Freedom Summer

Share

Risking Everything: The Fight for Black Voting Rights

Explore Our Galleries

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Mia Phifer

Editor: Robert S. Smith, PhD

Even though the federal government had legally mandated desegregation following the Brown vs Board of Education decision in 1954, enforcement was often left to local governments. Many of the governments in the South refused to comply with federal law and insisted on maintaining their “southern way of life.” This was code for keeping Black citizens segregated, impoverished, underemployed, and disenfranchised; separate and unequal. The consistent resistance to racial progress in the state of Mississippi during the 1960s resulted in the most violent period in the state’s history since Reconstruction. It also resulted in one of the most captivating periods in American history where thousands of brave citizens risked everything to stand up to violent oppression in order to secure the right to vote in Mississippi and across the nation.

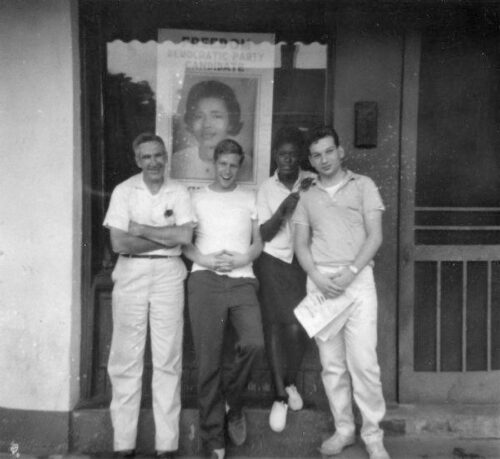

In the summer of 1964, Freedom Summer volunteers pose in front of a campaign poster for Victoria Jackson Gray, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party candidate for Congress representing the 5th District. Photo is likely taken outside of the Victoria Jackson Gray's MFDP headquarters.

In the summer of 1964, at the height of the modern Civil Rights Movement, leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized a large-scale voter registration drive. With support from Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and hundreds of northern volunteers (mostly white college students), the summer’s activities expanded far beyond just registering voters. Under a newly formed alliance called Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), the movement led to the creation of Freedom Schools, the formation of a political party, and demonstrating that through interracial cooperation change could happen, even in Mississippi.

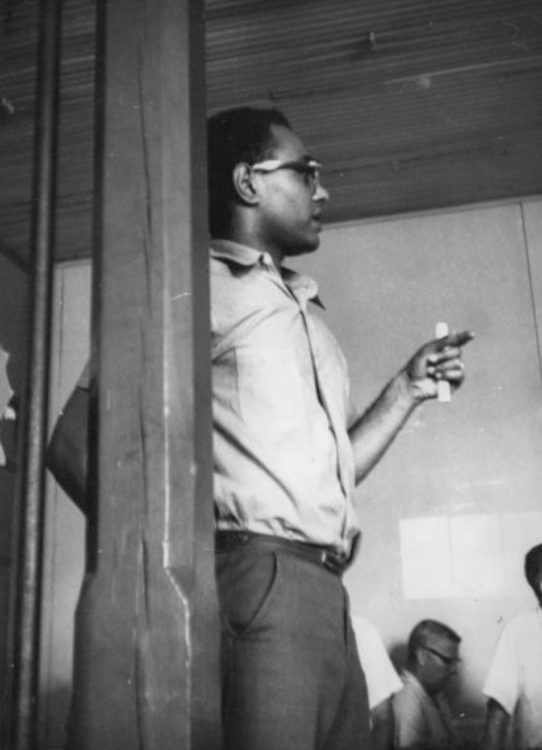

Bob (Robert) Moses speaking at the Freedom School Convention during Freedom Summer. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Although hundreds of white students traveled from the North to support Freedom Summer, the movement was intentionally led by Black activists such as Bob Moses, and Black Mississippians such as Fannie Lou Hamer. These leaders knew first hand what was at stake and the very real violence the volunteers would face in the state. They prepared the often naive white northern volunteers for this violence as best they could and trained them in the ways of nonviolent resistance. This dynamic created tense conversations between the Black leaders and the white volunteers in the months leading up to Freedom Summer, but through these training sessions a gradual sense of trust, commitment, and cohesion was created.

