Read Barack Obama’s Eulogy for John Lewis

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

“He, as much as anyone in our history, brought this country a little bit closer to our highest ideals.”

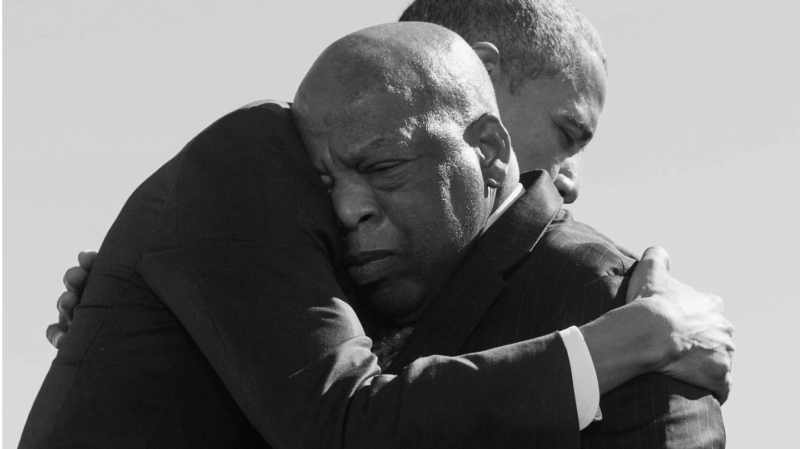

Former President Barack Obama delivered a eulogy today honoring Representative John Lewis of Georgia, who died July 17 after a decades-long career in the House of Representatives. Lewis, a civil-rights icon who led the 1965 march in Selma, Alabama, across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and spoke at the March on Washington, spent his congressional years advocating for voting rights and equality for Black Americans. Known as the moral “conscience” of the Congress, Lewis lay in state for two days in the Capitol this week.

James wrote to the believers, “Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance. Let perseverance finish its work so that you may be mature and complete, lacking nothing.” It is a great honor to be back in Ebenezer Baptist Church in the pulpit of its greatest pastor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to pay my respects to perhaps his finest disciple. An American whose faith was tested again and again, to produce a man of pure joy and unbreakable perseverance: John Robert Lewis.

To those who have spoken, to Presidents Bush and Clinton, Madame Speaker, Reverend Warnock, Reverend King, John’s family, friends, his beloved staff, Mayor Bottoms, I’ve come here today because I, like so many Americans, owe a great debt to John Lewis and his forceful vision of freedom.

You know, this country is a constant work in progress. We’re born with instructions: to form a more perfect union. Explicit in those words is the idea that we’re imperfect. That what gives each new generation purpose is to take up the unfinished work of the last and carry it further than any might have thought possible. John Lewis, first of the Freedom Riders; head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; youngest speaker at the March on Washington; leader of the march from Selma to Montgomery; member of Congress, representing the people of this state and this district for 33 years; mentor to young people—including me at the time—until his final day on this Earth, he not only embraced that responsibility, but he made it his life’s work. Which isn’t bad for a boy from Troy.

John was born into modest means—that means he was poor. In the heart of the Jim Crow South to parents who picked somebody else’s cotton. Apparently he didn’t take to farm work. On days when he was supposed to help his brothers and sisters with their labor, he’d hide under the porch and make a break for the school bus when it showed up. His mother, Willie May Lewis, nurtured that curiosity in this shy, serious child. “Once you learn something,” she told her son, “once you get something inside your head, no one can take it away from you.” As a boy, John listened through the door after bedtime as his father’s friends complained about the Klan. One Sunday as a teenager, he heard Dr. King preach on the radio. As a college student in Tennessee, he signed up for Jim Lawson’s workshops on the tactic of nonviolent civil disobedience. John Lewis was getting something inside his head. An idea he couldn’t shake. It took hold of him. That nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience were the means to change laws but also change hearts and change minds and change nations and change the world.

So he helped organize the Nashville campaign in 1960. He and other young men and women sat at a segregated lunch counter, well dressed, straight back, refusing to let a milkshake poured on their heads or a cigarette extinguished on their backs or a foot aimed at their ribs—refuse to let that dent their dignity and their sense of purpose. And after a few months, the Nashville campaign achieved the first successful desegregation of public facilities of any major city in the South. John got a taste of jail for the first, second, third—well, several times. But he also got a taste of victory, and it consumed him with righteous purpose and he took the battle deeper into the South.

Read the full eulogy here

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.