This Date In History: The Colfax Massacre Occurs

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From the African American Registry

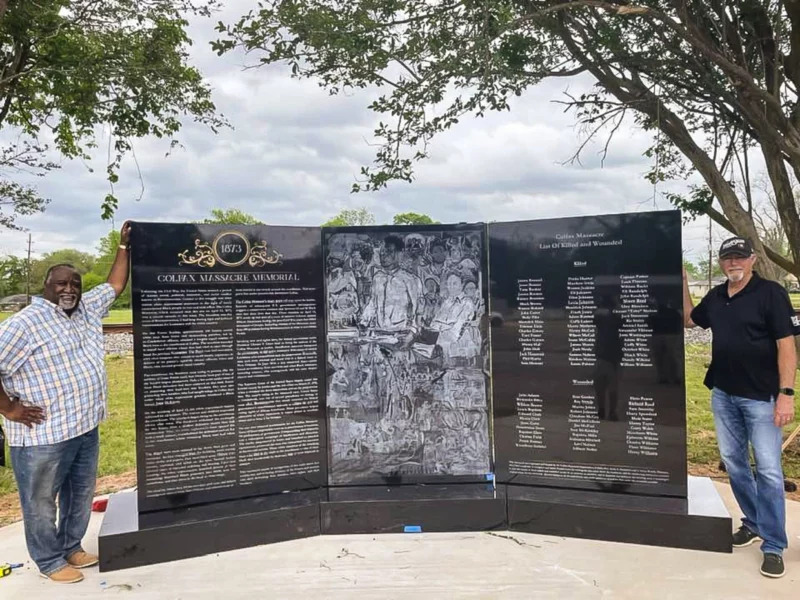

On this date in 1873, the Colfax Massacre, also known as the Colfax Riot, occurred. The violence erupted in Grant Parish Courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana.

This was when the White League, a paramilitary group intent on securing white rule in Louisiana, clashed with Louisiana’s almost all-Black state militia on Easter Sunday that year. The resulting death toll was staggering. Only three members of the White League died. But 150 Black men were killed in the encounter. Nearly half were murdered in cold blood after they had already surrendered. The incident again showed President Ulysses S. Grant how hard it would be to guarantee blacks’ rights and safety in the South.

After the end of the American Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations had been growing in strength in the South. Before the war, white Southern Democrats had enjoyed much governmental power. But when the war ended, Democrats were no longer powerful. Northern Republicans controlled the nation’s government. They placed federal troops in Southern cities to keep that control. Southerners deeply resented this imposition.

Two laws that Southern Democrats hated were the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to Blacks and declared that no state was to deprive them of “life, liberty, or property.” The Fifteenth Amendment prevented a state from denying the vote to anyone because of race. Together, these laws guaranteed Blacks equal citizenship.

Southern Democrats, however, feared that Blacks would not only vote Republican but would be considered equal to their White former masters. Conflicts between Republicans and Democrats in Louisiana were persistent in 1872. That year, the state election produced two governors claiming to be the legitimate ones. When the federal government supported the Republican governor by sending federal troops to Louisiana, the state’s white residents refused to cooperate.

Louisiana whites formed their own “shadow” government and their army, the White League. While the worst violence occurred in Colfax, other incidents were sparked in Coushatta, when the White League murdered six Republicans, and New Orleans, where 30 were killed and 100 more wounded. President Grant ordered federal troops to restore order in response to these incidents and others throughout the South. But most of the relief was temporary.

After Colfax, the federal government convicted only three whites for the murders. Ultimately, they were freed when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that they had been unconstitutionally convicted. The battle over Reconstruction and the rights of Blacks continued into the Civil Rights movement of the 20th Century and the resulting enforcement of those Civil Rights Acts into the 21st Century.

Check out the original article.

Our virtual exhibits tell tales of Black history.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.