Norris Dendy

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Newest Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Murdered in: Clinton, South Carolina | July 4, 1933

Norris Dendy was just 33 when he was lynched. This was not the first time that the Dendy family dealt with racial terrorizing, however. Previously, Norris' father received a threatening letter after building his family a large home outside of the part of town that housed most Black communities. The writer threatened Norris' life if his father didn't "stay in his place." By sending all of his children to college, the elder Dendy encouraged his family to become educated. At one point, the family was described as "the most prominent colored family in Clinton," and this continued to anger white residents.

Just three years before his lynching, Norris Dendy was arrested for buying stolen goods. However, the NAACP maintained Dendy's innocence, stating that he was framed. Eventually, the conviction was overturned because there was no evidence that Dendy was aware that the goods were stolen.

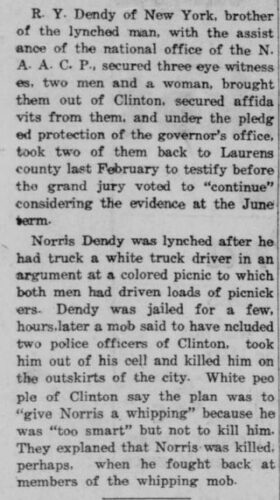

Norris Dendy's freedom--and life--would last only a few more years. In 1933, the father of five spent Independence Day driving picnickers to Lake Murray. However, he became involved in an argument with a white driver named Marvin Lollis, sometimes named "Louis" in the press, over whose truck was faster. Dendy allegedly hit Lollis after the man insulted him. Although Dendy tried to go home, he was arrested for the assault by police who may have been alerted to his location by Lollis or his friends.

Mr. Dendy was taken to the Clinton jail, where he should have remained until a trial. However, when his wife, mother, and children came to visit him that night, Deny was surrounded by a mob of men, which included officers of the law according to witnesses. One of those man fired a pistol and ordered the Dendy family to leave so that the mob could break into Dendy's cell and drag him out. The mob forced their prisoner into a car, and when his mother came near, they hit her before driving off.

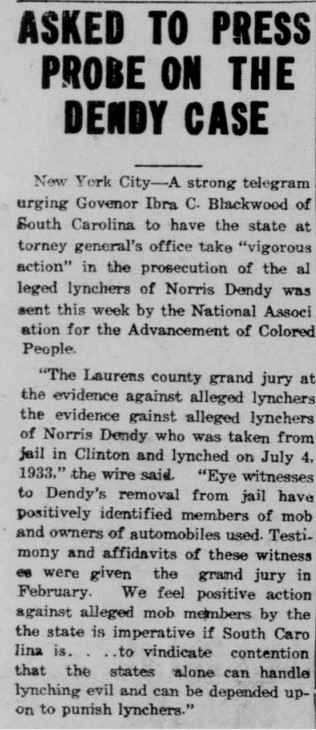

Norris Dendy was never seen alive again. His body was found in a nearby cemetery the next morning, and an autopsy revealed he has been beaten, strangled, and tied with a strong rope. An investigation began, but like so many similar cases, there was little hope that the legal system would take Dendy's lynching seriously. South Carolina's Governor Blackwood said at the time that the "[c]ase is of such a nature it can best be investigated and developed quietly."

The Dendy family, who was not happy with the detective work, reached out to the NAACP to hire their own investigator. Norris' older brother Robert Dendy was especially vigilant about pursuing charges. However, this was only possible because the family was prosperous and could afford to pay for the investigation. The result of this investigation was that five men of the 100-man mob were arrested for their part in Dendy's lynching, including Marvin Lollis. However, no trial happened because they were not indicted.

Although the NAACP continued working on the case into 1935, Robert Dendy eventually asked them to withdraw because there was little progress. The Dendy family believed the NAACP had been apathetic in their investigation and pursuit of the legal case. When the criminal case failed, a civil suit against Laurens County began. While Norris Dendy's father gave the county a chance to settle out of court, they refused, and he proceed with his lawsuit. Justice once against eluded Norris Dendy and his family after the lawyer handling their civil case died in 1936.

Even though the civil suit appears to have been dropped after the Dendy's lawyer's passing, it prompted a new anti-lynching law in South Carolina. This law allows a legal representative, such as a family member, of a lynching victim to sue the county where the lynching took place for financial damages.

The Dendy family continued to honor Norris by creating an archive of materials about his lynching, which they gave to Presbyterian College. The Dendys also helped others attend college by creating a scholarship in the name of Norris' parents.

In 2009, Norris' son Young described his life after his father's lynching to a student of San Jose State University. Young remembered a long trip in Washington, D.C. with his mother and avoiding the mill community in Clinton after they returned home. At that time, Young and his brother Norris Jr. went to live with their strict aunt. They learned to play piano and even performed in Chicago before entering school age.

Norris Jr.'s daughter describes him as an intelligent and gentle man who married and joined the military. It is likely that his family's hard work and dedication to education set him up to become a distinguished officer and, later, a professor of military science at Virginia State University. For his efforts, Norris Jr. was recognized by the Department of Veteran Affairs after he passed in 2024, continuing the Dendy tradition of excellence spearheaded by his grandfather.

Sources and Further Reading

White Mob Lynches Norris Dendy and Leaves His Body in a Churchyard