The Biggest Surprise at the Met’s Egypt Show? Live Performance

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Aruna D’Souza, The New York Times

Black artists have long claimed ancient Egypt as their own. Now they’re telling their stories in person on the museum’s floor.

The artist Lorraine O’Grady once wrote of her third-grade geography teacher pulling down a map and saying, “Children, this is Africa, except Egypt — which is part of the Middle East.” Her teacher was merely repeating what archaeologists, curators and art historians had long insisted — that Egypt was more “Mediterranean” than “African,” and a precursor to the achievements of Greek and Roman civilizations. But it defied what O’Grady could see with her own eyes.

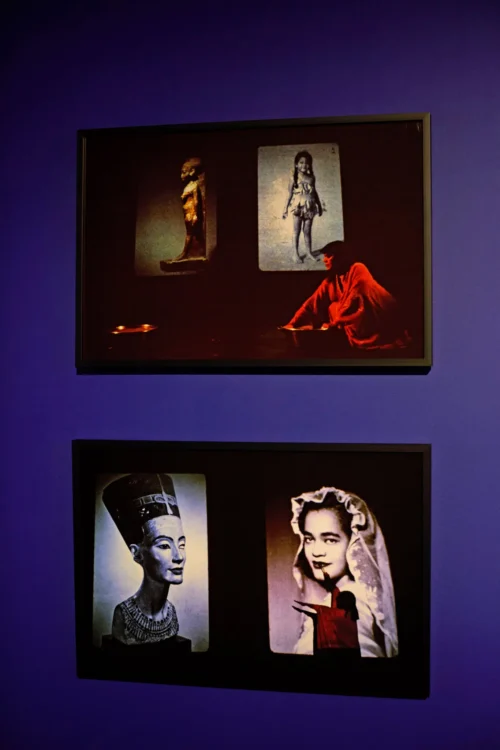

The memory, along with a trip to Cairo in the early 1960s, led O’Grady to dive into a study of the history of Egypt. Her research resulted in one of O’Grady’s first performance pieces, “Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline” (1980), in which she observed the almost uncanny resemblance between Queen Nefertiti’s relatives and O’Grady’s mixed-race family. Maybe Egypt and Africa weren’t as separate as Egyptologists wanted us to believe.

“Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline” and a later photo series, “Miscegenated Family Album,” based on that performance, are at the heart of a major exhibition opening Nov. 17 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. Titled “Flight Into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876 — Now,” it will feature almost 200 works made largely by African American artists looking to define their cultural history after the violent legacy of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which severed people of African origin from their roots. (That historical injustice went hand in hand with the denigration of African culture as inferior to the greatness of Europe.) For Black artists from the 19th century to today, claiming ancient Egypt as their own has been a way of asserting agency and power.

The exhibition, curated by the Met’s Akili Tommasino with McClain Groff, will include painting, sculpture, photography, installation and video, along with album covers, media and fashion by artists across disciplines and generations. They include the visual artists Aaron Douglas, Loïs Mailou Jones, Jacob Lawrence and Jean-Michel Basquiat; the comedian Richard Pryor; the Afrofuturist band leader Sun Ra; and the singer Solange Knowles.

To a degree unprecedented at the Met, it will also feature live performances that draw on ancient Egyptian themes. Eleven artists will present works in a “performance pyramid” embedded within the exhibition. This is not the first time the Met has incorporated performance into its galleries — Jacolby Satterwhite’s Great Hall commission in 2023 was a spectacular example. But this is the first time performance has been so interwoven in a show.

“Performance is an integral part of this history, and I couldn’t envision mounting this exhibition without giving it its proper space,” Tommasino said in a recent interview.

[…]

The Met has long sequestered ancient Egypt and African art at opposite ends of the building. The African collection is housed upstairs, in the glass-walled Michael C. Rockefeller wing on the south side (and closed for renovation until May 2025). Critics and artists have clamored for a deeper connection to the Egyptian wing, on the north side. A temporary installation titled “The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality” (which ran through October) paired holdings from West and Central African and Ancient Egypt, giving a glimmer of how the relationship of the two collections could meld.

Although Hollein, the Met director, refers to Egypt as “an African civilization” in communications about the new show, exhibitions like “The African Origin of Civilization” and “Flight into Egypt” will likely have little impact on how the permanent collection will be shown once the Rockefeller wing is reopened.

The Met will not introduce objects from the Egyptian collection into the Rockefeller wing. “The Met’s Ancient Egyptian collection will remain where it has always been in the Egyptian Wing,” the museum said in a follow-up email statement.

The continuing distinction between the two collections preserves what Tommasino, in a surprisingly frank statement in the catalog, describes as “Egyptian exceptionalism.”

For Stewart, the composer, the persistence of that framing makes his part in “Flight Into Egypt” — a show about the way African Americans have challenged such understandings for the past 150 years — even more urgent.

“This is an exhibit at one of the, if not the, most lauded art institutions in the world,” he said. “To do it in the belly of the beast, so to speak, feels like a big, subversive statement.”

Read the whole article here.

Visit “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now” virtually.

Explore ABHM’s own gallery African Peoples Before Captivity to learn more about precolonial African civilization and culture.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.