Founding the New Free Black Community

Share

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Jarrod Showalter, M.A.

The Civil War and the 13th Amendment to the Constitution put an end to legal chattel slavery in the United States in 1865. A chattel slave is an enslaved person who is owned forever and whose children and children's children are automatically enslaved. Chattel slaves are individuals treated as property to be bought and sold.

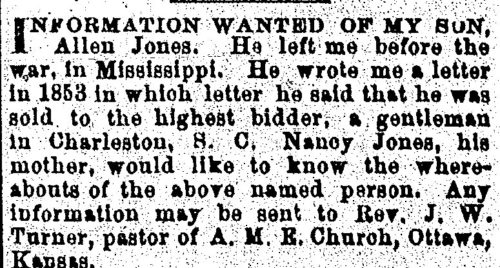

In 1886, Nancy Jones placed an ad seeking her son, Allen, in an ad in The Christian Recorder of Philadelphia.

Millions of freed Black Americans began to build their own communities across the South after the Civil War. They hoped to establish a life of freedom and prosperity for themselves and future generations.

Hawkins Wilson was one such newly freed man. Wilson was a leader in the rising Black community in Galveston, Texas. In 1867 he wrote to the Freedman’s Bureau, a government agency created to assist ex-slaves like himself: “I am anxious to learn about my sisters, from whom I have been separated many years.” He hoped that the Freedman’s Bureau could help him locate his sisters and other family. Wilson enclosed letters to be given to his sisters. He had been separated from them for twenty-four years. “Dear Sister Jane,” one began, “your little brother Hawkins is trying to find out where you are and where his poor old mother is. Let me know and I will come to see you.”

For Mr. Wilson and millions of others, freedom meant more than an end to slavery. Freedom meant the hope of setting up and managing their own communities and families. In addition, new Black institutions like schools and churches gave purpose and meaning to their freedom.

The Family

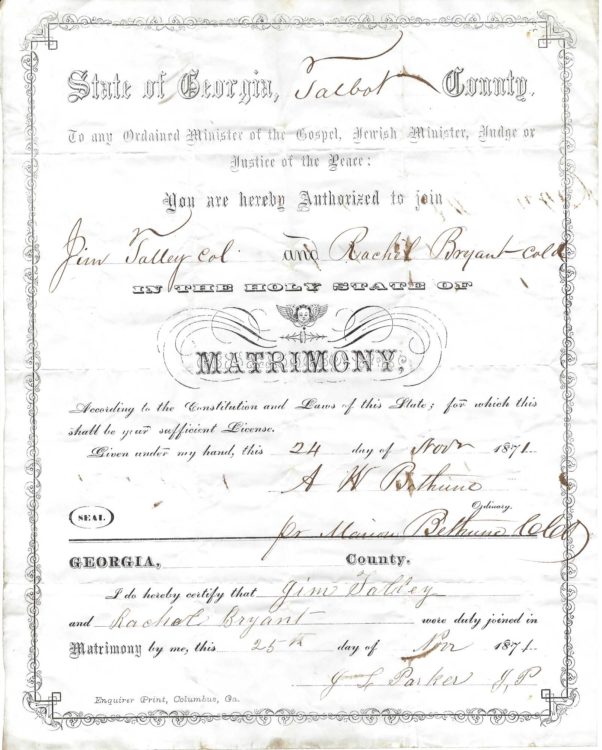

This couple, Jim Talley and Rachel Bryant, likely recently freed from enslavement, were able to formally marry in Georgia's Talbot County on May 25, 1871. This original certificate is in the collection of America's Black Holocaust Museum.

The family was a foundation of enslaved communities. Despite violence from slaveowners, the family was essential to resisting the dehumanization of slavery. Slavers had no regard for family relations. They separated husbands and wives and sold children to faraway places. Still, families persisted, creating a community and passing on cultural values from generation to generation.

After slavery’s end, one of the first things the formerly enslaved did was search for their family members. People like Hawkins Wilson looked across the country for family: “I am writing to you tonight, my dear sister, with my Bible in my hand praying... you and me to meet again. Thank God that now we are not sold and torn away from each other as we used to be.” Free men and women wrote to the Freedmen’s Bureau, purchased advertisements in newspapers, and set out on foot to find their family they had lost. Many, like Wilson, never found their loved ones.

Black families, new and old, worked for a better life during Reconstruction. They hoped an end to slavery meant the end to interference from whites into their family life. Parents now had legal control of their children and could raise them however they wanted. Before, any children of an enslaved woman were property of her owner. Marriage was legally possible after slavery. Unofficial unions existed between enslaved couples but were often broken up by slavers. Masters often sexually assaulted women. After slavery, marriages were legally recognized and Black families started new, hopeful lives. Hawkins Wilson was among them, officially marrying in 1867 to a freed woman in a Black church.

