The Double Struggles of June Jordan, Poet and Social Activist

Share

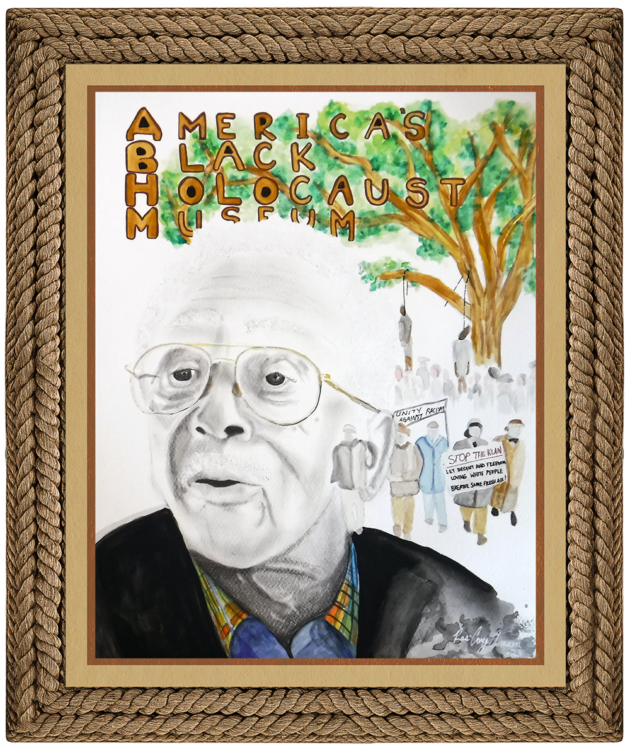

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Anna Strong

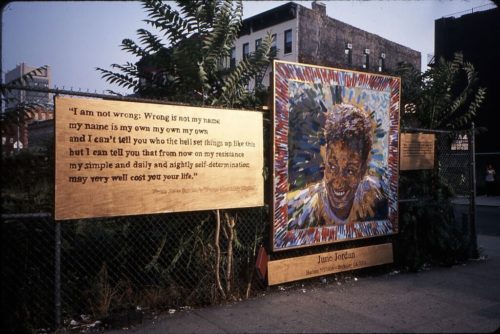

June Jordan posing for the cover of her book, Moving Towards Home. 1989. Gwen Philips.

“But life itself compels an optimism. It does not seem reasonable that the majority of the peoples of the world should finally, lose joy, and rational justice as a global experiment to be pursued and fiercely protected. It seems unreasonable that more than 400 million people, right now, struggle against hunger and starvation, even while there is an arable earth aplenty to feed and nourish every one of us. It does not seem reasonable that the color of your skin should curse and condemn all of your days and the days of your children. It seems preposterous that gender, that being a woman, anywhere in the world, should elicit contempt, or fear, or ridicule, and serious deprivation of rights to be, to become, to embrace whatever you choose...”[1]

This quote exemplifies the life that June Jordan led and just how much of herself she put into all of her work, from her shortest poems to her longest books. She was an activist to say the least and she believed that the best way to address the social and political climate of her time was through her writing. Her writing changed the way that people read poetry, the way that they looked at the events happening in the world around them, and the way that they viewed Jordan an author. The quote above hints at some of the topics that she often discussed within her pieces of literature, but even still there was so much more and that is exactly what this exhibit is dedicated to; the life and work of June Jordan.

Jordan's Early Life and "Double Struggles"

She was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York on July 9, 1936 to two Jamaican immigrant parents. Due to this she did not have what some would describe as a “traditional upbringing”. It was for this reason that she began to write at a very young age, using her writing as an outlet. Her parents were not like most at the time, as they were stricter and more demanding of her, especially her father.

