Happy Birthday, Reverend John Rankin, Dedicated Abolitionist!

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From Wikipedia

John Rankin (February 5, 1793 – March 18, 1886) was an American Presbyterian minister, educator and abolitionist.

Upon moving to Ripley, Ohio in 1822, he became known as one of Ohio’s first and most active “conductors” on the Underground Railroad. Prominent pre-Civil War abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe were influenced by Rankin’s writings and work in the anti-slavery movement.

When Beecher was asked after the end of the Civil War, “Who abolished slavery?,” she answered, “Reverend John Rankin and his sons did.”

Rankin was born at Dandridge, Jefferson County, Tennessee, and raised in a strict Calvinist home. Beginning at the age of eight, his view of the world and his religious faith were deeply affected by two things — the revivals of the Second Great Awakening that were sweeping through the Appalachian region, and the incipient slave rebellion led by Gabriel Prosser in 1800.

[D]espite Tennessee’s status as a slave state, he summoned the courage to speak against “all forms of oppression” and then, specifically, slavery. He was shocked when his elders responded by telling him that he should consider leaving Tennessee if he intended ever to oppose slavery from the pulpit again. He knew that his faith would not allow him to keep his views to himself, so he decided to move his family to the town of Ripley across the Ohio River in the free state of Ohio, where he had heard from family members that a number of anti-slavery Virginians had settled….On the night of December 31, 1821, he rowed his family across the icy river….

During the Rankins’ first few months there, hecklers and protesters often followed the new preacher through town and gathered outside his cabin while their first permanent home was being built just yards from the river at 220 Front Street. When the local newspaper began publishing his letters to his brother on the topic of slavery (see next section), Rankin’s reputation grew among both supporters and opponents of the anti-slavery movement. Slave owners and hunters often viewed him as their prime suspect and appeared at his door at all hours demanding information about fugitives. Soon, Rankin realized that the home was too accessible a place for him to properly raise his family.

In 1829, Rankin moved his wife and nine children (of an eventual total of thirteen) to a house at the top of a 540-foot-high hill that provided a wide view of the village, the River and the Kentucky shoreline, as well as farmland and fruit groves that could provide sources of income. From there the family could raise a lantern on a flagpole to signal fleeing slaves in Kentucky when it was safe for them to cross the Ohio River. Rankin also constructed a staircase leading up the hill to the house for slaves to climb up to safety on their way further north. For over forty years leading up to the Civil War, many of the 2000 slaves who escaped to freedom through Ripley stayed at the family’s home, and none was ever recaptured there. It became known as the Rankin House and is now a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

During a visit by Rankin to Lane Theological Seminary to see one of his sons, he told Professor Calvin Stowe the story of a woman the Rankins had housed in 1838 after she escaped by crossing the frozen Ohio River with her child in her arms. Stowe’s wife (Harriet Beecher Stowe) also heard the account and later modeled the character Eliza in her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin after the woman.

The film, “Brothers of the Borderland,” is a permanent feature of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati that depicts Rankin’s work in the Underground Railroad in Ripley.

Early in his time in Ripley, Rankin learned that his brother Thomas, a merchant in Augusta County, Virginia, had bought slaves.

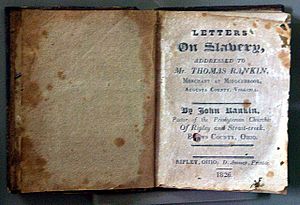

He was provoked to write a series of anti-slavery letters to his brother that were published by the editor of the local Ripley newspaper The Castigator. When the letters were published in book form in 1826 as Letters on Slavery, they provided one of the first clearly articulated anti-slavery views printed west of the Appalachians. Thomas Rankin, convinced by his brother’s words, moved to Ohio in 1827 and freed his slaves.

Read the full article here.

Read more Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

I’m very proud to be a direct desendent of John Rankin…he is my Great Great Great Great Grandfather.

I am a black who am a christian and have had the pleasure of being introduced to the story of John Rankin by a dear white sister of mine.It has changed my life.Every chance i get I visit the home and take others with me.I cannot talk about black history without sharing how the people of the underground railroad,black and white fought for the freedom of the slave

Thank you for this article. I am a relative of Jean Gilfillen Lowry Rankin. It is a blessing to see from whence my rich Christian heritage flowed. I have been to the Rankin house while it was being renovated and was moved to see where history was made and that our family was of strong conviction. Thank you ABHM for creating a website that repairs the breach in our humanity.