How Birmingham’s Youngest Mayor Tore Down a ’52-Foot Lie’

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

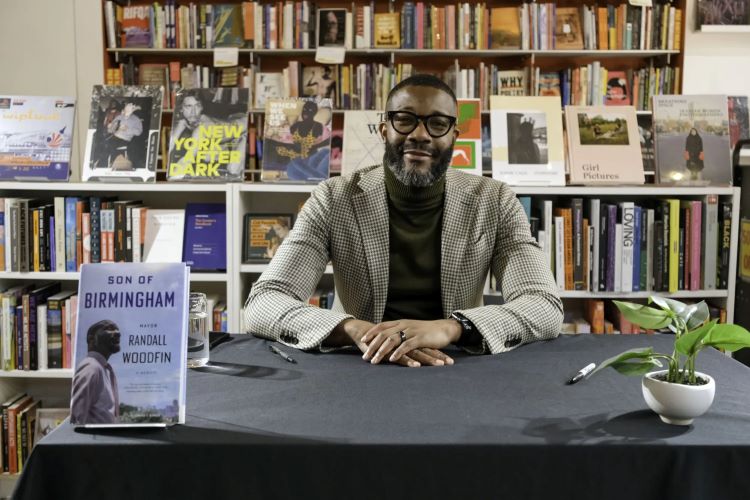

By Randall Woodfin, Word in Black

In an excerpt from his new memoir, Randall Woodfin reflects on fighting against the city’s racist history.

I promised our city that in 24 hours, I’d remove the monument that had haunted us for generations.

I had less than a day to do what lawmakers, activists, and lawyers couldn’t do over the course of dozens of years.

No pressure, right?

My team and I had to find a way to physically remove that massive structure, which seemed like a Herculean task in such a short amount of time.

Meanwhile, I had to play politics with the state.

I called both the state attorney general’s office and the governor’s office. I made my stance clear: If I had to choose between a civil fine and civil unrest, I was taking the fine. Birmingham was not having another night of unrest, not on my watch.

I knew there would be consequences, but I didn’t know how serious they could be. We were outright defying the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act. I thought to myself, “If I’m charged with a felony, I could be removed from office.”

[…]

The governor’s office understood and didn’t push back. The state attorney general, though, fined us $25,000.

[…]

Eventually, we found our crew: A general contractor from Mountain Brook, Alabama, a haul crew from Bessemer, Alabama, and a demolition crew from Cullman, Alabama.

Unless you’re a Birmingham native, it’s hard to convey how vastly different those three locations are. Mountain Brook is a city known for its affluence, while Bessemer lies on the opposite end of that spectrum. And until the 1970s, Cullman was known as a “sundown town”—a tag given to cities where Black folks weren’t allowed to live. We had to get out of town before sundown, or the consequences would be dire. These three different crews had never met each other. Frankly, they were nervous. But there was something astounding about these three very different walks of life uniting for an important cause.

It’s so very Birmingham.

[…]

We asked the crews to put cardboard over the logos on their trucks so they wouldn’t be identified. Meanwhile, Birmingham police secured the perimeter.

Media outlets were pissed—they wanted a front row seat. History was about to be made.

Head to the original article to learn how they made history by removing the monument of Jefferson Davis.

Many of these monuments were installed during Jim Crow as pushback against the fight for equal rights

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.