In Baltimore’s Senior Homes, Overdoses Plague a Forgotten Generation

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Nick Thieme, Alissa Zhu and Jessica Gallagher from the New York Times

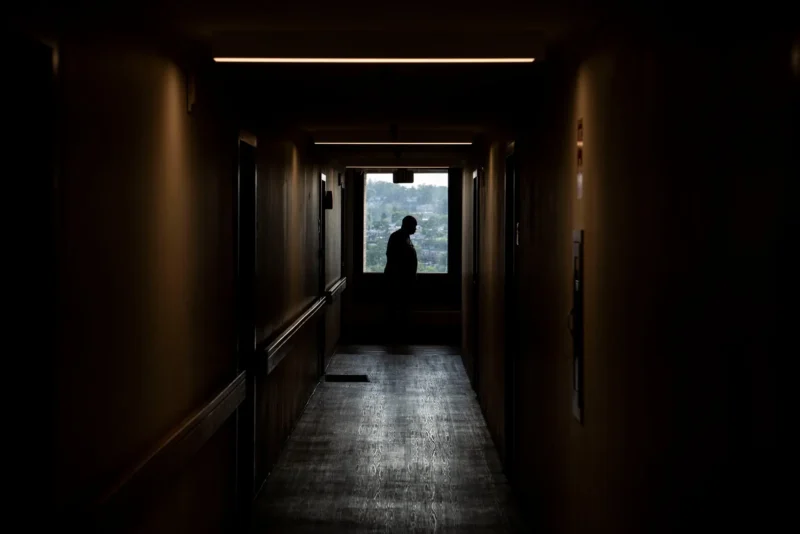

Many are dying from fentanyl and other drugs. The hardest-hit are Black men in their 50s to 70s, a group that Baltimore’s changing economy left behind.

Larnell Robinson sat at a desk in his cluttered office last September, between a bookshelf full of Bibles and a table stacked with the overdose antidote Narcan. He slid out a list of residents of the West Baltimore high-rise where he was tenant council president — one of dozens of subsidized complexes that house the city’s poor seniors. One by one, he began scratching through names, conducting a grim accounting of the dead.

William, 63, killed by fentanyl and found in his ninth-floor unit in February 2023. Richard, 61, discovered in an apartment with multiple drugs in his system two and a half weeks later. David, 68, three days after that, also dead from fentanyl.

And then 59-year-old Glenn, who had lived on Mr. Robinson’s floor for years. Known for his willingness to run errands for others, he often biked to the store to get Mr. Robinson cigarettes. But after not seeing Glenn for a day, Mr. Robinson stuck a flier in his door. When it was still there the next morning, he summoned security.

This was one death, Mr. Robinson said later, that he couldn’t bear to witness. “I feel like I work at the morgue sometimes,” he said in an interview.

Over the past six years, as Baltimore has endured one of America’s deadliest drug epidemics, overdoses have fallen surprisingly hard on one group: Black men currently in their mid-50s to early 70s. While just 7 percent of the city’s population, they account for nearly 30 percent of drug fatalities — a death rate 20 times that of the rest of the country.

Black men of that age in the city are more likely to die of overdoses than cancer or Covid at the height of the pandemic; drugs are essentially tied with heart disease for their top killer. “I can’t think of another situation like this,” said Robert Anderson, chief of statistical analysis and surveillance at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those men were part of a little-recognized lost generation, their lives shaped by forces that have animated the city’s drug crisis for decades, according to an examination by The New York Times and The Baltimore Banner.

Half a century ago, manufacturing jobs began to disappear in an industrial city where Black families had few other opportunities to build wealth. By 1980, nearly half of Baltimore’s Black men under the age of 30 were out of work — a level similar to Black unemployment during the Great Depression.

At the same time, an influx of highly addictive illegal drugs created a lucrative but corrosive shadow economy. Some young people turned to dealing drugs and then using them. Many were arrested and incarcerated, never finding jobs that let them move ahead.

Baltimore’s Black men of this generation have been dying of overdoses at some of the highest rates in the country ever since, a Times/Banner analysis found. More than 4,000 have been killed since 1993 amid waves of drugs: first heroin and crack cocaine, then prescription opioids and now fentanyl — the deadliest drug threat America has ever seen.

Find other Breaking News stories here.

Explore our virtual exhibit galleries here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.