Once they arrived in Mississippi, volunteers were hidden and harbored by local Black communities across the state. Jackson was the heart of the operation, but in small towns across Mississippi, volunteers lived and worked with local communities to canvas neighborhoods for potential voters, set up and teach at Freedom Schools, and identify future Black leaders to sustain the movement once the summer came to an end. The leaders and volunteers of Freedom Summer, as well as the Black Mississippians who helped them, knew that a violent backlash to the movement was inevitable; they knew that the work was worth this risk.

Voter Registration

In a deeply segregated Mississippi in 1960, 42% of the state was Black but only 6% of Black Mississippians were registered to vote. Although they knew they would not succeed in registering significant numbers of voters, one of the primary goals of Freedom Summer was to enroll new voters in order to document the resistance for evidence in future federal lawsuits. They also aimed to “replace generations of fear and apathy with newfound pride and hope.”

Leading up to the summer of 1964, organizers within the Civil Rights Movement realized that direct action (such as sit-ins and boycotts) that had worked in other states would not work in Mississippi. Those that had tried this route had been met with firebombings, beatings, and assassinations. SNCC concluded that the only way to address the violent white power structure in Mississippi was through the ballot box. Through voting, Black Mississippians would be able to finally control their own lives and change local leadership.

In towns across Mississippi, the local registrar had complete control over who could register to vote, and they often wielded this control to deny Black citizens this right. Using literacy tests, poll taxes, and complicated registration forms with subjective questions, as well as the threat of violent and economic consequences, these Mississippi officials all but guaranteed Black people would be unable to register even if they tried. Retaliation was a real threat and although Black people tried to register, when they did their homes, jobs, and other types of government assistance were taken away from them. If they were successful in registering, their names were published in the paper for two weeks, resulting in direct violent threats to their lives.

Two women stand on the porch of a home. Three men, probably Freedom Summer volunteers, are talking to them. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Because of this history, the canvassing done by Freedom Summer volunteers had very little return on effort in terms of actual numbers of Black citizens registering to vote. However, the voter registration projects run by Freedom Summer volunteers in 33 towns and cities across Mississippi helped raise consciousness about the importance of voting and an abundance of legal evidence was gathered. As one training document stated, “the job of the voter registration worker is to get people to try.”

Freedom Schools

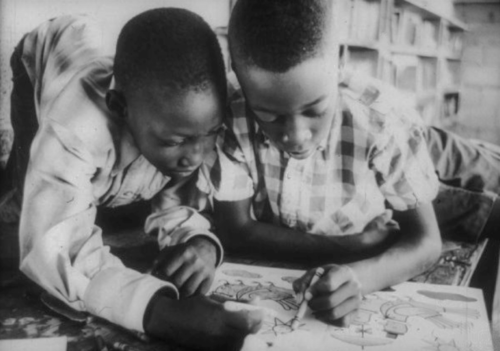

Two children color together in a coloring book during Freedom Summer. Wisconsin Historical Society.

In addition to identifying Black Mississipians and helping them register to vote, Freedom Summer volunteers dedicated a significant portion of their efforts to building and running educational centers known as Freedom Schools. Often taught in the evenings and on weekends to accommodate work schedules, these classes were held in churches or outdoors. Educators taught African American and African history, literacy, and other subjects purposefully denied to Black Mississipians in traditional schools.

Adults as well as children benefited from the lessons taught using the Freedom Summer curriculum. Since literacy tests had long been used as a form of denying Black citizens the right to vote, lessons that focused on reading and writing were of particular importance.