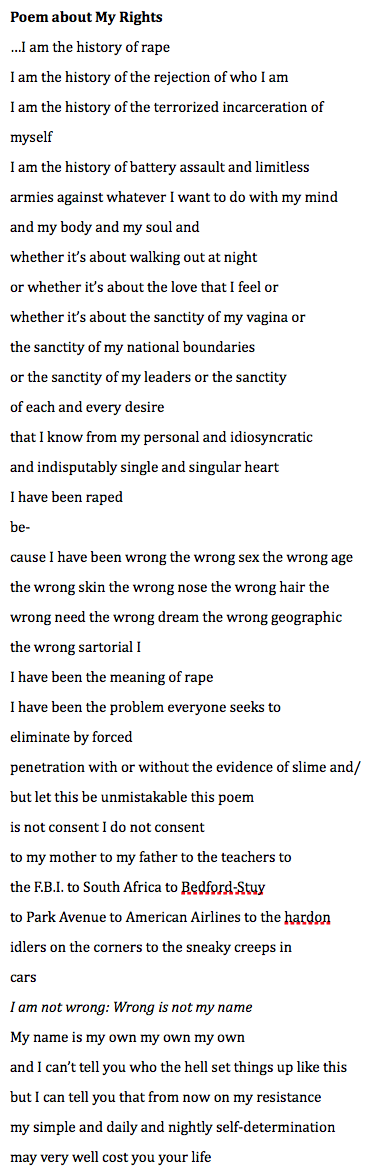

This is evident in her work. In her poem, Poem about My Rights, she wrote, “Before that /it was my father saying I was wrong saying that /I should have been a boy because he wanted one/a /boy and that I should have been lighter skinned and /that I should have had straighter hair and that /I should not be so boy crazy but instead I should /just be one/a boy...”[2]

Through this poem, readers were able to gather an understanding of the problems that Jordan faced within her own home, as if the problems that she faced when she walked outside into the world weren’t enough. Jordan had what many have come to know as a “double struggle”. This means that she struggled twice as much as the average American because not only was she black, but she was also a female and she felt it even in the confines of her own home.

Resilience In the Face of Trauma

Jordan at one point said that she had encountered many bullies throughout her life due to her Jamaican background, and the fact that she was small and short, however, she named her father as one the first regular bullies in her life (Jordan, Civil Wars: Selected Essays). In another one of her books, Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood, she even wrote about the times that he had beaten her: “Like a growling beast, the roll-away mahogany doors rumble open, and the light snaps on and a fist smashes into the side of my head and I am screaming awake: ‘Daddy! What did I do?!’”[3]

Another traumatic event that Jordan wrote about which had an influence on both her life and her writing was when she was raped. She wrote about this event and her process of coping with it. In Poem about My Rights Jordan wrote that she had once thought she was in the wrong for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. However, she came to terms with the fact that she was not in the wrong. She realized, instead that there was something wrong with the system, which would allow for a person to commit an act of sexual assault and not have any penalties. Within this poem, not only was Jordan critiquing the system, but she was also addressing the problems that she often faced growing up as a female, and those problems were not singular to her. This poem was a message to young females growing up in America, a predominantly male society. She wanted to let them know that even if they face adversity, as she often did, it is not because they have done something wrong. Instead, women should be free to be who they are and who they are becoming and they should be unapologetic about it. “I am not wrong: wrong is not my name,” says Jordan.[4]

These traumatic events shaped her into the resilient woman that she became. Although her father bullied and beat her she still found a way to see good in their relationship. She stated in an interview before her loss to breast cancer in 2002 that she never doubted that he loved her and thought highly of her and her abilities.[5] She also began to cope with her experience with sexual assault as she often explored the issue of sexual identity and sex within a number of her poems. Many of the traumas that June Jordan overcame throughout her lifetime, she saved for her poems.

June Jordan at her childhood home seated at her piano. 1986. Scanned form reproduced photo. Radcliffe Institute.

