What It Was Like to Be a Black Patient in a Jim Crow Asylum

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Julia Metraux. Mother Jones

In March 1911, the segregated Crownsville asylum opened outside Baltimore, Maryland, admitting only Black patients. It was the first to house Black people in the state, but when they arrived, their main role wasn’t to get support—it was to build the asylum. The combination of ableism and sanism—harmful beliefs about the nature and treatment of mental illness—with anti-Black racism in the Jim Crow South all but ensured that Black patients were treated worse than white ones held in other asylums throughout the state.

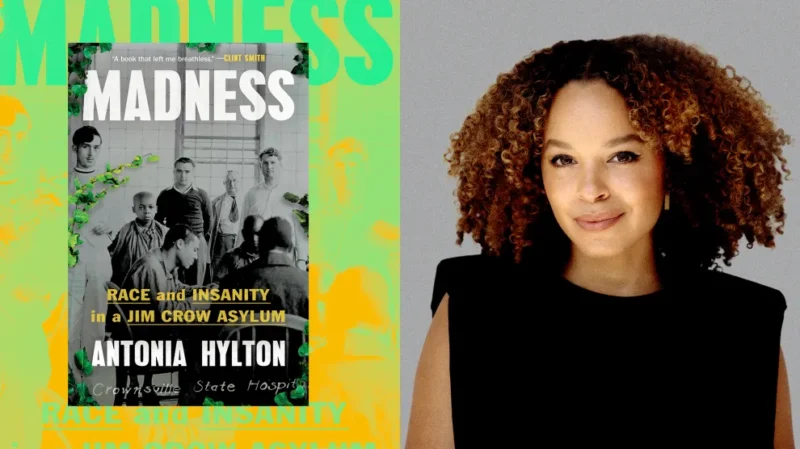

In Madness, journalist Antonia Hylton details the institution’s treatment of Black patients—some placed there due to being orphans, seeking better treatment at work, or, in the case of one British man, because some white people found his accent to be suspect. Hylton discovered Crownsville as a university student, wanting to learn more about the history and experiences of people of color in mental health systems.

When she began her research, Hylton knew that Black patients had been mistreated, but found that many records the state of Maryland was supposed to keep had been destroyed or damaged. So she weaved together what archives she could find—like reporting from Black newspapers at the time—and interviewed surviving ex-employees who remembered Crownsville before reforms started to take place.

“Starting to learn more about Crownsville and sharing my research with my own family,” Hylton told me, “opened up doors and started conversations”—including about her father’s cousin Maynard, who experienced auditory hallucinations and was killed by an Alabama police officer in 1976.

Nearly two decades after Crownsville shut down for good in 2004, Hylton talked to Mother Jones about its history, how Black people with mental illnesses have been mistreated, and why it’s crucial to end the demonization and criminalization of marginalized people who live with mental health conditions today.

Learn more about Jim Crow’s impact in our online exhibit gallery.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.