Voting Rights Post Emancipation and During Jim Crow

Share

Risking Everything: The Fight for Black Voting Rights

Explore Our Galleries

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Adamali De La Cruz

Editor: Robert S. Smith, PhD

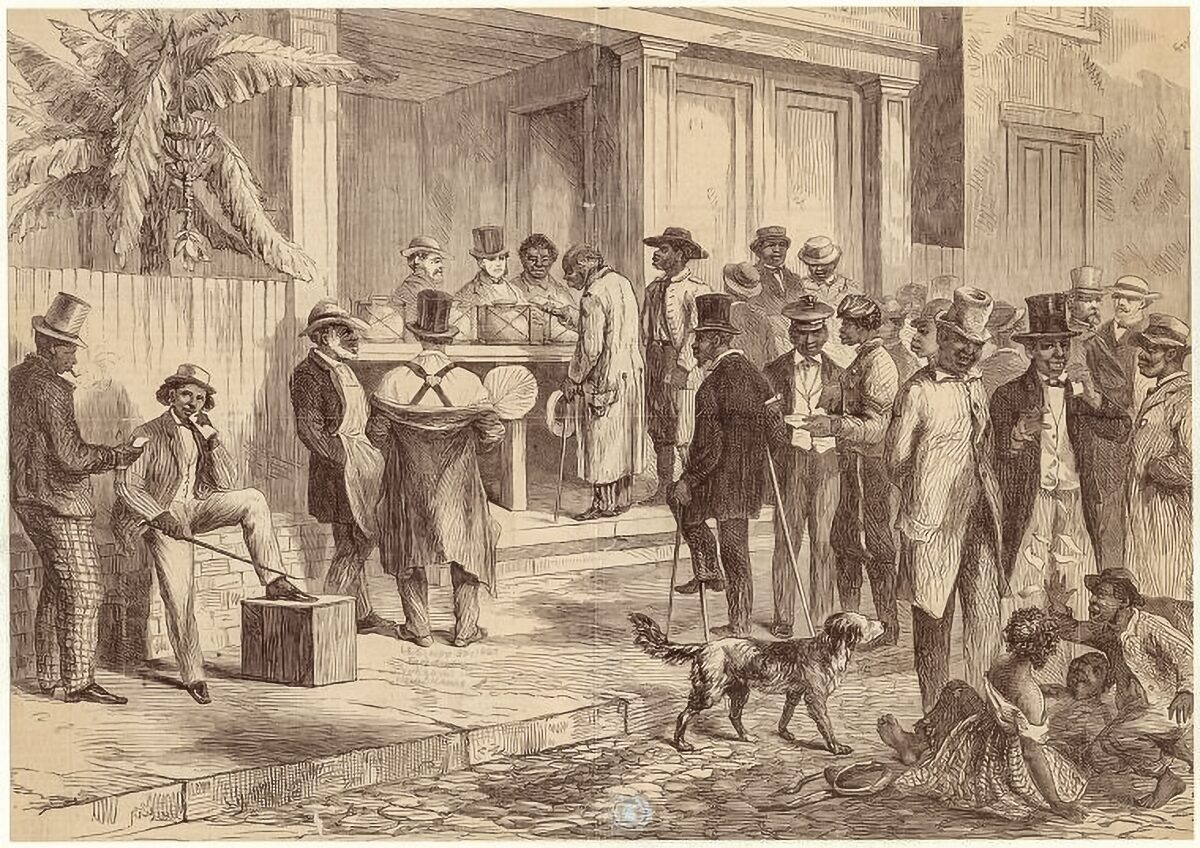

Illustration of Black men voting in New Orleans in 1867 who had just acquired the right to vote that same year through the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. Public domain.