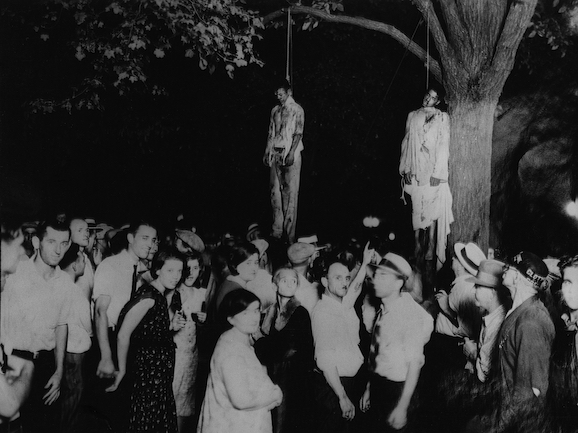

Living Black in the US of A

Although Jordan was actually Jamaican there were certain experiences that she could not escape as a resident of Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York, and as an American citizen. When people looked at her, they saw another black person and therefore they judged her and treated her the same way as they would have any other. Therefore, her writings tackled an array of topics, from black love to police brutality. Her poem, entitled Poem about Police Violence, encompasses both of those topics as she flows between different techniques and auras within the poem.

“What you think would happen if /everytime they kill a black boy /then we kill a cop /everytime they kill a black man /then we kill a cop /you think the accident rate would lower subsequently? /Sometimes the feeling like amaze me baby /comes back to my mouth and I am quiet /like Olympian pools from the running /mountainous snows under the sun...”[6]

Poetry Spots: June Jordan reads "Song of the Law Abiding Citizen"

What Would I Do White

She also dedicated her poem What Would I Do White to tackling this issue. Within this poem she made it obvious that she couldn’t even imagine white because it would be an entirely different lifestyle than the one that she had led. She ends the poem with, “I would do nothing. That would be enough.”[7] These two lines alone would have been sufficient for an entire poem. It emphasizes the differences in lifestyles while letting the reader know a little bit about her struggle as an African American. It tells the reader that unlike the alternate lifestyle which she was writing about, she has had to work in her life. She has had to work to be accepted in her family, work to be respected as a female within society, work to be equal in the eyes of the police and government officials while witnessing police brutality and corruption, and she has had to work to become the person that she was destined to be in such a demanding and hurtful world. And it is partially because of that simple difference, that she was pushed to write many of her better pieces of work.

Although, the purpose of the poem was not so that she could speak poorly about white Americans, but rather to demonstrate that life as a white American is much different from that of an African American. Within the poem she also wrote, “I would forget my furs on any chair. /I would ignore the doorman at the knob...”[8] Many will read these lines and assume that she is alluding to the fact that whites are careless and ignorant, however these lines have a much deeper meaning. They hint at the fact that wealth is also something that separates her life from that of a white American’s. She would not have furs to drape anywhere, nor would she be living in a house with a doorman ready to open and close the door at her will. Jordan worked hard all of her life, partially because she was a single mother to her son, yet she still didn’t live anything close to the lifestyle of the character that is described in the poem. How could she live such a lifestyle when there was still so much work to be done?

