New York Is Cataloging, and Returning, Bloody Relics of 1971 Attica Assault

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Sam Roberts, New York Times

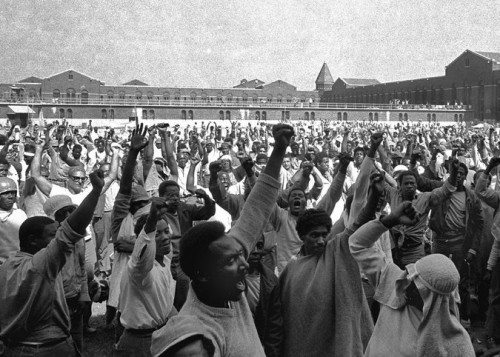

Forty-three years later, it remains a grisly benchmark: Aside from the Indian massacres of the late 19th century and an infamous 1921 race riot in Tulsa, the State Police assault that quelled the four-day uprising at Attica prison in upstate New York in 1971 was, investigators concluded, “the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

When it ended, 10 correction officers and civilian employees and 33 prisoners were dead — all but one guard and three inmates killed in what a prosecutor branded a wanton “turkey shoot” by state troopers.

Prosecutions stemming from the uprising were resolved long ago; scores of inmates and one state trooper were charged. Civil suits by relatives of the dead and injured were settled (the state paid $12 million, including legal fees, to families of the inmates, and another $12 million to families of prison employees).

But even after more than four decades, the scars have never healed.

This year, state officials finally began cataloging the bloodstained uniforms of both guards and inmates, barrels of baseball bats, a homemade cannon, makeshift knives and other ephemera that had been stored in a Quonset hut to determine which were personal belongings that could be returned to the victims’ families, and which other artifacts to ultimately discard or to retain for research or eventual display in the New York State Museum.

In August, property belonging to 12 state employees was identified. Their families were invited privately to Attica on Sept. 13, before the solemn annual public memorial service held to mark the end of the siege.

Eleven of the families accepted the state’s invitation. All but one left with some memento — a bloody or bullet-ridden uniform, a wallet, keys, a thermos, a cap — that the state Department of Correctional Services could establish as having belonged either to an individual or to an unknown colleague. The twelfth family was still considering the state’s offer.

“It was a shock,” recalled Vickie Menz, who discovered a package of personal items belonging to her father, Arthur J. Smith, when she returned to the prison for the memorial. “There was a box of my father’s things, the clothing that he was wearing for the five days he was a hostage. The pants were caked with mud. They hadn’t been laundered.”

Read full article here.

ABHM’s online exhibits detail more Black history.

Read more Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.