How John Lewis Became a Moral Force in America

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Brent Staples, New York Times

John Lewis was enrolled in a seminary in the Jim Crow city of Nashville when he embraced the belief that allowing himself to be beaten nearly to death in public would hasten the collapse of Southern apartheid.

In 1960, Lewis and his contemporaries carried that spirit into the sit-in campaign that forced Nashville to integrate its “white only” lunch counters. The following year, young protesters experienced homicidal levels of brutality when they boarded southbound Freedom Ride buses to challenge segregation in interstate transportation. When Lewis’s bus reached Montgomery, Ala., passengers were savaged by a white mob whose members carried every conceivable weapon — including bricks, chains, tire irons and baseball bats. Outside Anniston, Ala., Klansmen firebombed another bus and held its exit doors shut with the aim of burning the passengers alive.

The battering Lewis received four years later during the “Bloody Sunday” voting rights march in Selma, Ala., stands out for what happened next. Congress responded to the barbaric spectacle of state troopers bludgeoning demonstrators by finally outlawing the methods that the South had long used to prevent millions of Black people from registering to vote. Lewis was recovering from a fractured skull when Lyndon Johnson summoned him to Washington for the signing of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, the civil rights movement’s holy grail. L.B.J. admonished Lewis to get the white South “by the balls” — by registering legions of Black people to vote — and to “squeeze, squeeze ’em till they hurt.”

Even as Lewis celebrated, he was under siege in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the potent civil rights organization whose chairmanship he held. His critics within the group complained that their chairman was too chummy with the white man in the White House and mocked him for rushing to have his suits cleaned whenever the president called. A SNCC faction led by the charismatic Black nationalist Stokely Carmichael had rejected the doctrines of interracial cooperation and Gandhian nonviolence to which Lewis had devoted himself. In the spring of 1966, the faction shoved Lewis aside and elected the fiery Carmichael to lead them.

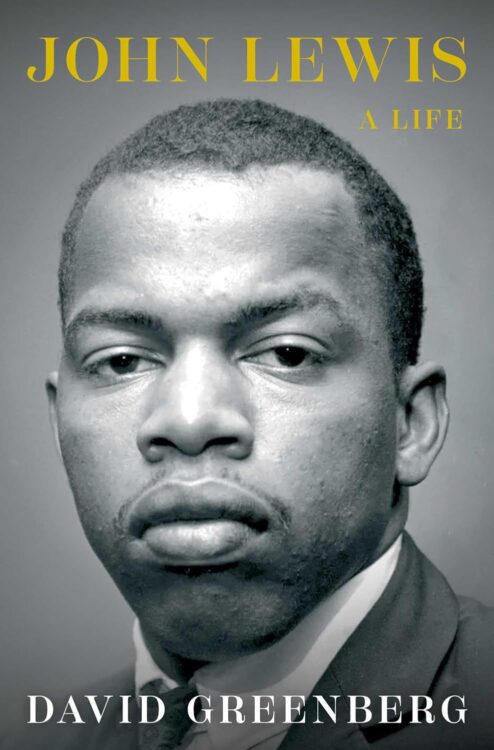

As the historian David Greenberg writes in “John Lewis,” his panoramic and richly insightful biography, the former chairman “found himself, at age 26, with no job, unmarried and unsure what to do with his life. The movement to which he had devoted his adult life was veering away from the ideals that had animated it. To remain in the struggle, he would have to find another path.”

The haloed sainthood attributed to Lewis at his funeral four years ago was by no means evident the day SNCC showed him the door. Greenberg argues that his subject achieved the stature of legend only after his memoir “Walking With the Wind” was published to rapturous acclaim in 1998, when he was entering his second decade as the congressman from Georgia’s Fifth District, a position he would hold for the rest of his life.

Learn about more activists who fought for equal rights.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.