The Freedmen of Wisconsin

Share

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Gregory Bond, PhD

Re-posted from the New York Times Disunion Series, December 22, 2013 (Disunion follows the Civil War as it unfolded.)

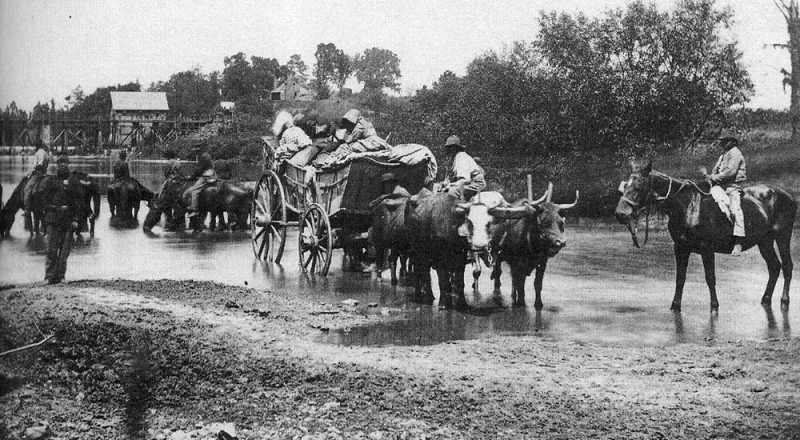

"Contrabands": Runaway slaves in Virginia working for the 13th Massachusetts Infantry.

In the summer of 1862, a 31-year-old slave named Samuel Mathews and his family freed themselves by escaping from their plantation in Franklin County, Alabama. With the army of Union General William Rosecrans nearby, local Confederates had been talking of impressing SamuelMathews into service as a cook. Unwilling to serve the rebel army, Samuel, his 25-year-old wife, Sarah, their 8-year-old son, Richard, and their 7-year-old daughter, Ellen, snuck away to a Union Army camp in nearby Tuscumbia, in the northwest corner of the state. But it was only the first step in their journey to freedom, which would last eight months and finish 700 miles north in the unlikely locale of rural Dodge County, Wisconsin.

Because of political and military decisions early in the war that classified escaped slaves as “contraband” of war, not to be returned to their owners, thousands of enslaved blacks flocked to the relative safety of Union lines; many then made their way north. The Eighth Wisconsin Infantry Regiment participated in the occupation of Tuscumbia, which is where the Mathews family may have first heard about the Badger State. One infantryman took note of the large number of “contrabands” in Tuscumbia and explained to The Janesville Gazette: “The negroes are deserting their masters by hundreds” and “thank God the time has about come when all such folks can claim freedom by just coming into our lines.”

While every former slave had his or her own story of emancipation, the Mathews family saga sheds a light on the often difficult path taken by tens of thousands of people after taking their first steps to freedom – and the changes they brought to the communities where they landed.

"Contrabands": During the Civil War, thousands of slaves escaped their owners in the South by getting to Union Army camps. Thus freed, many continued on to settle in the North.

In early September, the Union Army decamped from Tuscumbia and marched to Mississippi. The African-American refugees accompanied the Yankees, and a soldier from the Eighth Wisconsin wrote that the scene “will forever live in my memory.” In the front, he explained, “moved the Army of the Union and of Freedom” and “in the rear came the army of contrabands, of all ages, sexes, and shades of complexion.” The soldier concluded: “There was to me something strangely sublime in the spectacle of these thousands of human beings fleeing from bondage to freedom.”

The Mathews family was among this “army of contrabands,” but a Confederate counterattack at Iuka, Mississippi, nearly separated them. Years later, Richard Mathews recalled “his fright and terror when he hid in a hollow tree with his baby sister” during the Battle of Iuka, “wondering if he would ever be united with his parents.” Fortunately, all four family members survived the battle.

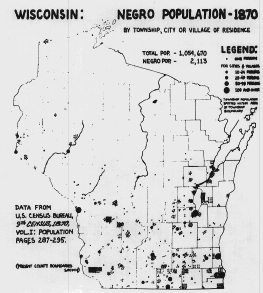

Black settlements in Wisconsin

By the spring of 1863, the Mathews family had traveled north to a Union army contraband camp in Cairo, Ilinois., that was commanded by the Reverend John B. Rogers, a Baptist minister and chaplain to the 14th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. Writing in his memoir, “War Pictures,” Rogers praised the refugees’ hard work and desire for religious and educational instruction. “Old and young come together,” he explained in a letter to the Quaker abolitionist Levi P. Coffin. “They are seen all about after school hours, with books in hand, learning their lessons. May we hope, my dear brother, that from this small beginning there may be great and important results growing to bless the colored race.”

