The Long Afterlife of a Lynching

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Karen Branan

Karen Branan searched for the truth about her family's involvement in the lynching of four people in Georgia in 1912.

The old man was waiting for me when I arrived. He didn’t know I was coming nor did I; it just turned out that way. I was in Harris County, Ga., my ancestors’ home, in 1995, hoping to find some elders who’d remember a lynching eighty-three years ago. I doubted I’d find any and, if I did, doubted they’d talk about it but I was quickly stunned to discover there were many who’d been small children in 1912 when a woman and three men were lynched and they were more than willing to talk about what they’d seen and heard.

The Lynching

The old man’s name was Clyde Slayton. He was sitting in a rocker on the plain pine board porch of the cabin he’d lived in all his life. He was a small boy on that midnight of Jan. 22, 1912, when a mob of men snatched Dusky Crutchfield, John Moore, Gene Harrington, and Burrell Hardaway out of their jail cells in Hamilton, Ga., and marched them to a water oak beside the outdoor baptismal font of the black Friendship Baptist Church.

They were being held on suspicion of the murder of the sheriff’s nephew. The mob had tried to take them a week earlier as the sheriff was carrying them to jail but he’d talked them out of it, promised a speedy trial, that “justice would be done.” He was new to the job and didn’t want a lynching. It was getting harder in 1912 for sheriffs to simply turn black prisoners over to mobs – some blacks were suing, more progressive white lawmakers were passing laws against it, laws rarely enforced. The local judge was a fierce anti-lynching man. So the mob promised to stand by and the sheriff got the judge to schedule a special trial but soon thereafter his case against the four fell apart. The mob moved in and the dark deed was done. Five hundred shots fired at midnight. Bodies left hanging all the next day.

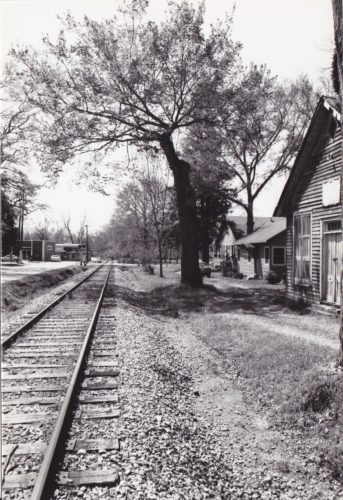

The lynching took place by the outdoor baptismal font here, at the Friendship Baptist Church in Hamilton, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Deborah Dawson

My Family's Involvement

The sheriff was my great-grandfather. His deputy was my grandfather. The mob was made up of many of my kinfolk. “Parties unknown,” the grand jury declared, hewing to that ancient script so scrupulously followed by grand juries all over the South for more than a century. I later learned the youngest man on that tree, Johnie Moore, was kin to me from slavery. I’d learn a lot more about black-white kinship in Harris County before it was all over.

“There were a lot of bad people around here back then,” Slayton told me after removing a wad of Red Man tobacco from his jaw and placing it gingerly on a piece of cheesecloth stretched across a McDonald’s Big Slurp cup. I’d been sent down to see Slayton by C.D. Marshall, a black man I’d run across up the road. Marshall was hoeing the corn patch next to his cabin, which had been there since slavery, he told me, the last of its kind in the county. He’d already told me ‘those four folks was innocent.’ I didn’t mention this to Slayton – who was white and turned out to be a cousin on my mother’s side – but he said the same thing. He knew who’d killed the sheriff’s nephew. “It was a white man,’’ he confided. “I just thought of his name last night, but now I can’t remember it.”

Curses and Ghosts: The Lynching's Long Aftermath

It was like this with numerous people I spoke with on my journey. No one knew I was coming. I had no idea who I’d interview. I just drove around country roads looking for old folks on porches, in gardens or corn patches. “Confessed on his deathbed. Sometime in the 30s.” Slayton tried to remember the name of the white man who’d killed my cousin Norman and for whose murder the four had been lynched, but couldn’t. Like a lot of the folks I talked with he spoke of other killings, later killings. White men killing white men. I wasn’t sure at first why they brought these up. It was a while before I realized they were part of the 1912 lynching’s long aftermath. “Every man in the mob died with his boots on,” numerous people told me, black and white.

A curse fell over the county. Long hours of research later, I’d learn that many of the wives and children of folks in the mob or folks in authority who let it happen died suddenly or in freak accidents after that midnight of horror. My great grandfather, the sheriff’s, daughter, only 19 and a new mother, felled by typhoid fever. Judge Williams, my paternal great grandfather’s brother, lost a son and a young granddaughter overnight it seemed. Another branch of the family lost young ones. A young man stomped to death by a mule, a leading citizen stricken with indigestion and dead on the sidewalk in a flash just before Christmas. It went like that into the 20s, the killings and the freak accidents. My great uncle Dock’s head “beat to jelly” in a gambling row, my uncle Worth’s head crushed beyond recognition in an auto accident. Before it was all over, sixteen of the men said to have been in the lynch mob had been murdered by other men said to have been in the lynch mob. The last was shot to death in 1929 by a black man in self-defense. He’d gone after the man with a gun, thinking he was making the howling noises outside his window, noises long believed to have been made by the ghost of the woman who was lynched. “Vengeance is mine, sayeth the Lord,” old folks, black and white, murmured, shaking their heads slowly, each time they heard of another, over those long years slow justice was being exacted.

