Voting Rights in Wisconsin and the Impact of Freedom Schools in Milwaukee

Share

Risking Everything: The Fight for Black Voting Rights

Explore Our Galleries

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Adamali De La Cruz

Editor: Robert S. Smith, PhD

Black Suffrage in Wisconsin

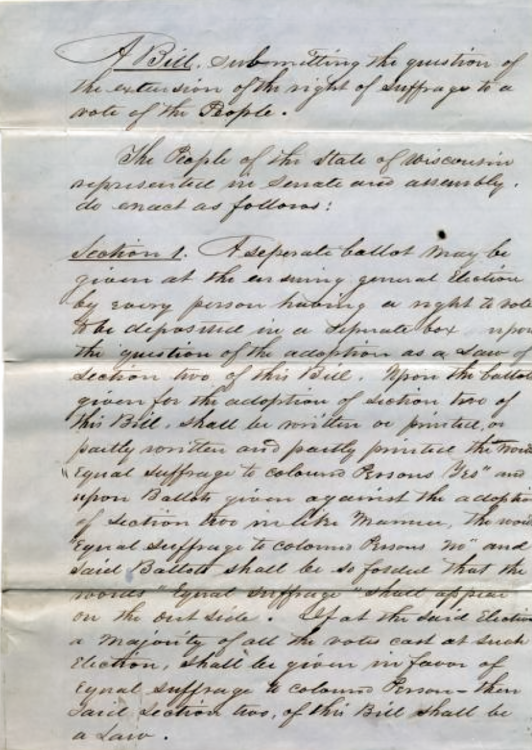

1849 Assembly Bill 122 which established that African American men were allowed to vote and was reaffirmed in the 1866 Wisconsin Supreme Court Case Gillespie v. Palmer and others. Wisconsin Historical Society.

The very first election in Milwaukee happened in 1835. Milwaukee was just emerging as a growing settlement and needed to appoint a mayor. As one of the earliest settlers, Joe Oliver, a Black cook for Solomon Juneau, was able to participate in the historic decision making process. While legally he did not have the right to vote as an African American, due to his relationship with many prominent settlers his vote was counted.1 This 1835 election is a unique situation where one African American’s voice was included.

Chronologically, it was in 1849 when a referendum was passed granting African Americans the right to vote. However, like in many other parts of the United States, Wisconsin denied African Americans their political rights and since the Black population was so low it was difficult to organize. So while the 1849 referendum gave Black men suffrage it was not enforced. It was not until 1865 when the actions of Ezekiel Gillespie began a series of events that resulted in the 1866 Wisconsin Supreme Court case Gillespie v. Palmer and others which reaffirmed the right to vote for African American men in Wisconsin.2

Ezekiel Gillespie and the Board of Inspectors

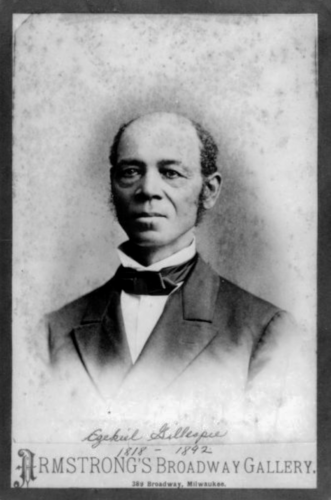

Head and shoulders portrait of Ezekiel Gillespie. Gillespie was born in 1818 and died March 31, 1892. In 1866, Milwaukee's Ezekiel Gillespie successfully sued for the right to vote. Wisconsin Historical Society.

In 1865 Gillespie attempted to register to vote ahead of the gubernatorial election and was refused. Even though he was refused, he still attempted to vote in that year’s gubernatorial election anyway and again was refused. In response to the denial of his voting rights, Gillespie filed a lawsuit against the Board of Inspectors. This suit was supported by Sherman Booth, a prominent newspaper editor and abolitionist, and Booth’s lawyer, Byron Paine.3 Both Paine and Booth were well known in the state of Wisconsin because of their involvement in a Wisconsin Supreme Court case that declared the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 unconstitutional.4 The Gillespie case ended up before the Wisconsin Supreme Court by 1866 where a unanimous vote granted that African American men could legally vote.

Freedom Schools from Mississippi to Wisconsin

The Mississippi Freedom Project at its conception had one major goal which “aimed at the overthrow of the existing political structures of the state [of Mississippi]...to make way for new ones.”6 In order to achieve this goal there were a few main tactics:

1) to run a large voter registration program in order to garner evidence to challenge voter suppression tactics,

2) to establish a political party known as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and

3) to better educate and instill pride in young black children through the formation of Freedom Schools.

