Early African Women: Hunters, Warriors & Rulers

Share

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Rebecca Allyson Schnabel, M.S.

copy editors: Adrianna Ray, BA and Fran Kaplan, EdD

photo editor: Adrianna Ray, BA

"Maternal lineage" means "to descend from women." In most European societies, "paternal lineage" is what matters. Male leaders are the most honored. In the histories of many African societies, however, maternal lineage has played an important role. Some African traditions placed women in positions of power and honor, as warriors, big game hunters, rulers, and religious leaders.

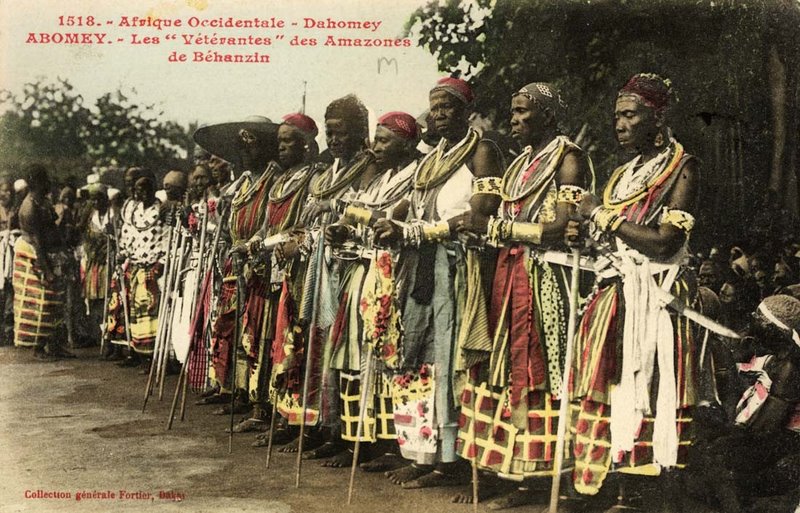

Veteran "Amazons" celebrate in the West African country of Dahomey. (Credit: Edmond Fortier)

African “Amazons”: Dahomey’s Warriors

Mbeto or Mino warriors of Dahomey. (Credit: Chris Hellier/Getty Images)

Dahomey’s female troops – the Mino – were fierce, loyal, and deadly soldiers. Unlike other female guards, they did not serve as decoration; they were an active force to be feared. Evidence suggests that most women were not equal to men in this society. These women warriors, however, were considered to be men after making their first kill. These female soldiers were formally married to the king, but remained virgins.

Dahomey was a major slaving port on the West Coast of Africa. During the Atlantic Slave Trade, the number of men there declined. Therefore, women took over male roles when necessary as hunters and warriors.

In the 17th century, female hunters called Gbeto lived in Dahomey. These women were known for hunting large groups of elephants. Eventually, these hunters became military units. Renamed the Mino (meaning “Our Mothers”), these women were trained to kill. These women impressed and terrified European powers through the centuries. The Mino lived comfortably. They were kept well supplied with rewards like tobacco and slaves. When walking the streets, men would move out of their way. To touch the Mino meant certain death.

The Mino were defeated by colonial France in the late 1800s. Dahomey was then combined with the country of Benin. The “Amazonian” warriors known as the Mino were disbanded at this time. However, some are believed to have survived into the late 1970s. Those who did, lived to see their country gain

independence from European rule.

Kandake Amanirenas of the Merotic-Kush Empire

Kandake Amanirenas ruled the Merotic-Kush Empire in what is now a part of southern Egypt and northern Sudan. She lived from approximately 50 BC - 10 BC. Kandake or Candace means “great woman,” referring to a queen or queen mother.

Kandake Amanirenas is known for fighting against the Roman Empire. She is one of several Kandake to rule Kush. She began to rule after her husband died in battle. She ruled with her son, Prince Akinidad.

In 30 BC, the Romans invaded the Kush Empire leading to five years of war. The Kushites bravely defended their home. Losing an eye in battle, she was called the one-eyed Kandake by the enemy. Overall, the defense campaign was extremely successful against the Romans. Kandake Amanirenas buried a statue of the Roman Emperor Augustus under the entrance to a temple. This was an insult to her enemy, as all who entered would step upon his face. The same year Prince Akinidad died in battle.

Nevertheless, Amanirenas refused to give up. She fought the Romans until they agreed to a peace treaty, “spar[ing] her people centuries of domination...Unlike other kingdoms on the edge of Roman Europe, Kush never was forced to pay tribute or contribute material resources to Rome.” Kandake Amanirenas is not only a marvel as a woman, but also as a warrior and leader of her time.

Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba

A portrait of Queen Nzinga that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London, England. (Credit: National Portrait Gallery)

Queen Ana Nzinga (1583-1663), of what is now Angola, is one example of an African ruler who was not afraid of European invaders. Her ancestors worked to appease the Portuguese. They traded with early colonists, exchanging enslaved people for goods. As the Portuguese made more demands, Queen Nzinga’s father began to fight back. He refused to give the Europeans more land, resources, or power.

Nzinga was her father’s first-born child. However, her mother was not the future Queen of the region. Her mother was an outsider, a formerly enslaved person who had been freed. Due to this, she was never meant to rule as Queen. Nzinga’s father trained her as a warrior and intellectual. After his death, Nzinga communicated with Portugal for her brother, who ruled their home in Africa. She got the Portuguese to come to peaceful terms with her and her people. Unable to remove them completely, Nzinga made an agreement keeping local power and minimal foreign intervention.

Upon her return home, Nzinga’s brother died, leaving the throne to her. Queen Nzinga continued working with the Portuguese but rejected their proposed peace deal. Queen Nzinga spent 40 years fighting for her people against the Portuguese. She is remembered as an inspiring military leader. Queen Nzinga also had ties to other European powers such as the Dutch. She got fleeing Portuguese soldiers and African tribes to fight against the Portuguese. Living into her 80s, Queen Nzinga never surrendered her power. She is one African leader who fought colonialization and slavery.

For further details about Queen Nzinga’s life and other reference material please check out The History Chick’s Podcast. http://thehistorychicks.com/episode-80-queen-nzinga/

Sources and Further Reading

Chigozie, Emeka. “5 Most Powerful African Queens From History.” Answers Africa. April 18, 2018. answersafrica.com/5-powerful-african-queens-history.html.

Cooney, Kara. “Women in Power-A Lesson From Cleopatra, Nefertiti and Others.” Time. October 18, 2018. time.com/5425216/ancient-egypt-women-in-power-today/.

Dash, Mike. “Dahomey's Women Warriors.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. September 23, 2011. www.smithsonianmag.com/history/dahomeys-women-warriors-88286072/.

“Episode 80: Queen Nzinga.” The History Chicks, 14 Jan. 2019, thehistorychicks.com/episode-80-queen-nzinga/.

Fikes, Robert. “Kandake Amanirenas (?-10 BC).” Black Past. May 22, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/kandake-amanirenas-10-bc/.

Johnson, Elizabeth Ofosuah. “African Princesses and Queens Exiled for Fearlessly Resisting Colonial Oppression.” Face2Face Africa. October 19, 2018. face2faceafrica.com/article/african-princesses-and-queens-exiled-for-fearlessly-resisting-colonial-oppression.

Lewis, Jone Johnson. “Queens, Empresses, and Pharaohs: Women Rulers of the Ancient World.” ThoughtCo. March 24, 2019. www.thoughtco.com/ancient-women-rulers-3528391.

Mark, Joshua J. “The Kingdom of Kush.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. February 6, 2018. www.ancient.eu/Kush/.

McKissack, Patricia C. Nzingha: Warrior Queen of Matamba, Angola, Africa, 1595. September 1, 2000. [Editor's note: A great read for students Grades 5 through 8.]

Moore, A. “10 Fearless Black Female Warriors Throughout History.” Atlanta Black Star. October 29, 2013. atlantablackstar.com/2013/10/29/10-fearless-black-female-warriors-throughout-history/6/.

“Pyramids of the Kingdom of Kush - Map - HeritageDaily - Archaeology News.” HeritageDaily. January 2020. www.heritagedaily.com/2018/02/pyramids-kingdom-kush/118369.

Sasik, Annika. “Ancient Kush.” Weebly. 2013. https://sasikexplores.weebly.com/where-and-what-is-kush.html.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Historic Kingdom of Dahomey.” Encyclopedia Britannica. May 30, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/place/Dahomey-historical-kingdom-Africa/media/1/149772/202415.

West, Racquel. “Yaa Asantewaa (Mid-1800s-1921).” Black Past. February 8, 2019. www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/yaa-asantewaa-mid-1800s-1921/.

Winters, Clyde. “Prince Akinidad of Kush and the One Eyed Kandake in the Meroite-Roman War.” Ancient Origins. October 21, 2016. www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/prince-akinidad-kush-and-one-eyed-kandake-meroite-roman-war-006854.

“Women in African History.” UNESCO Women in Africa History | Women. 2019, en.unesco.org/womeninafrica/.

Rebecca Schnabel is a graduate of UW-Milwaukee’s Masters of Public History and Museum Studies Certificate programs. She strives to cultivate a sense of community through engaging endeavors that connect history with the present, particularly through empowering the general public to apply their own agency while exploring exhibitions on social justice. Rebecca’s passion does not reside in one specific historical era or geographic location, but instead in illuminating underrepresented histories. Her specialties include interpretation, collections management, and exhibit design.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.