The Church

The church was another pillar of the Black community. Enslaved people worshipped in their own ways, mixing African religious customs with the Christian practices. There were religious leaders and regular worship in each slave community. However, slavers disliked this, and religious meetings were often held in secret. Many African Americans faced discrimination in biracial churches. Once slavery ended, free Black folks sought independence to worship in their own ways. Many started their own churches during Reconstruction. Hawkins Wilson joined the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Galveston, quickly becoming a leader there:

I am sexton of Methodist Episcopal Colored... I work hard all week. On Sunday I am the first one in the church and the last to leave at night, being all day long engaged in serving the Lord, teaching Sunday School, and helping to worship God.

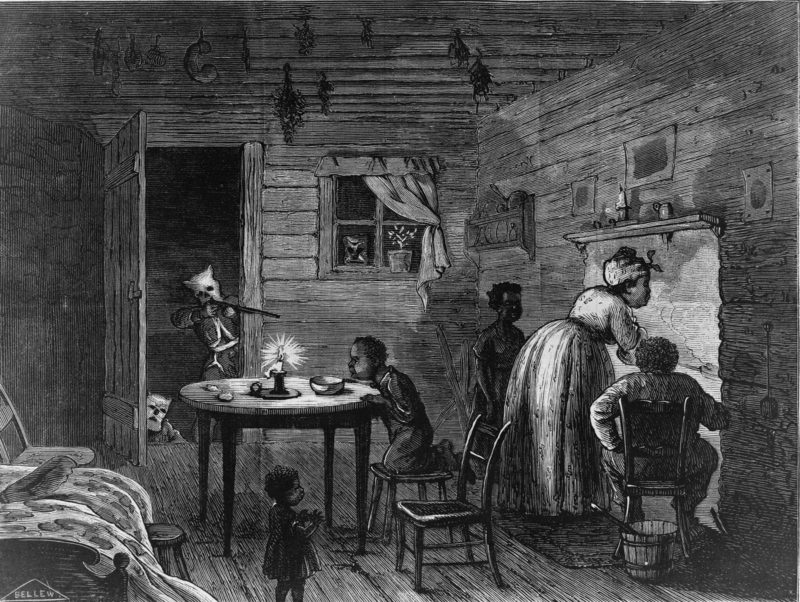

These new churches were controlled entirely by Black folks, and they were centers of the new Black communities. Churches were places of worship but also schools and political meeting places. As symbols of the new Black freedom, Black churches were often burned by white terrorists. Black ministers and preachers were terrorized, intimidated, and killed.