The concept of the Freedom School was a particularly revolutionary idea because the idea that education could shape society's values in a negative way was not something many considered. This is something that was highlighted in a prospectus by Charlie Cobb, a member of the Student’s Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was the inspiration for the Freedom School component of the Mississippi Freedom Party.7

Protesters marching against school segregation in Milwaukee 1964. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Indeed, the impact of Freedom Schools was felt not just in Mississippi, but also in Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Freedom Schools were launched by the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC) under the direction of Lloyd Barbee. Similar to what was happening in Mississippi, Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) refused to commit to full integration as was required by the landmark Supreme Court Case, Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In response to this MUSIC led a series of boycotts on MPS in 1964, 1965, and 1966 in order to pressure the district to make efforts to end public school segregation and intact busing.8

The reality of education for Black children in Milwaukee was one of segregation and inequity, much like in the Jim Crow South. Despite segregation having been declared unconstitutional, MPS made very little effort to integrate schools and maintained de facto segregation. Intact bussing was one of the main points of contention during the MPS school boycotts because rather than integrating all students, classes of Black students would report to their regular overcrowded schools and then be bussed to a receiving mostly white school, to then have classes together rather than being incorporated into the receiving schools classrooms.9 This gave the illusion of integration because physically Black and white students occupied the same building while maintaining the segregation of classrooms, lunch periods, and bussing.

Boycotts were held in 1964, 1965, and 1966. This image shows Father Groppi, a notable Milwaukee pastor and civil rights activist, with children during the 1965 MPS boycott. Wisconsin Historical Society.

When student-led boycotts were conducted to demand equal education to Black children in Milwaukee, Freedom Schools were held in churches and community centers in the northside of the city. Many of the educators in these Freedom Schools were local volunteers, much like those of the Mississippi Freedom Schools. Despite the pressure that the MUSIC sponsored boycott placed on MPS for over a year, the school board refused to do anything meaningfully to begin the process of integration. In response to this lack of action, attorney Lloyd Barbee filed a federal lawsuit titled Amos et al. v. Board of School Directors of the City of Milwaukee.10

Attorney Lloyd Barbee, head of the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee. Wisconsin Historical Society.

The allegations made in the lawsuit accused MPS of maintaining de facto segregation through various policies such as the neighborhood school policy. MPS responded that it was in fact the housing patterns that segregated the schools and indeed much of the city of Milwaukee was segregated due to factors such as redlining and other issues.11 However, Barbee maintained that MPS was further deepening segregation and used the research that was compiled by MUSIC showing that MPS was not keeping track of racial statistics until 1964 and that Black teachers were disproportionately assigned to teach in overcrowded schools with predominantly Black students. The efforts of Lloyd Barbee and MUSIC were successful in 1976 when federal Judge John Reynolds ordered MPS to develop a plan for school integration.12

Click here to view more Risking Everything: The Fight For Black Voting Rights.

Endnotes

1Teran Powell, “A Look at Milwaukee’s Earliest Black Settlers,” WUWM 89.7 Milwaukee’s NPR, July 29, 2022, https://www.wuwm.com/2022-07-29/a-look-at-milwaukees-early-black-settlers.

2“Gillespie V. Palmer and Others,” Wisconsin Court System, 20 Wis. 544 (1866), https://www.wicourts.gov/courts/supreme/docs/famouscases06.pdf

3John O. Holzhueter, “Ezekiel Gillespie, Lost and Found,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, 60, no. 3 (Spring 1977): 182. https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/wmh/id/34084

4“In Re: Booth,” Wisconsin Court System, 3 Wis. 1 (1854), https://www.wicourts.gov/courts/supreme/docs/famouscases01.pdf

5Risking Everything ebook, chapter 2

6Risking Everything ebook, chapter 5

7“Freedom Schools,” March on Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, accessed Sept. 20, 2024, https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/keyterms/freedom-schools/.;

8“Brown v. Board of Education (1954),” National Archives, accessed Sept. 20, 2024, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education.

9“Bussing, Intact,” March on Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, accessed Sept. 20, 2024, https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/keyterms/bussing/

10“Amos et al. v. Board of School Directors of the City of Milwaukee,” March on Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, accessed Sept. 25, 2024, https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/keyterms/amos-et-al-v-board-of-school-dir/.

11Leah Foltman and Malia Jones, “How Redlining Continues To Shape Racial Segregation In Milwaukee,” WisContext, accessed Sept. 25, 2024, https://wiscontext.org/how-redlining-continues-shape-racial-segregation-milwaukee.

12“Amos et al. v. Board of School Directors of the City of Milwaukee,” March on Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, accessed Sept. 25, 2024, https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/keyterms/amos-et-al-v-board-of-school-dir/.

Scholar-Griot, Adamali De La Cruz is the Education and Griot Coordinator at America’s Black Holocaust Museum. She is a graduate of Marquette University's History department with a focus on medieval studies. She joined ABHM as a Griot/Center for Urban Research and Teaching Outreach (CURTO) Intern in 2022 and formally joined the ABHM Ed. Dept in 2023. As the Education and Griot Coordinator, Adamali has developed the Junior Griot Program for high school students, coordinates with volunteers, has assisted in formalizing the college internship program at ABHM, and writing of virtual exhibits and other public history projects that ABHM contributes to.

Editor, Dr. Robert S. Smith is the Harry G. John Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching & Outreach at Marquette University. He serves as ABHM’s Director of Education and Resident Historian. His research and teaching interests include African American history, civil rights history, and exploring the intersections of race and law. Dr. Smith is the author of Black Liberation from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter and Race, Labor & Civil Rights; Griggs v. Duke Power and the Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Prior to joining Marquette University, Dr. Smith served as the Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Inclusion & Engagement and Director of the Cultures & Communities Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And, Rob is the proud father of Henderson Marcellus Smith.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.