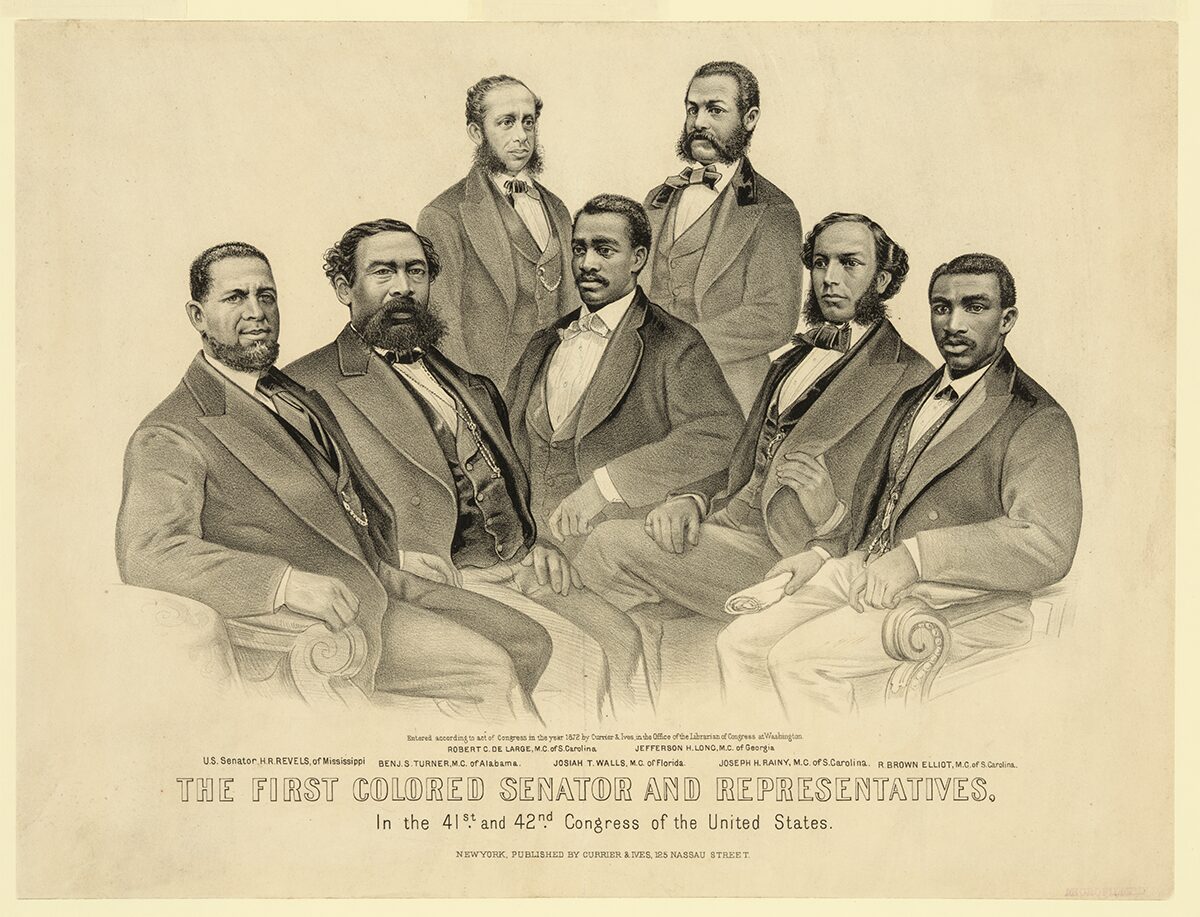

The First Colored Senator and Representatives - Many black men became elected officials not just at the local level, but at the federal level as well. Library of Congress.

Reconstruction and Voting Rights For Some

With the end of the Civil War (1861-1865), Congress was tasked with uniting the northern and southern states through the process known as Reconstruction (1865-1877). Known as Radical Reconstruction, this period welcomed the nation’s first true experience with a racial democracy. Black people actively pursued full citizenship by engaging with politics and voting almost immediately upon the ending of race-based enslavement.

For many African Americans, one of the most important rights of citizenship was voting because with it came the right to hold office and to have a direct say in their elected officials and therefore local politics. African Americans in elected offices could ensure that the voices of everyday African Americans were heard and acted upon because of shared struggles and the basic tenets of our representative democracy. Indeed, during the era of Reconstruction, over 1,500 Black men held public office in southern states.1

While the 15th Amendment protected voting rights in important ways, those constitutional protections did not extend to women, no matter their race. But make no mistake, Black women were deeply engaged with politics in ways both seen and unseen. Black women remained committed to the fight for voting rights by advocating for universal suffrage and supported Black men in their political pursuits.

