In Compton, a School That Paved the Way for Generations of Black Artists

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By: Melissa Smith, The New York Times

In Compton, Calif., in the late 1960s and early ’70s, public school students sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” after the national anthem at the start of classes each day. It was a Black city. Following the Watts Rebellion — the uprisings that took place in August 1965 in the predominantly Black Watts neighborhood, just north of Compton in southern Los Angeles—white residents who hadn’t already left the area were desperate to get out. By the end of that decade, Compton’s population, which had previously been mostly white, was about 70 percent Black. “The difference between Compton in 1959 and in 1969 is almost like night and day,” says Robert Lee Johnson, a local historian. When the city elected Douglas Dollarhide, its first Black mayor, in 1969, he came into office with a majority Black school board and an entirely Black City Council. But keeping the city middle class was an uphill battle. The mass relocation of white-owned businesses led to sweeping job losses and soon Compton, which had formerly been “known for its housing and schools,” Johnson says, couldn’t afford to maintain either, let alone support the arts.

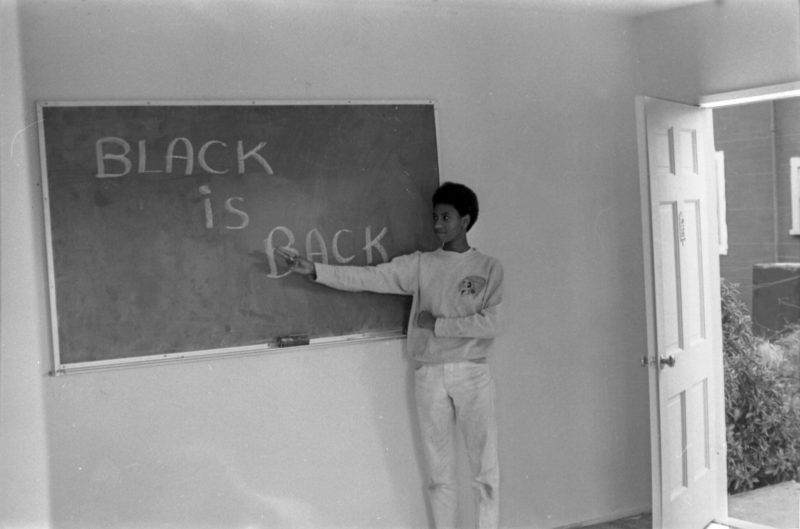

A student at the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton, Calif., where the syllabus was designed to instill in participants a sense of Black pride.

Willie Ford Jr. and the Compton Communicative Arts Academy Collection, Special Collections and Archives, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, California State University, Los Angeles

The academy’s first location was the Happening House, a white-shingled two-story home on East Indigo Street donated by the Salvation Army. With the help of students from Compton High School, Outterbridge renovated the residence as a space for workshops, and within months so many students had enrolled in classes that it became clear another building was needed. Powell arranged for the academy to expand into an abandoned warehouse that had, at one time, served as a skating rink.

Thanks to the academy, art also spilled out into the city, perhaps most prominently with the work of the local artist Elliott Pinkney, who became the C.A.A.’s — and by extension, Compton’s — unofficial muralist around 1970. Painted across local buildings, his colorful, layered tableaus helped advertise one of the academy’s talents and its sensibility as an institution intent on Black uplift. A few of his later works, some of which were made in collaboration with his son Arnold, remain: “Medicare 78” (1977), a tribute to health care workers in vibrant shades of cornflower blue and rust red, can still be seen on North Alameda Street near Rosecrans Avenue, and “Ethnic Simplicity” (1977), a portrait of the city’s multiculturalism, still stands about a mile north, though it has been partially painted over.

Read the full article here.

To learn more about Black Art, click here and here.

More Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.