While the Mathews family enjoyed their freedom in Cairo, a group of farmers from the southeast Wisconsin town of Trenton struggled with wartime manpower shortages. The area was staunchly Republican, and as a local newspaper explained, a group of “Union and liberty-loving citizens” decided to conduct “an experiment” by importing former slaves to ease their labor problem.

The leaders of the group – Edison P. Cady, a Baptist deacon, Quartus H. Barron, a representative from Dodge County in the Wisconsin Assembly, and Xury Whiting, a substantial landowner – contacted a freedmen’s aid society and were probably soon directly in touch with Reverend Rogers in Cairo. Rogers and the Trenton farmers were all active Baptists, and the year before, Rogers had arranged for the resettlement of 75 freedmen to his hometown of Fond du Lac, 25 miles northeast of Trenton.

Cady traveled to Cairo and found three dozen refugees, including Samuel and Sarah Mathews and their children, eager to make a new life in Wisconsin. Joining the Mathews family were James and Helen Prebbles, who had escaped from their owner in Arkansas, and a number of refugees from Kentucky, including Hayden Netter, 26, and Serisa Jennie Dobner, 20. On April 8, 1863, Cady arrived by train back in Dodge County with 39 African-Americans.

Not everybody in Dodge County was happy with the settlers, however. The Beaver Dam Argus, a Democratic newspaper, blasted the arrival of the “Black Republicans.” “There is an ‘irrepressible conflict’ between free white labor and free black labor,” The Argus declared, and “white laborers may as well prepare to take a ‘back seat.’” The Argus boldly claimed that “these negroes … will undergo more hardships and for less pay than they ever did with their owners in the South.”

Not everybody in Dodge County was happy with the settlers, however. The Beaver Dam Argus, a Democratic newspaper, blasted the arrival of the “Black Republicans.” “There is an ‘irrepressible conflict’ between free white labor and free black labor,” The Argus declared, and “white laborers may as well prepare to take a ‘back seat.’” The Argus boldly claimed that “these negroes … will undergo more hardships and for less pay than they ever did with their owners in the South.”

Despite such dire predictions, the former slaves and their white employers settled into new lives. The Mathews family worked on the farm of Quartus H. Barron, and when their second son was born a year later, they named him Henry Quartus Mathews to honor their benefactor. The Prebbles lived and worked on Xury Whiting’s farm, and other farmers in Trenton provided accommodations to the rest of the settlers. Soon after her arrival, Serisa Dobner married George W. Newsom, the son of one of the few free blacks already in the area.

Hayden Netter had little time to enjoy Wisconsin and was drafted seven months after his arrival. In November 1863, he joined Company E of the Wisconsin First Infantry Regiment, becoming one of the few African-American soldiers to serve in otherwise white units. Newlywed George Newsom was drafted a year later and served in the 67th Regiment of the United States Colored Infantry.

When the Army drafted another local African-American, the Unionist Dodge County Citizen goaded its political rivals. “Here is an excellent opportunity,” the Republican newspaper wrote,

for the “copperheads who think it is such a dreadful thing to make soldiers of colored men, to step forward and go as his substitute.” No Democrats accepted the offer. Instead, The Argus continued its campaign against the black settlers, accusing Trenton’s “mock philanthropists” of “shamefully” abusing the newcomers and alleged that the freedmen “would gladly return to their former comfortable quarters in the South.”

for the “copperheads who think it is such a dreadful thing to make soldiers of colored men, to step forward and go as his substitute.” No Democrats accepted the offer. Instead, The Argus continued its campaign against the black settlers, accusing Trenton’s “mock philanthropists” of “shamefully” abusing the newcomers and alleged that the freedmen “would gladly return to their former comfortable quarters in the South.”

Netter remained in the Army for the duration of the war, serving uneventfully in two other white Wisconsin regiments. George Newsom was not as fortunate and died of “typhoid malarial fever” in Morganza, Louisiana, on April 7, 1865, a week before the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Newsom left behind his 22-year-old widow and 1-year-old son in Wisconsin.