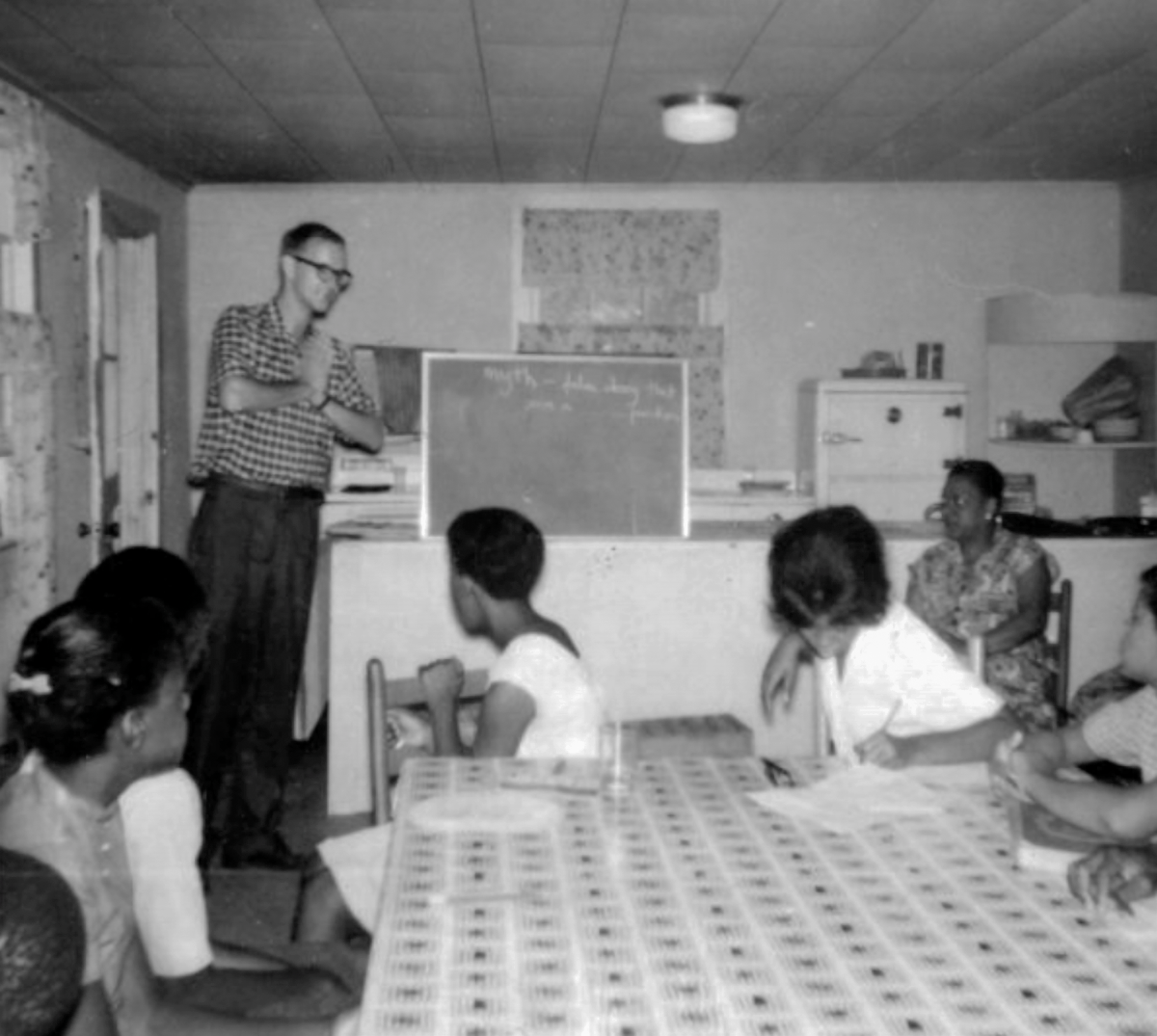

Students at Freedom School meet outdoors for class during Freedom Summer. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Although Freedom Schools were initially seen as secondary to the voter registration effort, they quickly became a central part of the movement. With this schooling, the volunteers discovered a real thirst for knowledge among the communities they were in and made a conscious effort to identify and develop future leaders during classes. The volunteers knew they would eventually have to return home (mostly to northern towns and cities), leaving the movement in the hands of Mississippians. This ended up being one of the most rewarding parts of the summer for many volunteers.

