This Date in History: The Zong Massacre Begins

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From the African American Registry

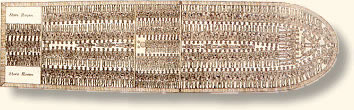

On this date, in 1781, the Zong massacre began. This was a mass killing (at sea) of more than 130 enslaved Black Africans by the crew of the British slave ship Zong during the Middle Passage.

Owned by England, when the Zong sailed from Accra with 442 slaves on August 18, 1781, it had taken on more than twice the number of people it could safely transport. In the 1780s, British-built ships typically carried 1.75 slaves per ton of the ship’s capacity; on the Zong, the ratio was 4.0 per ton. A British slave ship of the period would carry around 193 slaves; it was unusual for a ship of the Zong‘s small size to carry so many. After taking on drinking water at São Tomé, the Zong began its voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to Jamaica on September 6th. On November 18, the ship neared Tobago in the Caribbean without stopping for water supplies.

It is unclear who, if anyone, was in charge of the ship at the time; Luke Collingwood, James Kelsall, and Robert Stubbs were in decision-making positions. According to historian James Walvin, the breakdown in command explains the navigational errors and the absence of checks on drinking water supplies. On November 28, the crew sighted Jamaica at a distance of 27 nautical miles but misidentified it as the French colony of Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola. Zong continued on its westward course, leaving Jamaica behind. This mistake was recognized only after the ship was 300 miles (480 km) from the island. Overcrowding, malnutrition, accidents, and disease had already killed several mariners and approximately 62 Africans.

James Kelsall later claimed that there was only four days’ water on the ship when the navigational error was discovered, and Jamaica was still 10–13 sailing days away. If the enslaved people died onshore, the Liverpool ship-owners would have had no redress from their insurers. Similarly, insurance could not be claimed if the enslaved people died a “natural death” (as the contemporary term put it) at sea. If some enslaved people were thrown overboard to save the rest of the “cargo” or the ship, then a claim could be made under “general average.” (This principle holds that a captain who jettisons part of his cargo to save the rest can claim for the loss from his insurers.) The ship’s insurance covered the loss of enslaved people at £30 per person.

In total, 142 Africans were killed when the ship reached Jamaica. The King’s Bench trial account reports that one enslaved person managed to climb back onto the ship after being thrown into the water. The crew claimed that the enslaved people had been scrapped because the ship did not have enough water to keep all the enslaved people alive for the rest of the voyage. This claim was later disputed. The Gregson slave-trading syndicate, based in Liverpool, owned the ship. They had taken out insurance on the lives of the enslaved people as cargo.

Learn more about The Middle Passage.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.