The Kiss

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Sara Rimer, Eji

On October 28, 1958, two Black children were arrested and jailed for months after a white girl kissed them on the cheek.

A bright, warm afternoon in late October 1958, in rural Monroe, North Carolina: two Black children, nine-year-old James Hanover Thompson and his eight-year-old friend David “Fuzzy” Simpson, were playing with a group of white boys and girls in the yard next to one of the white children’s homes. Jim Crow laws were rigidly enforced at the time, but it was not unusual for Black and white children to play together when their separate, segregated schools let out for the day. They knew each other. The mothers of the Black children cooked and cleaned for the mothers of the white children.

As afternoon gave way to evening that day, October 28, and some of the children left, a kissing game began. One of the white girls, seven-year-old Sissy Sutton, kissed first David on the cheek, and then James, before heading home. Retrieving their wagons, which held a stash of empty bottles they hoped to sell, the two friends walked toward the center of town. They had no way of knowing they’d done anything wrong, and that white Monroe was about to severely punish them, and their families—for a kiss.

Sissy Sutton mentioned the kiss to her parents when she got home. James’s mother had worked for Sissy’s mother; his grandmother had worked for Sissy’s grandmother. Reportedly in hysterics and threatening to kill James, Sissy’s mother notified police. Rumors raced through the white community. Sissy’s father grabbed his shotgun and, joined by a mob threatening a lynching, he crossed the railroad tracks that divided Monroe’s white and Black neighborhoods. The Thompsons’ house was dark. The mob would have killed them if the police hadn’t gotten there first, Mr. Thompson told EJI, recalling “…they would have shot us. They was mad, they was gonna kill us.” James’s mother, Evelyn Thompson, would also tell a reporter months later that “some white people in Monroe” had warned her “that my family would be killed if I didn’t get out of town.”

James and David were pulling their wagons when police accosted them, with guns drawn. Shouting racial epithets and calling them “little rapists,” police handcuffed the boys and shoved them into a patrol car. “When we got down to the police station, we understood that they said we had raped a little white girl,” James Thompson would recall more than half a century later. “They took us down in the bottom of the police station to a cell … They started beating us, they were beating us to our body, you know? They didn’t beat us to the face where nobody could see it. They just punched us all in the stomach and back and legs. We couldn’t understand why grown people was beating us up, but we didn’t have nobody to defend us. We was hollering and screaming. We thought they were going to kill us.” Their cries were only met with “shut up back there!” Mr. Thompson told EJI.

For the next six days they were kept locked up and barred from seeing their parents. Police entered their cell on Halloween, pretending to be Klansmen. “These men came with sheets over their heads,” Mr. Thompson would recall later. “They said they were going to hang us, lynch us. I was crying. I was scared to death.”

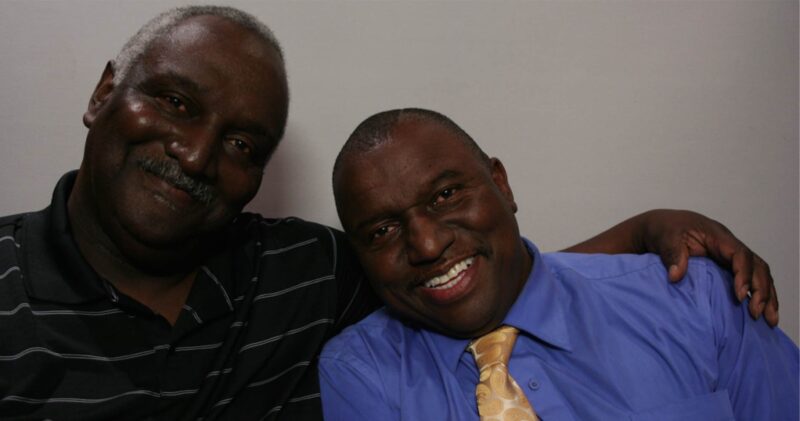

So began the infamous “kissing case,” as it came to be called, a case that shined an international spotlight on the bigotry and racial injustice in the South. The lives of James Thompson and David Simpson and their families were shattered and the entire Black community was traumatized, but as the spotlight shifted, with the exception of a television interview with Oprah Winfrey in 1993 and a 2011 interview for StoryCorps and NPR, the kissing case all but disappeared from public view.

EJI details what the children endured, the trial, and the aftermath.

Stories like these are all too common when it comes to lynching.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.