Painful Memories Still Fresh

Despite my fears the lynching would have been forgotten, I found that old memories remained fresh. As if recalling an event that very week, the Fort sisters, Mary and Edna, retired white schoolteachers, launched into a painful description, their faces as stricken as they must have been when, as children, they lay quaking beneath their covers, the terrified shrieks of Dusky Crutchfield ricocheting around their bedroom as she was dragged past the window

It’s been twenty years since I made those rounds in Harris County, Georgia, but I think of those people still. Black and white, they expressed deep sorrow for the four innocent people and the heinous way they died.

Why didn’t this ever come to light? Why didn’t anyone ever make public the truth behind this 1912 lynching and the ways it affected them all?

It kept many African Americans scared all their lives. It kept a lot of the decent white ones ashamed, deeply ashamed, of the fathers and the neighbors who committed the crime. It cursed the county and kept many blacks and whites at a distance from one another -- a distance which, for many, remains.

Telling the Truth

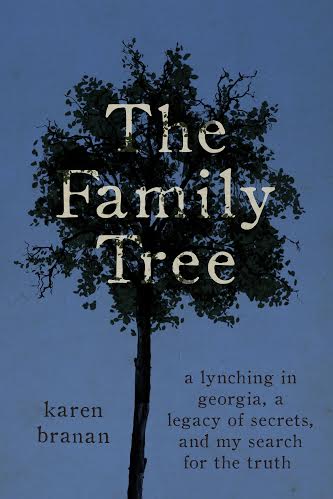

I like to think that I am continuing the work that some of them began. I like to think that I am telling truths that some of them wanted to tell and for whatever reason couldn’t or wouldn’t. In The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, A Legacy of Secrets, My Search for the Truth (Simon & Schuster, Jan. 2016), I tell the story these “Ancient Mariners,” as I call them, told me, of how an innocent woman and four innocent men were wrongly murdered to cover up the murder of a white man by a white man and to cover up the inter-racial night-time lifestyles of some of the county’s most prominent white men.

I like to think that I am continuing the work that some of them began. I like to think that I am telling truths that some of them wanted to tell and for whatever reason couldn’t or wouldn’t. In The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, A Legacy of Secrets, My Search for the Truth (Simon & Schuster, Jan. 2016), I tell the story these “Ancient Mariners,” as I call them, told me, of how an innocent woman and four innocent men were wrongly murdered to cover up the murder of a white man by a white man and to cover up the inter-racial night-time lifestyles of some of the county’s most prominent white men.

My prayer is that bringing these long-festering secrets into the sunlight for honest discussion among black and white people will reduce the distance between us.

Simon & Schuster synopsis

In the tradition of Slaves in the Family, the provocative true account of the hanging of four black people by a white lynch mob in 1912—written by the great-granddaughter of the sheriff charged with protecting them.

Harris County, Georgia, 1912. A white man, the beloved nephew of the county sheriff, is shot dead on the porch of a black woman. Days later, the sheriff sanctions the lynching of a black woman and three black men, all of them innocent. For Karen Branan, the great-granddaughter of that sheriff, this isn’t just history, this is family history.

Branan spent nearly twenty years combing through diaries and letters, hunting for clues in libraries and archives throughout the United States, and interviewing community elders to piece together the events and motives that led a group of people to murder four of their fellow citizens in such a brutal public display. Her research revealed surprising new insights into the day-to-day reality of race relations in the Jim Crow–era South, but what she ultimately discovered was far more personal. As she dug into the past, Branan was forced to confront her own deep-rooted beliefs surrounding race and family, a process that came to a head when Branan learned a shocking truth: she is related not only to the sheriff, but also to one of the four who were murdered. Both identities—perpetrator and victim—are her inheritance to bear.

A gripping story of privilege and power, anger, and atonement, The Family Tree transports readers to a small Southern town steeped in racial tension and bound by powerful family ties. Branan takes us back in time to the Civil War, demonstrating how plantation politics and the Lost Cause movement set the stage for the fiery racial dynamics of the twentieth century, delving into the prevalence of mob rule, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the role of miscegenation in an unceasing cycle of bigotry.

Through all of this, what emerges is a searing examination of the violence that occurred on that awful day in 1912—the echoes of which still resound today—and the knowledge that it is only through facing our ugliest truths that we can move forward to a place of understanding.

More about the book here.

Buy the book at online book retailers: Amazon and Barnes and Noble

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

I am 71 years old. I was born and raised in Harris County, Hamilton, Ga. I was actually baptized in that baptismal pool at Friendship Baptist Church near which that infamous Water Oak stood. Never heard of this travesty until now. I left when I was 16 years old.