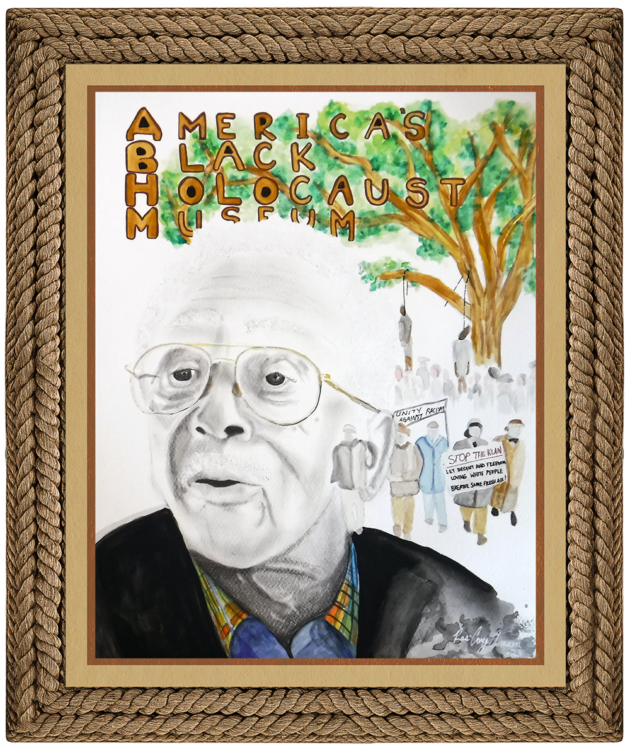

Inheriting Home: The Skeletons in Pa’s Closet

Share

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Stephanie Harp, MA

My Southern Family

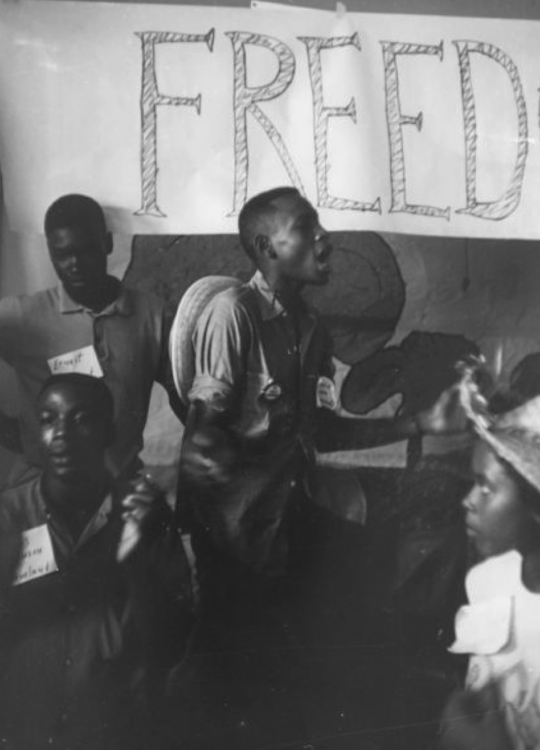

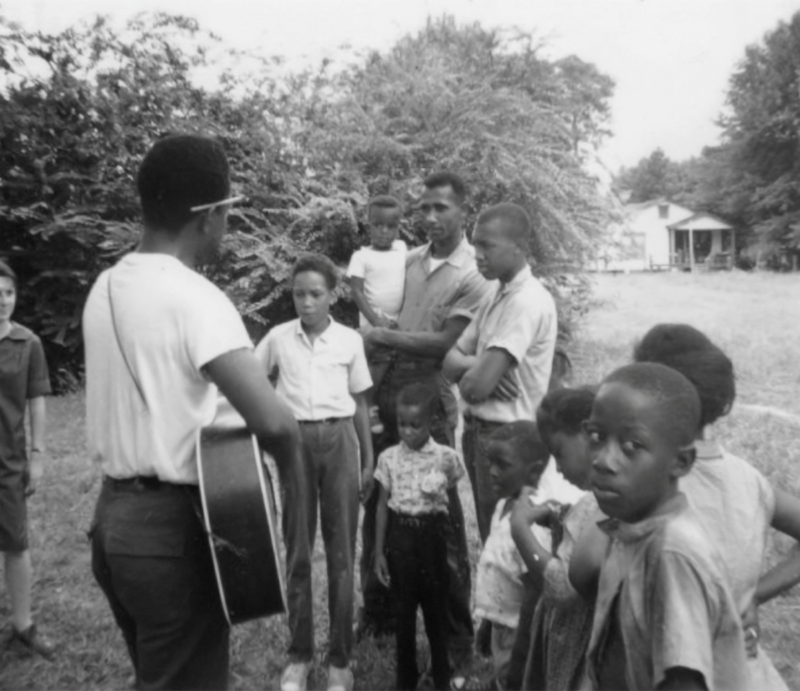

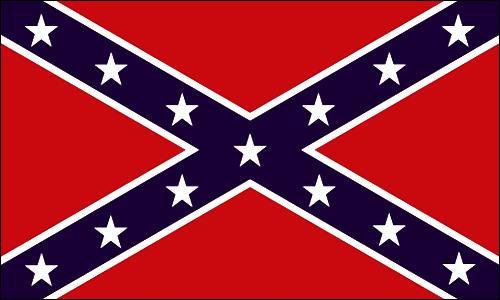

The South is a region of contradictions – warmth and violence, faith and hell-fire, friendliness and bigotry. Growing up, I lived in the South and away from it. But to my Southern family, home was Little Rock. With its store of family memories, Arkansas defined home for me, too. But embracing and claiming it as my own is prickly business. “Home” has closets of skeletons that are anything but comforting: the Lost Cause1, Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan, lynchings.

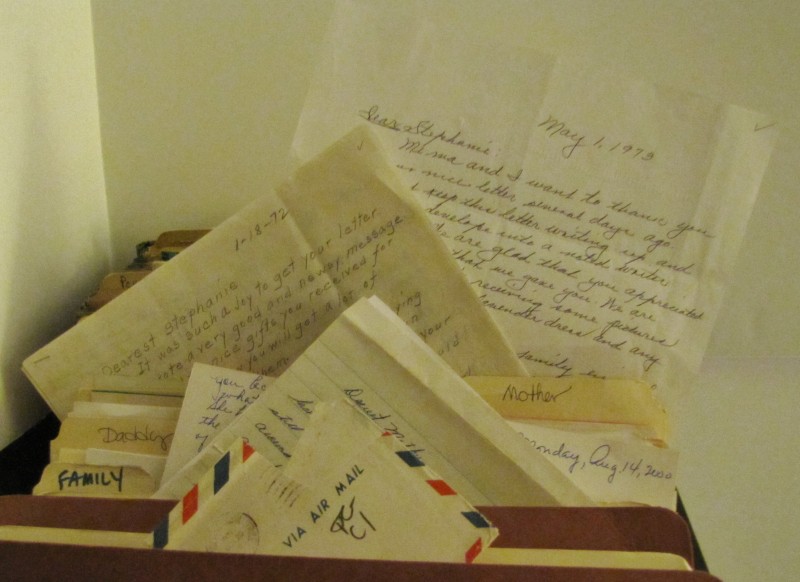

