Discovering Family Roots in Brooklyn Slavery

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Jennifer Schuessler, New York Times

“Trace/s,” an exhibition at the Center for Brooklyn History, highlights the borough’s neglected story of slavery — and the Black genealogists helping to unearth it.

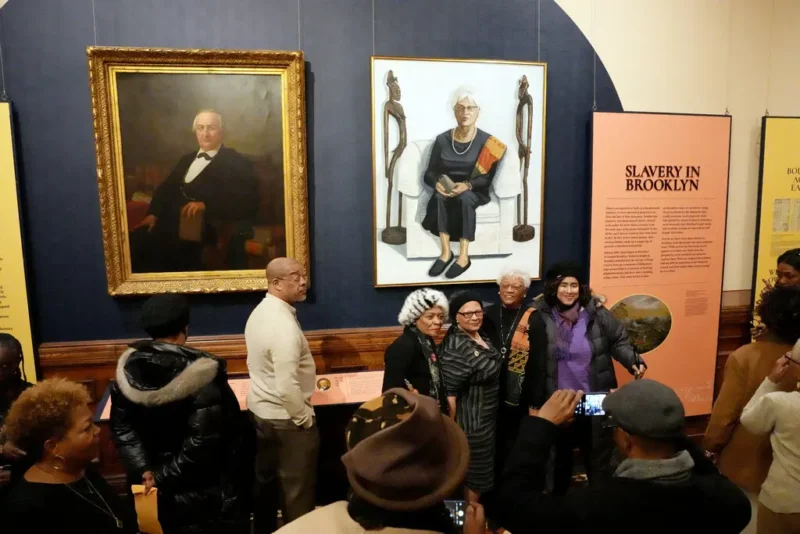

Come to the Center for Brooklyn History’s grand Romanesque Revival building in Brooklyn Heights looking for staid portraits of 19th-century burghers, and you’ll find them.

But on a recent evening, Mildred Jones, an 87-year-old retired schoolteacher born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, was pondering a less expected large-scale oil portrait — of herself.

It was hanging alongside the image of John A. Lott, a prominent judge whose family had enslaved her great-great-grandfather Samuel Anderson. Her thoughts on the likeness? Jones paused, looking a bit sheepish, then smiled.

“I just love the whole idea,” she said. “It has opened up a whole new set of information and possibilities for telling the story of Black folks in Brooklyn. We’ve been here a long time. And it’s a story that needs to be told.”

The twinned portraits of Lott and Jones are the anchors of “Trace/s: Family History Research and the Legacy of Slavery in Brooklyn,” a new exhibition looking at the borough’s long-neglected history of slavery — and the work ordinary people have done to help recover it.

The show, on view until August, draws on fresh research in the collections amassed at the center (formerly the Brooklyn Historical Society) since its founding in 1863 by men like Lott. But it also builds on the dogged efforts of amateur genealogists and family historians to track down people whose lives may have been only fleetingly recorded.

Dominique Jean-Louis, the center’s chief historian, said the exhibition helps illuminate — and begin to repair — one of the cruelest realities of slavery: that enslaved people had no right to keep their families intact.

The New York Times has more details.

Learn more about the realities of slavery.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.