Lett’s Stand Against Debt Peonage Cost His Life

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Newest Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Murdered in: Tunnel Springs, Alabama | Aug 23, 1905

SCHOLAR-GRIOT: Sarah Sexton Miller

Oliver Lett. The name is one of nearly 2000 in ABHM's online Memorial to the Victims of Lynching, and one of the 4,400 you will see if you visit the Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. The monuments alone are enough to move one to tears, but Oliver Lett was – is – so much more than a name. They all are, but this is the story of Henry Oliver Lett.

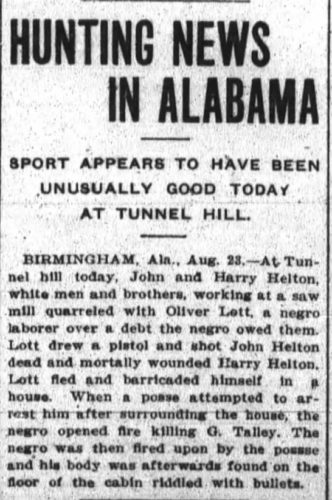

Ft Wayne (Indiana) Daily News, August 23, 1905

The Civil War officially ended on April 9, 1865, and Samuel and Laura Lett (1870 United States Federal Census, 2009), who had most likely been enslaved and living in Monroe County at the war’s end, soon began their family with the birth of their first son, James, followed in August of 1866 (1900 United States Federal Census, 2004) by their second son Oliver. Sam, like most freedmen after the war, registered to vote in 1867 (Alabama, U.S., Voter Registration, 1867, 2015). Life was looking good for the Lett family. By 1888 they would have five more children, two more boys and three girls.

At the age of 23 Oliver married Mary East and began his own family, which included three daughters and one son. By 1900, they were renting a farm in Monroe County, which they shared with Oliver’s brother James (1900 United States Federal Census, 2004). No one could have imagined the shocking and gruesome fate that awaited Oliver just five years later in Tunnel Springs.

On August 23, 1905, Oliver became the topic of headlines that seem unfathomable in the present era. The Fort Wayne Daily News in Fort Wayne, Indiana would boast “Hunting News in Alabama – Sport Appears to Have Been Unusually Good Today at Tunnel Hill” (Fort Wayne Daily News, 1905). The ‘sport’, it turns out, was the lynching of Henry Oliver Lett.

There are multiple accounts concerning the events leading up to Lett’s death, each one slightly different, and some with painfully obvious bias and racism. Only upon piecing together the events from all accounts does the story begin to have some semblance of truth.

What is known beyond a doubt is that Oliver Lett was working off a debt to Mr. G. Talley at a sawmill he owned. At some point, Mr. Lett believed he had repaid his debt in full, but Talley did not. When Oliver did not report to work the following day, Talley sent two brothers who also worked for him to Oliver’s house to demand that he come to work or repay Talley’s money. The brothers, John and Harry Helton, found Lett at his home. Oliver shot both men, killing John and wounding Harry, who survived to give his account of what happened at the Lett house. (The Monroe Journal, 1905)

Birmingham News August 23, 1905

After Harry Helton “sounded the alarm”, a group of heavily armed men who are referred to in every article about the incident as a posse, led by G. Talley himself, proceeded to Lett’s house. In all accounts, this act ended with the deaths of both Talley and Henry Oliver Lett, and the law did not become involved until after the deaths had occurred. The sheriff arrived to find Oliver’s body on the ground, “riddled with bullets.” (The Monroe Journal, 1905)

What really happened when the Helton brothers approached Oliver Lett? Why did he shoot them? These are questions that might have been answered in a trial, had there been one. Instead, a so-called posse, more likely a lynch mob, became judge, jury, and executioner that day in 1905. Newspapers all across the country villainized the “Desperate Negro” (The Monroe Journal, 1905) who shot three white men, killing two. The San Francisco Chronicle added a house fire to the already gruesome story of the killing, demonstrating that the newspaper accounts of the time were sometimes embellished (San Francisco Chronicle, 1905).

Sadly, the story of Mr. Lett has only been told publicly from the points-of-view of the men who participated in the killing and those who supported them. After reading the many newspaper accounts from the time, family members such as Lett’s great-great granddaughter, Stephanie Northern, believe Oliver Lett made a stand for freedom after finding himself entangled in indentured servitude. When Talley sent the Heltons to secure his laborer or make him pay, Oliver Lett refused to return to servitude and indeed shot the brothers, though whether in anger or self-defense, we can never know. When the mob came for him, Lett certainly knew that he would not escape with his life, but in one last show of defiance, he made a valiant stand, taking his would-be ‘master’ to the grave with him.

Descendants of Henry Oliver Lett on a school field trip along the Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights Trail in 2019.

Works Cited

1870 United States Federal Census. (2009). Retrieved from ancestry.com.

1880 United States Federal Census. (2010). Retrieved from ancestry.com: ancestry.com

1900 United States Federal Census. (2004). Retrieved from ancestry.com:

Alabama, U.S., Voter Registration, 1867. (2015). Retrieved from ancestry.com:

Fort Wayne Daily News. (1905, August 23). Hunting News in Alabama. Fort Wayne Daily News

Retrieved from newspapers.com:

San Francisco Chronicle. (1905, August 24). San Francisco Chronicle, p. 2.

The Atmore Record. (1905, August 24). Double Murder. The Atmore Record, p. 1.

The Monroe Journal. (1905, August 24). Bloody Tragedy. The Monroe Journal, p. 3.

Sarah Sexton Miller holds a master’s degree in Collaborative Education and has been an English Language Arts teacher in the Conecuh County School system for the past seven years. She has also taught history and genealogy. Mrs. Miller is a self-taught traditional and genetic genealogist whose previous works include a feature article in Alabama Heritage as well as a book on the lynchings of the Kelley-Hipp gang in Greenville, Alabama. She learned of Henry Oliver Lett while teaching Genealogy at Southside Preparatory Magnet Academy in Evergreen, Alabama and knew she wanted to tell his story as well.