In the summer of 1865, Netter returned to Dodge County to find a thriving black community. After living on rural farms for three years, many of the immigrants had saved enough money to make it on their own, belying The Beaver Dam Argus’s contention that the Trenton farmers had “used these negroes worse than they were ever used in the South.” In April 1865, Prebbles was the first African-American to purchase property in the nearby village of Fox Lake, and six months later, the Mathews family bought the house next door. By 1870, Netter, who had married the widowed Serisa Dobner Newsom, and two other black families also owned property in Fox Lake.

John Green, father of Thomas and Hardy Green, on the cover of Zachary Cooper's book.

The black and white residents of the village seemed to get along well. The African-American men cast their ballots once the Wisconsin Supreme Court re-affirmed black suffrage in 1866, and black children attended school with their white neighbors. Prebbles served as the Fox Lake streets commissioner in the late 1870s, and Prebbles and Samuel Mathews often worked for the village. The Fox Lake Representative captured the local progressive political attitude with its masthead: “Equal Rights for All Men and Women – White or Black.”

The community reached its peak about 20 years after the Civil War. The 1880 census recorded 66 African-Americans in Fox Lake (out of a total population of 956) and 10 more nearby black residents, or 6.9 percent of the village’s population, one of the highest shares in the state. In that same census, Madison, with a population 10 times greater, counted only 63 African-Americans. The vibrant community supported one of Wisconsin’s earliest congregations of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, when Sarah Mathews and James Prebbles received a charter in 1872.

As the 19th century came to a close, however, the community splintered. Rising white resistance to social contact between the races and the mechanization of farm work encouraged many members of the second generation of Fox Lake’s “Negro Colony” to move away for better opportunities in places like Milwaukee and Chicago.

The black population dwindled. In 1884, the Netter family moved away; in 1896, Samuel Mathews died, and three years later James Prebbles died. Sarah Mathews’s death in 1914 marked the passing of the original generation of adult settlers. In about 1898, the remaining community members closed the A.M.E. Zion Church.

Although the memory of the local black community faded as the descendants of the original immigrants left town, settlements like the Fox Lake Negro Colony remain an important part of the Civil War’s legacy. In countless neighborhoods, towns and cities, sympathetic whites worked together with former slaves to make sense of their new world and to adapt to the reality of African-American freedom and citizenship.

For more information about the Black experience and history in Wisconsin, please visit the Wisconsin Black Historical Society.

Sources:

Unpublished manuscripts, biographical material and newspapers clippings, Harriet O’Connell Local History Room, Fox Lake Public Library; Beaver Dam Daily Citizen, Nov. 17, 1932; Newspaper clippings, E.B. Quiner Scrapbooks, vol. 4, Wisconsin Historical Society; Beaver Dam Daily Citizen, Nov. 17, 1932; J.B. Rogers, “War Pictures”; Levi Coffin, “Reminiscences of Levi Coffin“; Dodge County Citizen, April 16, 1863, and March 31, 1864; Sally Albertz, “Fond du Lac’s Black Community and Their Church”; Roster of Wisconsin Volunteers, War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865; George W. Nusom [sic] military service record, National Archives and Records Administration; Dodge County Citizen, Nov. 26, 1863; Beaver Dam Argus, April 15, 1863, and March 23 and April 13, 1864; Fox Lake Representative May 7, 1875; 1860, 1870, 1880, and 1900 United Stated Federal Census, Wisconsin; 1875, 1885, 1895, and 1905 Wisconsin State Census.

Gregory Bond, who received his doctorate in American history from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is currently researching the history of the Fox Lake Negro Colony.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

very good website

This is great. I loved your site and the work you have done from one historian to another. Keep up the good work The more who write the less chance we have of being forgotten. It was sites like this that inspired me to become a historian.

Hi my name is Terra Bautista. I have recently started researching my ancestry and have come to learn that I am a descendant of Samuel and Sarah Mathews. I would appreciate any communication that would help me learn more or understand more of the history. I would also like to share any additional information that might be helpful to you and your museum.

Terra, I wish we had the human and materials resources to help you in your search for more information about your ancestors. We hope you will find some of the answers about history that you seek here in this virtual museum and through its links to other resources. A great place for you to visit, once the pandemic is past, would be the WI Black Historical Society in Milwaukee WI. There you would find a wealth of information about Black Wisconsinites. We would also welcome any additional information you have to share with us.

Hi,

They are my 2nd great grandparents. I don’t have a lot of information, but I will share what I can.