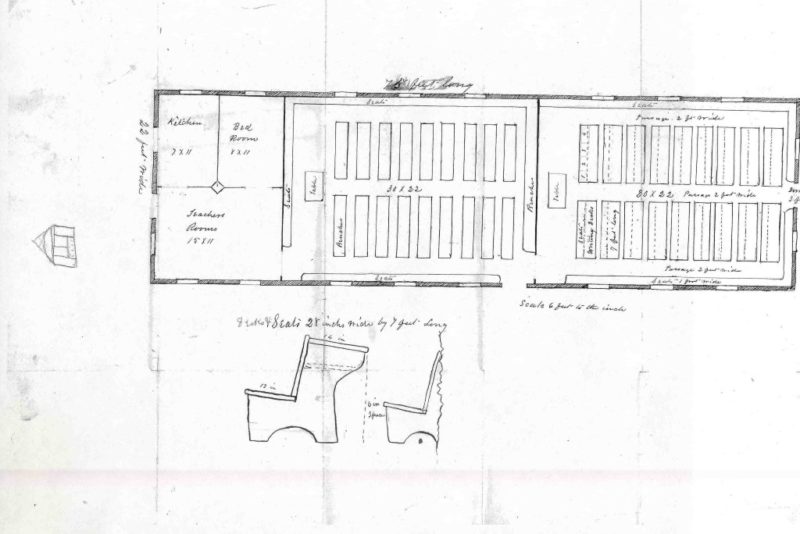

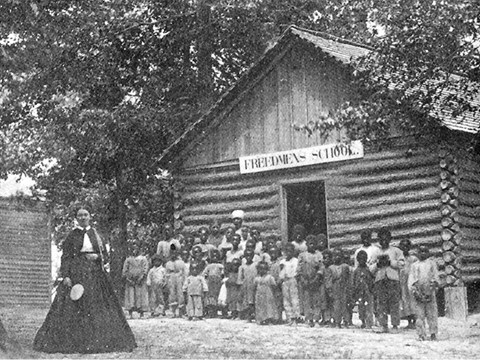

The School

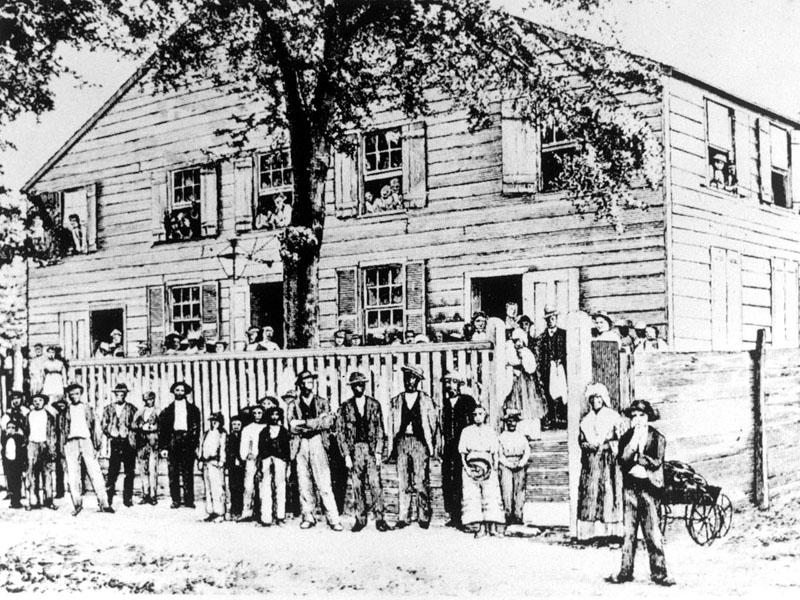

Just as churches became centers of the rising Black communities during Reconstruction, so too did schools. Slave masters forbade reading or writing. After the Civil War, Black folks tried to make the most out of their new status by becoming literate. Young and old alike went to schools to learn how to read and write. Literacy allowed them to negotiate contracts, stay informed of politics, and read the bible.

Public schools did not exist in the South for white or Black children before the Civil War. This meant new schools had to be planned, funded, constructed, and staffed. The newly free Black communities did this themselves. Just as with churches, schools were built wherever African Americans were. Teachers like Hawkins Wilson were leaders within the community, able to negotiate contracts on behalf of others, write to the government, and run for political office. Any school or teacher that taught Black people was a target of racial violence. "Nearly every colored church and school-house" near Tuskegee, Alabama was burned by white terrorists. White people who taught Black students were also terrorized.

The Black school, church, and family were essential parts of African American life after emancipation. Most freed people stayed in the South, and now they had the opportunity to form their own community in the open. The school, church, and family were important parts of that community, providing the hope of a better life away from their former masters. This meant the freedom to live with family, enjoy marriage, raise children, worship in the open, and teach the next generation.

The family, church, and school formed the basis for the new free Black communities across the United States. White terrorist violence started as soon as the Civil War ended, as white Southerners were enraged by independent Black communities. Churches and schools were destroyed by white supremacist violence, and the married Black household was under constant assault. Control of Black children was frequently contested. The dream of full political, social, and economic equality for African Americans would not be accomplished during Reconstruction because of this violence. However, the pillars of these new Black communities would remain a foundation for future efforts towards equality. As African Americans later fled North and West over the following decades, the church and family moved with them. White violence followed as well.

Sources and Further Reading

WEB Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America. New York: Russell & Russell, 1935.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, Update Edition. Harper Collins: New York, 2014. See 78-102.

For information about the change for women’s labor, see Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage.

Ira Berlin, Barbara Fields et al, ed. Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War

Ira Berlin and Leslie S. Rowland, ed. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African-American Kinship in the Civil War Era. New York: New York Press, 1997.

Learn more about the Freedmen’s Bureau and marriage here: https://sova.si.edu/record/NMAAHC.FB.M1875

https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/initiatives/freedmens-bureau-records

Jarrod Showalter is a graduate student pursuing a master's degree in Public History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His area of study is the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, with an emphasis on the era’s racial politics. His other work has covered the Jim Crow era, redlining, and the Early American Republic. He is a teaching assistant in the UWM History Department, where he teaches courses on early American history and the Holocaust. He has a bachelor’s degree in history and political science from Knox College in Galesburg, IL. Showalter is also a museum professional pursuing a graduate certificate in Museum Studies from UWM. He has worked in museums at the local, county, state, and national levels. He is originally from Ankeny, Iowa.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.