Sorting through the threads of love, violence, and inheritance, I began to wonder what family memories meant to me. Did I have to claim all of them? Or could I choose only ones I liked? In letters, photographs, journals, and stories, I saw ancestors who worked as telephone operators, electricians, Sunday School teachers, and small-time public officials. Like any family, mine laughed together, argued, grew old, and taught family memories to their children.

The Stories

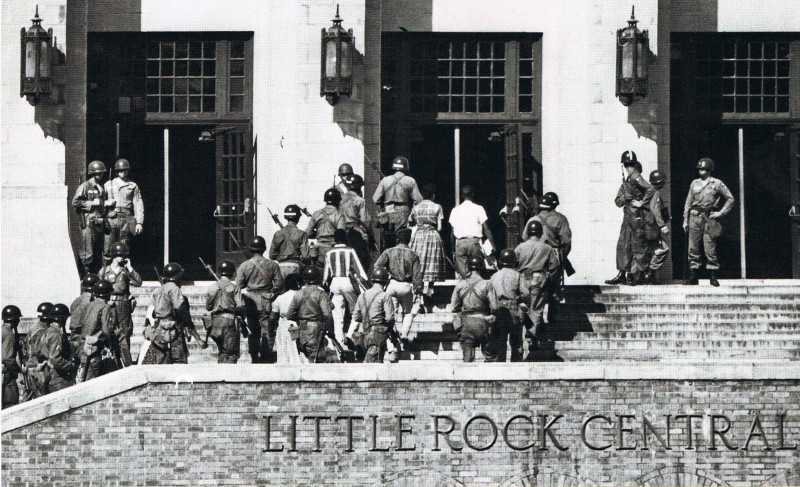

One family story with national significance was the 1957 desegregation of Little Rock Central High School.2 Growing up among its alumni, I heard about Eisenhower, the 101st Airborne, and the Little Rock Nine in mixed tones of subdued pride. Central had made international news, but only with negative articles about what happened there.