Indeed, Black women continually faced a dual burden of supporting the fight against racism while also advocating for the rights of women. Black women developed strategies and organizations that sought race and gender equality in employment, education, housing, and other avenues of life.2 Meanwhile, the fight for equal voting rights continued throughout the 19th century with many Black intellectuals, men and women alike, leading the charge. Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass are a few of the noted voices who were involved in championing voting rights for all. Black women would not receive the right to vote until the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920.

'Of Course He Wants To Vote The Democratic Ticket' (October 1876), Harper's Weekly.jpg - While more often than not voter intimidation was used to prevent Black Americans from voting, this shows someone being intimidated to vote Democrat at gunpoint. Public domain.

Jim Crow and Voting Rights

With the rise of many Black elected officials such as Hiram Revels, Joseph H. Rainey, Robert C. Delarge, and Robert B. Elliott3 came a backlash of voter intimidation and violence directed at Black elected officials, politically active African Americans, and any organizations that supported Black political participation. When the US government ended its commitment to Reconstruction and removed military support for African Americans from the former Confederate states (1877), white southerners were unleashed to enact state laws and commit rampant racial violence to deny African Americans the full capacity of newly gained voting rights. White southerners began to take back control of southern governments and push out the first wave of Black politicians from local, state, and federal offices. Reconstruction and the ensuing decades of the 19th century was one of the most violent periods in American history.

Through Jim Crow laws, racial violence, and public intimidation, Black political participation declined significantly by the 1890s. Southern legislatures began to implement various methods of voter suppression tactics including poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses.4 These tactics specifically targeted poor African Americans who could not afford to pay the taxes, own land, or get an education to pass the literacy tests. Grandfather clauses were an especially flagrant violation of the 15th Amendment because a large portion of African Americans were descendants of people who had been enslaved and by definition never had voting rights. Meanwhile, white supremacists organizations such as the Klu Klux Klan used extralegal violence and intimidation to make sure that African Americans would not vote, run for office, or vocalize any opposition towards racist legislation that defined the Jim Crow Era. In fact, the Klan became active as early as 1866, just as Reconstruction began, using various forms of racial terror aimed at African Americans and their allies.5 By the emergence of Jim Crow in the 1880s/90s, the Klan had established a foothold across the South terrorizing many Black people and their families.

The active suppression and outright denial of voting rights to African Americans was one of the main causes of the Civil Rights movement. See the Freedom Summer exhibit for more information on voting rights activism.

Click here to view more Risking Everything: The Fight For Black Voting Rights.

Endnotes

1“150 Years and Counting,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Accessed September 4, 2024, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/reconstruction/voting-rights

2Megan Bailey, “Between Two Worlds: Black Women and the Fight for Voting Rights,” National Park Service, Accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/black-women-and-the-fight-for-voting-rights.htm

3https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/african-americans-house-of-reps/

4https://www.abhmuseum.org/voting-rights-for-blacks-and-poor-whites-in-the-jim-crow-south/

5Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction, (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), “Chapter 6: The Facts of Reconstruction,” epub.

Scholar-Griot, Adamali De La Cruz is the Education and Griot Coordinator at America’s Black Holocaust Museum. She is a graduate of Marquette University's History department with a focus on medieval studies. She joined ABHM as a Griot/Center for Urban Research and Teaching Outreach (CURTO) Intern in 2022 and formally joined the ABHM Ed. Dept in 2023. As the Education and Griot Coordinator, Adamali has developed the Junior Griot Program for high school students, coordinates with volunteers, has assisted in formalizing the college internship program at ABHM, and writing of virtual exhibits and other public history projects that ABHM contributes to.

Editor, Dr. Robert S. Smith is the Harry G. John Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching & Outreach at Marquette University. He serves as ABHM’s Director of Education and Resident Historian. His research and teaching interests include African American history, civil rights history, and exploring the intersections of race and law. Dr. Smith is the author of Black Liberation from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter and Race, Labor & Civil Rights; Griggs v. Duke Power and the Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Prior to joining Marquette University, Dr. Smith served as the Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Inclusion & Engagement and Director of the Cultures & Communities Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And, Rob is the proud father of Henderson Marcellus Smith.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.