Learn more about Freedom Schools in Milwaukee at https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/keyterms/freedom-schools/ and in the Wisconsin Exhibit in this gallery.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

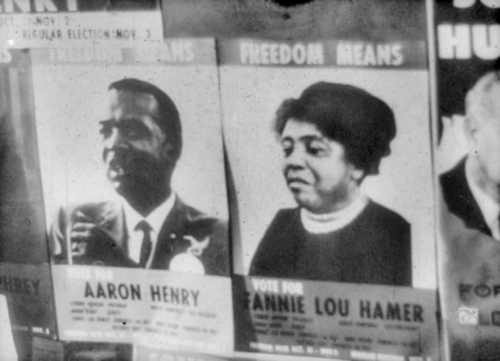

Campaign posters for two Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) candidates, Aaron Henry and Fannie Lou Hamer. Wisconsin Historical Society.

1964, the year of Freedom Summer, was a Presidential Election year, which was a conscious choice by the SNCC organizers. In addition to voter registration and Freedom Schools, the movement also involved the creation of a new political party in the state of Mississippi: the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP).

That summer, the MFDP sent their own delegation (a group of people meant to represent the state) to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. This diverse and truly representative group was meant to delegitimize the state government sanctioned all white delegation. Fighting for morality and truth in representation, the MFDP delegation set out for the DNC with the goal of unseating the other delegation, as well as drawing national media attention to the Freedom Summer cause in Mississippi.

A nighttime rally outside the Atlantic City Convention Hall in support of seating the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson purposefully intervened in the MFDP’s efforts at the DNC, thinking that it might hurt his chances at re-election if they replaced the official Mississippi delegation. He instigated an unacceptable compromise and even went as far as to call an impromptu and unnecessary press conference during which MFDP leader and delegate Fannie Lou Hamer gave what became a powerful, iconic, and historic testimonial.

A close-up of Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977), Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) candidate and noted civil rights leader. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Hamer, a Mississippi sharecropper and essential leader during Freedom Summer, brought a much-needed spirit to the movement. As a Black woman and a life-long working class Mississipian, she could speak first hand to the injustices Black people faced in the state. Her speech at the DNC detailed her experiences with violent backlash by local police when she and others had tried to register to vote in Indianola. She asked the nation, “Is this America? The land of the free and the home of the brave? Where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives are threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America?”

The MFDP delegation was not seated, but like so many other efforts of Freedom Summer, the true impact was opening the eyes of the nation to injustice and combating apathy. Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech was replayed nightly and the MFDP delegation became a symbol for what true representation in the South could look like.

Impact

Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson and prohibited racial discrimination in voting at the federal level. It abolished literacy tests and allowed for federal intervention if states and local governments were denying people the right to vote based on their skin color.

This landmark legislation got its birth in Freedom Summer. Thanks in part to the dedication of the volunteers, as well as the brave Black Mississipians who risked their lives attempting to register to vote, by 1965 60% of Black people across the country had registered to vote. It was true, as SNCC had theorized, that if the movement could crack Mississippi, they could crack the entire country.

Freedom Summer changed all the activists and volunteers forever, and showed the power of a truly interracial movement led by young people. After the nearly 1,500 volunteers returned home, they had left behind a legacy of activism and education in Mississippi, helping cultivate future leadership in the state. As of 2014, when PBS’ Freedom Summer documentary was produced, Mississippi had more Black elected officials than any other state.

Click here to view more Risking Everything: The Fight For Black Voting Rights.

Scholar-Griot, Mia Phifer is the Senior Education, Collections, & Outreach Coordinator at America’s Black Holocaust Museum. She is a trained Public Historian who earned her M.A. in History at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, along with certificates in Museum Studies and Nonprofit Management. Her expertise is in historical research & writing, collections management, curriculum development, advocacy, and educational programming. At ABHM, Mia designs and implements ABHM’s educational programs, manages the museum’s collections and archives, and initiates and sustains ongoing partnerships and collaborations locally and nationally.

Editor, Dr. Robert S. Smith is the Harry G. John Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching & Outreach at Marquette University. He serves as ABHM’s Director of Education and Resident Historian. His research and teaching interests include African American history, civil rights history, and exploring the intersections of race and law. Dr. Smith is the author of Black Liberation from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter and Race, Labor & Civil Rights; Griggs v. Duke Power and the Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Prior to joining Marquette University, Dr. Smith served as the Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Inclusion & Engagement and Director of the Cultures & Communities Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And, Rob is the proud father of Henderson Marcellus Smith.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.