Something else I always heard: Pa, my grandmother’s father, was a deputy sheriff, a “peace officer,” as they were called then. Everyone was proud of this. He and my great-grandmother must have cut quite the dashing figures in the 1920s, a charming, popular couple hosting speakeasies in their shotgun house during Prohibition. They pushed back furniture on bare wooden floors to win Jitterbug contests. Their young daughters peeked around doorframes at the glamorous parties. My family clearly remembered the couple with admiration, even awe.

Another family story: a black man was lynched in the middle of Little Rock. The tone was similar to that used about Central High – shame at the blot on the city’s reputation, but just a bit of pride at the notoriety. I was too young to wonder how anyone possibly could be proud of a lynching.

Making the Connection

In 1993 my grandmother (Pa’s daughter) died and I inherited her papers, filled with the stories she’d always told me. Reading them one winter day, in my attic office of a house in Maine, I found pieces that formed not what I’d always heard as two separate stories, but a single one. Deputy Sherriff Pa helped commit the lynching, helped drag the man’s body into the city and burn it.

He helped? I began consuming everything I could find about lynchings – heroes who tried to stop them, complicit law enforcement, seemingly respectable businessmen who hid under robes of the Ku Klux Klan. As I read, I grew more and more angry at my newfound connection to it. Pa was among the peace officers who didn’t stop John Carter’s lynching. Pa’s car might have been the one that dragged Carter’s body through town.

History as Therapy

I kept reading, trying to forgive myself for having this nightmare in my background, in my genes. History as therapy, I called it. I wanted to forget my family’s past. But could I? If I said I inherited my love of books from my grandmother, could I ignore her father’s legacy of racism and violence? I began writing and rewriting John Carter’s story. I whined and raged about ignorance and justice, and my anger didn’t fade. Clearly, the therapy wasn’t working. I needed to know what had happened, but I also needed to know why.

I enrolled in a history master’s program. From lists compiled by the NAACP and Tuskegee University, I learned about thousands of lynching victims, in the South and elsewhere. I learned about upheavals of the 1920s. The Civil War defeat was still very real to that generation of white Southern men. Having lost at Appomattox, sixty years later white men thought they could conquer a different enemy: black men accused of attacking white women. When Southern whites of that decade saw lynching photographs, they wouldn’t have felt the shock that turns our stomachs today and makes us look away. A white Little Rock newspaper said, “This may be ‘Southern brutality’ as far as a Boston Negro can see, but in polite circles, we call it Southern chivalry, a Southern virtue that will never die.”3

Taking a stand would have been very difficult in Pa’s community. Some people did it, but Pa didn’t.

Pa's Legacy

With a fuller understanding of the circumstances, I don’t condone or excuse my great-grandfather’s actions. Like the Little Rock mob, I’d wanted a scapegoat. I’d wanted to despise Pa for the Southern history our family embodied. Or, I’d wanted proof his daughter was mistaken and he hadn’t done it. But nothing exonerated him. Pa did a horrible thing, and he wasn’t alone.

Neither am I. Others search their families for heroes or villains. Like me, they find ancestors who couldn’t – or wouldn’t – stand up to social and physical threats. We who have perpetrators in our families have to claim the legacies they left us. We have to speak against it. Telling stories can make a difference; I’ve seen it happen. And burying unpleasant history keeps us from learning its lessons. As a nation, we still have many lessons, both behind and ahead of us. As long as we keep trying, keep talking, we have a chance of learning them.

NOTE: On February 15, 2013, Stephanie and George Fulton, great-grandson of John Carter, joined together in a public forum in Little Rock, AR, to explore the different perspectives on the lynching in the community. They now plan to work together on a film and newsletter about the case.

Endnotes/Sources

1 Lost Cause. Encyclopedia Virginia. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lost_Cause_The

2 Central High School. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=718

3 Little Rock Daily News, quoted in Crisis 15 (April 1918), 288-29. Reference in Leon F. Litwack, “Hellhounds,” Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Santa Fe: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000), 24.

Stephanie Harp ©2012. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Stephanie Harp, MA, is a writer and journalist who holds a master’s degree in U.S. History from the University of Maine. Her family roots lie in Arkansas and Louisiana. www. For more information about Stephanie's work, visit https://www.stephanieharp.com/inheritance/

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

I just would like to say I found your story inspiring and lost for words and PEA2⃣CE B WITH U