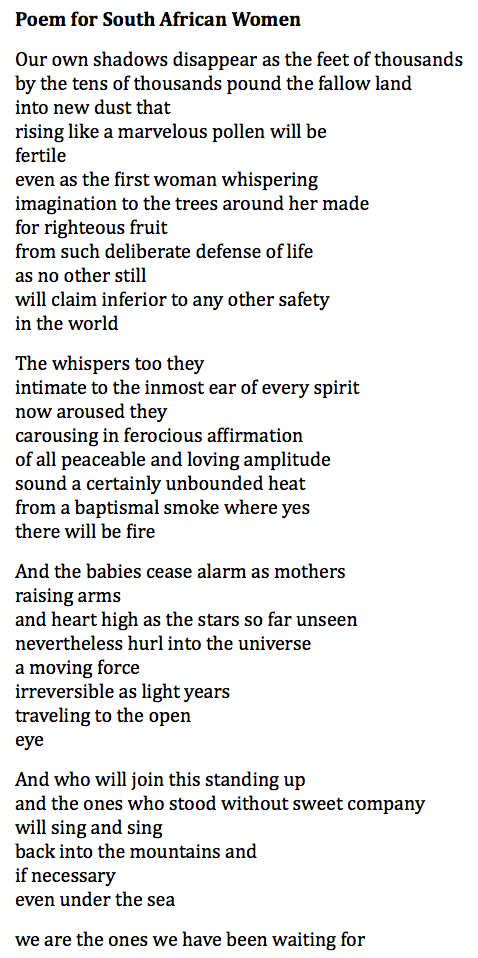

Perspective and Impact on the World

This is the type of question that Jordan would have tried to answer within one of her poems, however, her writing was not limited. She did not limit herself to writing about the negative things of the world nor did she only write about the African American community and the injustices of the world. Yes, she wanted her writings to mean something and to have an impact on the community in which she lived in and the world as a whole. It is for this reason that she tackled such topics as 9/11, police brutality, sexual assault, government scandals and acts of corruption, she wrote about positive things as well. However, she should never be mistake for simply another “angry black woman” who used her poems, books, essays, etc. to let out her frustration. Instead she should be viewed as one who used her platform to make an impact by glorifying love, uplifting black men and women, teaching the youth, and empowering the African American’s experiencing the daily struggles of life. There is so much more than anger to be seen within her poems.

Poems in the Key of Love

One of June Jordan’s more famous books, Haruko/Love Poems was simply a collection of love poems that she had written over the span of twenty-two years.[9] In one of her poems she eloquently wrote about not only love, but also procreation.

“Little moves on sight /blinded by histories /as trivial or expansive /as the rain /seducing light /into a blurred excitement /Then /she opens /all of one eye... she who sees /she frees each of these /beggarly events /cleansing them /of dust and other death.”[10]

June Jordan collaborative community project in Harlem, NYC. July 2002. Brett Cook

This poem alludes to two lovers who are joining to “cleanse them [selves] of death”. They are cleansing themselves of death by making sure they continue to live through the legacy of their children. Which was also something that Jordan believed was essential; the legacy of children. It is for this reason that she wrote many books dedicated to young readers and edited the poems of young writers. In the book Soulscript: A Collection of Classic African American Poetry, she edited the works of young authors. The contributors to this particular book wrote though provoking pieces about experiences that should be well beyond their years. Yet they write about them so eloquently.

One of my personal favorites within this book is entitled Monument in Black.[11] It sheds some light on the differences between races while emphasizing the blood sweat and tears that African Americans have put into this country and into the world, without much recognition. However, she does it through acknowledging the “monuments” that whites have achieved or at least that they are praised for. The message of the overall book is that young authors should have a voice as well since the collection of poems were all produced by young adults.

While this book is only edited by Jordan, it is not the only book that she published for the youth. She wrote Kimako’s Story, Who Look at Me, New Life: New Room and many more.

June Jordan wrote many impactful and important pieces of work.She was an educated African American female who took on the roles of mother, author, and political activist. Her books and poems were a place where these roles could merge together or be non-existent altogether. Jordan’s dedication and style of writing was one that cannot be mimicked and one that is missed. However, due to her impact on her community, her work and legacy will continue, especially since many of her writings are still relevant to the world that we live in today. This exhibit was dedicated to the life and work of June Jordan because she dedicated her life and work to all of us.

Sources

[1] Jordan, June. Civil Wars: Selected Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, 1981, 4-5.

[2] Jordan, June. Collected Poems of June Jordan. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2005.

[3] Jordan, June. Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood. Boston: Basic Civitas Books, 1999.

[4] Jordan, 2005.

[5] Dinitia Smith, June Jordan, 65, Poet and Political Activist, (The New York Times, June 2002).

[6] Jordan, June. "Poem about Police Violence." Mr. Africa Poetry.

[7] Jordan, June. Some Changes.New York City: Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Jordan, June. Haruko/Love Poems. New York City: Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

[10] Ibid., 3.

[11] Howard, Vanessa. Soulscript: A Collection of Classic African American Poetry. New York: Random House Inc., 1970.

Anna Strong is a 2017 graduate of Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. During her studies in English literature, she interned with America’s Black Holocaust Museum. However, she was particularly interested in African American literature and feminism, which led her to research and publish two pieces of work about these in Marquette University’s electronic publications. She is now greatly looking forward to continuing her education within this field and in law.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

Good article Ms Strong. Very well written and informative.