Opinion: The 1936 manual that enshrined racism in America’s housing

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Elizabeth Korver-Glenn for CNN

The New York Times recently published a story about two Black scholars in Baltimore who say their home was undervalued by hundreds of thousands of dollars because of their race and have filed a lawsuit against an appraiser and mortgage lender in Maryland. Their story is rightfully raising questions about how racism shapes the contours of Americans’ experiences in the real estate market and what individual homeowners can do about it.

But appraisal discrimination is not just a story about individual racist appraisers or personal experience. It is a story about the racism that infuses the appraisal industry and the housing market as a whole.

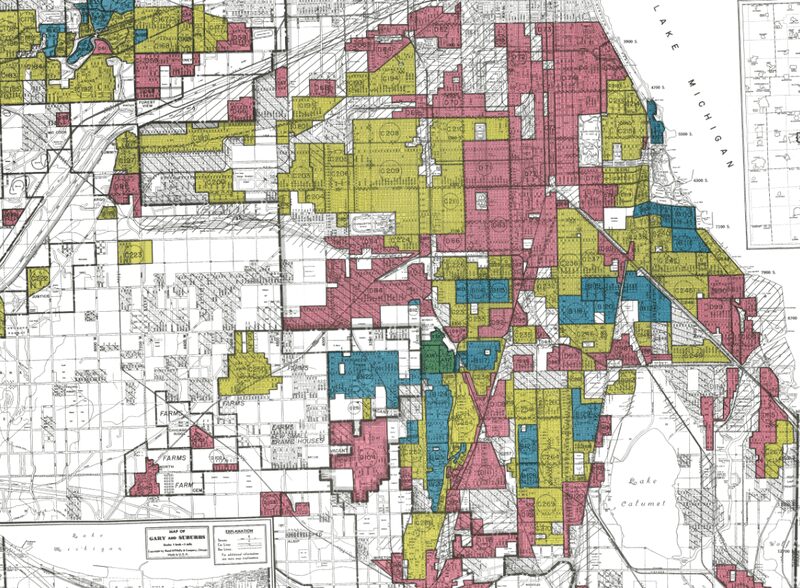

This racism took root and began to flourish almost 100 years ago, in the appraisal industry’s earliest days. Choosing among multiple appraisal methods, influential industry players like Frederick Babcock decided that the best way to determine home value and property financial risk was to compare for-sale homes to other, previously sold homes in the same or similar neighborhoods. Importantly, in this model — known as the sales comparison approach — neighborhoods were rated on how “desirable” or “risky” appraisers perceived them to be.

Babcock, who oversaw the initial “Underwriting Manual” for the then-newly formed Federal Housing Administration (FHA), explicitly defined neighborhood desirability and risk by neighborhood racial and socioeconomic composition. For instance, the 1936 manual (Part II, Paragraph 233) explained:

“The Valuator should investigate areas surrounding the location to determine whether or not incompatible racial and social groups are present, to the end that an intelligent prediction may be made regarding the possibility or probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social and racial occupancy generally leads to instability and a reduction in values.”

This manual, among other federal and industry-level policies and procedures, established racism as the logic undergirding the sales comparison approach to determining neighborhood and home value. Stable White and affluent neighborhoods were defined as “desirable” and “low-risk.” Communities of color and low-income neighborhoods were defined as “undesirable” and “high-risk.”

Finish reading how people of color were barred from homeownership.

Read about the couple who inspired this article, how racial barriers persist in real estate, and how one Chicago suburb responded to this crisis.

ABHM’s breaking news page has more relevant stories.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.