Their Palm Springs Neighborhood Burned More Than 50 Years Ago. They Want Compensation.

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By By Audra D. S. Burch, The New York Times

The Black and Latino families of Section 14, who made up much of the labor force of Palm Springs, are asking for reparations for what they say was a racially motivated attack.

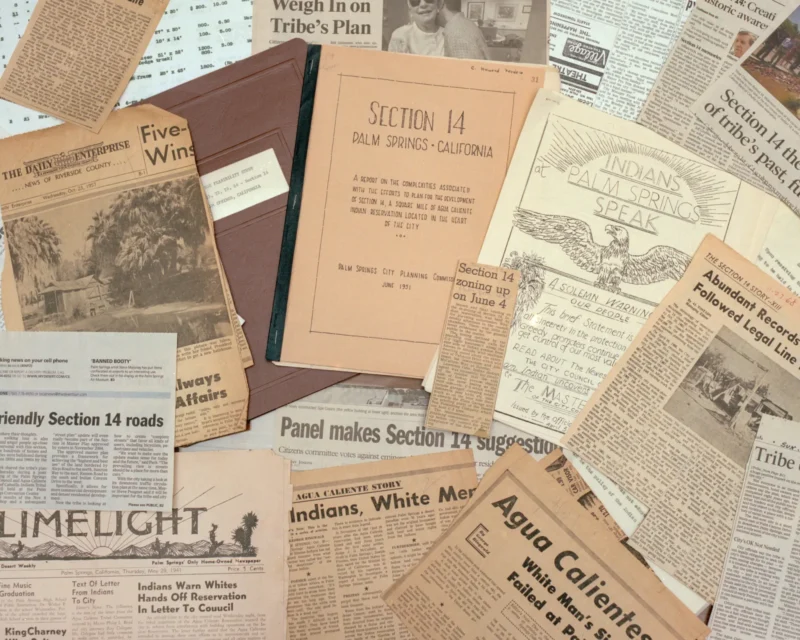

The billboards rise above the desert valley, introducing millions of visitors to what was an almost forgotten chapter in Palm Springs history. “Know before you go. Palm Springs Section 14,” one billboard reads. “We smelled the smoke, we watched our houses burn.”

In the 1960s, in Palm Springs, a sun-drenched resort destination in Southern California, a neighborhood of mostly Black and Latino families was razed to make room for commercial development. A 1968 report by the state attorney general called it “a city-engineered holocaust.”

Today, there are few physical remains of the community called Section 14 beyond a vacant lot and the remnants of concrete slab foundations that once held houses. A convention center, hotels and a casino now dominate the landscape.

The Palm Springs Section 14 Survivors group, made up of aging former residents and descendants, is asking for compensation for the loss of their homes and personal property, along with damages for racial trauma. The city apologized for its role and said it was committed to pursuing a reparations program. But negotiations stalled.

Until now.

California is at the forefront of the movement to compensate African Americans who have been harmed by systemic racism and the legacy of slavery, but the experience in Palm Springs underscores the challenges of broadening largely symbolic support to concrete actions. Last year, a state panel recommended dozens of policy changes and billions of dollars in reparations to the state’s Black residents. State lawmakers have acted on some of that guidance but have not proposed any direct cash payments.

In April, after months of intense talks, Palm Springs offered about $4.3 million for up to 145 properties to settle the claim — a tiny fraction of what the Section 14 group had proposed — along with building affordable housing and other community projects.

Areva Martin, a Los Angeles civil rights attorney representing the group, called the city’s pledge a first step in the negotiations. But she added that the offer “relies on flawed data and improper analyses.”

Find more Breaking News here.

Explore our virtual exhibit galleries here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.