Popular and Pervasive Stereotypes of African Americans

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From the National Museum of African American History & Culture

Stereotypes of African Americans grew as a natural consequence of both scientific racism and legal challenges to both their personhood and citizenship. The ruling in the 1857 Supreme Court case, Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford, wherein Chief Justice Roger B. Taney dismissed the humanness of those of African descent, set a legal precedent for African Americans to be reduced to caricatures in popular culture.

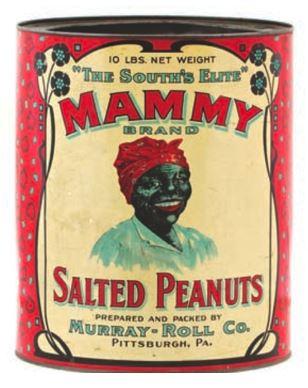

Decades-old ephemera and current-day incarnations of African American stereotypes, including Mammy, Mandingo, Sapphire, Uncle Tom, and Watermelon, have been informed by the legal and social status of African Americans. Many of these stereotypes developed during the height of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and were used to reinforce the commodifying of Black bodies and particularly aspects of enslavement. For instance, an enslaved person forced under violence to work from sunrise to sunset could hardly be described as ‘lazy,’ yet laziness, as well as characteristics of docility, backwardness, lasciviousness, treachery, and dishonesty, historically became characteristic of African Americans.

The Mammy stereotype developed as an offensive racial caricature constructed during slavery, and popularized largely through minstrel shows. Enslaved black women were highly skilled domestic works, working in the homes of white families and caretakers for their children. The trope painted a picture of undying loyalty to their slaveholders as caregivers and counsel, that ultimately sought to legitimize the institution of slavery. The Mammy stereotype gained increased popularity after the Civil War and during the Consumer Revolution, which saw her robust, grinning likeness attached to mass produced consumer goods from flour to motor oil. Considered a trusted figure in white imaginations, mammies represented contentment and served as a nostalgia for whites concerned about racial equality.

The Pearl Milling company’s incarnation of the smiling domestic, Aunt Jemima, became synonymous with the mammy stereotype in 1899 when real-life cook Nancy Green was hired to portray the character at state and world fairs. The stereotype of the overweight, self-sacrificing and dependent mammy figure would also grow alongside the American film industry through works including Birth of a Nation (1915), Imitation of Life (1934), and Gone with the Wind (1939)…

Read full article here

See more NMAAHC collections here

More Breaking News here

View more galleries from the ABHM here

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.