Silent Cavalry review: Howell Raines’ fine work on southern resistance

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Charles Kaiser, The Guardian

The former New York Times editor’s remarkable book on Alabamians fighting for the Union in the civil war, and his own family history

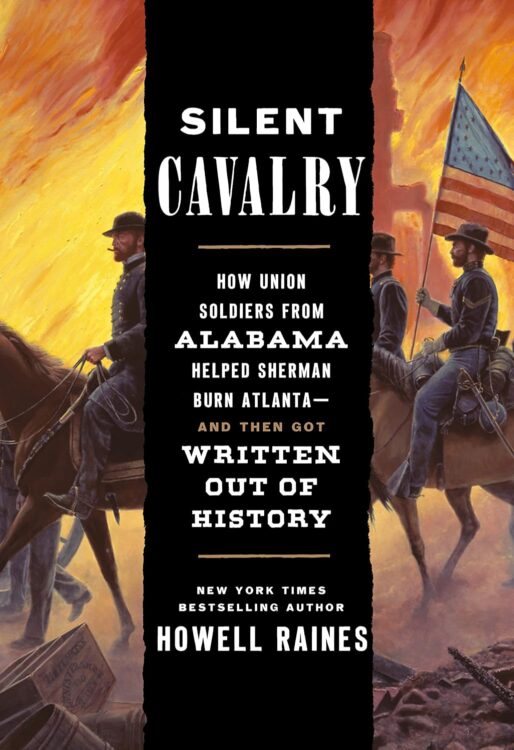

The subtitle of Silent Cavalry is How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta – And Then Got Written out of History. Those startling and nearly unknown stories form the spine of Howell Raines’ tremendous new book, but they were not the fuel that propelled him through decades of painstaking research.

What drove this Alabama native to write these 477 pages (before the notes) was a need for absolution – a feeling that was especially powerful in a Birmingham native, then 20, who was humiliated when his hometown became world famous. That happened in 1963, when the public safety commissioner, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, used clubs, high-pressure hoses and snarling German shepherds to halt a march of more than a thousand non-violent protesters determined to end the century of white supremacy that followed the American civil war.

Raines is a former executive editor of the New York Times and the author of a much-admired oral history of the civil rights movement whose title gives another clue to his motivation here: My Soul Is Rested.

As a journalist, he was famous for the cut-throat ambition that pushed him to the top of the Times news department – a perch he lost after less than two years when he was unable to contain a scandal produced by a suspiciously energetic reporter who turned out to be a serial fabulist. But Raines’ road to redemption wasn’t very connected to his life as a journalist. From the evidence in his new book, what mattered most was a fierce quest to find as many relatives as possible who fought against the Confederacy 80 years before he was born. That was the most powerful way he could separate himself from the infamous Alabamians of his youth, Bull Connor and George Wallace, the segregationist governor who ran for the White House.

[…]

A big part of this multi-layered narrative is devoted to the campaign of prominent historians to suppress the story of non-slave-owning Alabamians who supported the Union. That was just one consequence of historians’ larger effort to rebrand the war, to abolish slavery as its cause and instead tell “a tragic story of undeserved suffering inflicted on a noble, if misguided, class of southern aristocrats on their plantations and the dashing knights of the rebel army”.

[…]

There are many other pleasures in this book, including an account of WEB Du Bois offering the only challenge to mainstream historians at a 1909 meeting of the American Historical Society. His paper on Reconstruction and Its Benefits would make him a permanent outsider to a profession dominated by professors who believed Black officeholders had presided over a “tragic decade” of political corruption. Du Bois pointed out that Reconstruction actually produced the first public schools in the south, fairer taxation and advances in public transportation and economic development.

“Seldom in the history of the world has an almost totally illiterate population been given the means of self-education in so short a time,” Du Bois said. Nobody listened.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.