Black troops proved their combat ability in every part of the war. “Many persons believed... and confidently asserted, that freed slaves would not make good soldiers; they would lack courage, and could not be subjected to military discipline. Facts have shown how groundless were these apprehensions,” reported the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Lincoln, Stanton, and General Ulysses S. Grant agreed that the Black soldiers were essential in winning the war.

Black troops faced unique dangers. Their mere existence enraged Southern troops. At Fort Pillow, hundreds of Black soldiers attempted to surrender but were brutally massacred by Confederate soldiers in scenes that would predict the coming Jim Crow violence. The Confederate government did not recognize Black prisoners of war, instead calling them slaves in insurrection. This meant captured Black soldiers, including those free before the war, faced re-enslavement, torture, and execution.

Within the Union army, Black soldiers faced discrimination. Units were segregated, and Black regiments had white officers. Black soldiers received less pay and faced racism and harassment from other soldiers. Frederick Douglass pushed strongly for pay equity for the Black soldiers. Congress finally acted in 1865 to equalize the pay and offer full retroactive pay to Black soldiers.

African Americans helped the war effort outside of combat. By the end of the war, more than a hundred contraband camps contained nearly 400,000 African Americans. From the Mississippi Delta to the Sea Islands of South Carolina, Black men, women, and children worked to support the war effort. They constructed fortifications and railroads and served as cooks and nurses. Some labored on plantations to aid the Union war effort. For those still in bondage, many resisted overseers and created spy networks throughout the South.

Actions by Black folk changed the meaning of the Civil War, turning it from a war to preserve a white government into a war to destroy the institution of slavery. The victories earned during the war would be made permanent by Constitutional Amendments. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States, the 14th Amendment made African Americans full citizens, and the 15th Amendment laid the groundwork for black male suffrage.

Works Cited

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial

James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom

Louis Gerteis, From Contraband to Freedman

Louis Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment

Ira Berlin, Barbara Fields et al, ed. Free At Last: A Documentary History of the Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War

Further reading:

Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military during the Civil War, from the National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war By Elsie Freeman, Wynell

Burroughs Schamel, and Jean West. Originally published as "The Fight for Equal Rights: A Recruiting Poster for Black Soldiers in the Civil War." Social Education 56, 2 (February 1992): 118-120. [Revised and updated in 1999 by Budge Weidman.]

Jarrod Showalter is a graduate student pursuing a master's degree in Public History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His area of study is the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, with an emphasis on the era’s racial politics. His other work has covered the Jim Crow era, redlining, and the Early American Republic. He is a teaching assistant in the UWM History Department, where he teaches courses on early American history and the Holocaust. He has a bachelor’s degree in history and political science from Knox College in Galesburg, IL. Showalter is also a museum professional pursuing a graduate certificate in Museum Studies from UWM. He has worked in museums at the local, county, state, and national levels. He is originally from Ankeny, Iowa.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.