War on Drugs – or War on Blacks?

Share

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Reggie Jackson

President Ronald Reagan talks about his drug policies in a March 1987 press conference.

“The mood toward drugs is changing in this country, and the momentum is with us. We're making no excuses for drugs -- hard, soft, or otherwise. Drugs are bad, and we're going after them. As I've said before, we've taken down the surrender flag and run up the battle flag. And we're going to win the war on drugs.” – President Ronald Reagan, October 2, 1982

With these words America’s modern War on Drugs was launched. This war would have many casualties. The war would lead the United States down the path to incarcerate over two million people. State budgets would expand to pay the costs of hundreds of new prisons. The black and Latino communities would lose countless young men to incarceration. By 2015, the Federal government will spend over $25 billion annually to combat drugs.

Tulia, Texas: Watch this film about one small town’s experience with the War on Drugs.

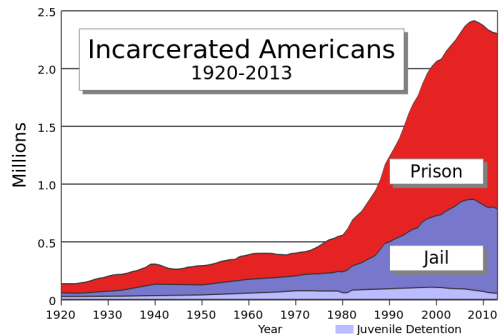

The "War on Drugs" begun by President Reagan in the 1980s resulted in a sudden steep rise in the number of Americans being jailed. The US now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world.

The irony of the War on Drugs being launched in the 1980s is that illicit drug use had been dropping for about a decade. We were essentially beginning to fight a war with an enemy that no one believed existed. In fact, less than 2 percent of the public viewed drugs as the most important issue facing the nation. Prior to this time the federal government played only a small role in crime control. Reagan’s Attorney General, William French Smith recommended a policy shift to deploy a “strong federal law enforcement capacity” in what he called a “highly popular” manner.

This shift led Reagan to fulfill one of his campaign promises, to get tough on crime. He used coded racial language to convince whites to believe that a “human predator” existed. This predator would primarily be young black males. In 1970 Sidney Wilhelm wrote a book titled, Who Needs the Negro? He argued that black labor was no longer necessary to the American economy due to automation and de-industrialization. Blacks would become the enemy in the War on Drugs.

The Willie Horton Ad and the Revolving Door Attack Ads

Prisoners in a Louisiana jail

The Reagan Administration and Congress authorized $125 million to establish regional drug task forces employing over 1,000 FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) and DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) agents along with new federal prosecutors. The FBI drug enforcement budget skyrocketed from $8 million in 1980 to over $95 million four years later. From 1981 until 1991 the DEA antidrug budget increased from $86 million to over a billion dollars. Alongside these increases federal allocations for education and treatment of drug abuse was decimated. The National Institute on Drug Abuse saw its funding slashed from $274 million in 1981 to only $57 million by 1984.

This new emphasis on criminal prosecution of the Drug War led to a huge increase in state and local law enforcement and prosecution. The enforcement of new, more harsh drug laws would be concentrated in poor black communities. These communities were already suffering tremendously due to the major recession of the early 1980’s. Family supporting wages from manufacturing jobs, which drove many blacks into northern communities beginning in the 1950’s, were being shifted overseas. Jobs were difficult to find and in some cases impossible to find. The jobs that were created during this time were mostly in the suburbs, and inaccessible to inner city residents.

An illicit drug market became the replacement labor force. Crack cocaine, became the tool by which this market expanded. In 1984 the Los Angeles Times first reported on the use of cocaine “rocks” in black and Latino neighborhoods. Crack was simply a mixture of powdered cocaine, water and baking soda that was “cooked” to produce smokable “rocks.” By 1986 this new form of cocaine was only found in Los Angeles, New York, Miami and a handful of other big cities.

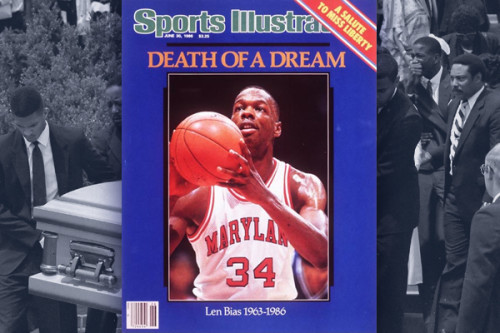

Two professional athletes, Len Bias of the Boston Celtics and Don Rogers of the Cleveland Browns died in June 1986 of what was referred to by the media as “crack related” incidents that were in reality powdered cocaine overdoses. News coverage increased overnight of police raiding “crack houses” and escorting black and Latino males away in handcuffs. In July 1986 the three major networks (ABC, NBC, CBS) showed seventy-four evening news segments on drugs, including over thirty stories on crack. Newspapers around the country produced about one thousand stories about crack leading up to the mid-term congressional elections in November 1986.

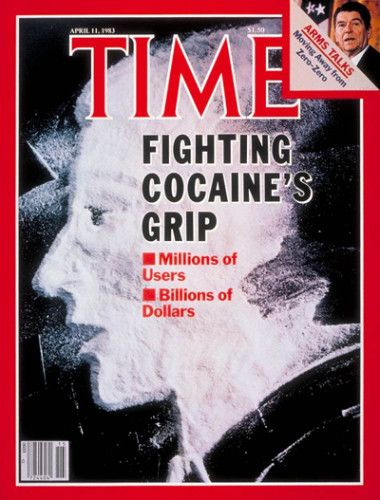

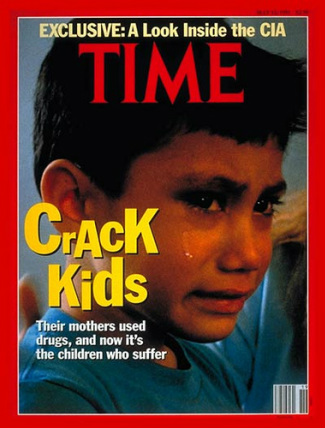

By mid 1986 Newsweek called crack the biggest story since Vietnam and Watergate. Time magazine called it the issue of the year. The “crack epidemic” or “crack plague” became the most common terms to describe the drug. The intense media coverage of crack led the DEA to issue a press release to correct the misperception of crack. They stated, “crack is currently the subject of considerable media attention…The result has been a distortion of the public perception of the extent of crack use as compared to the use of other drugs…it appears to be a secondary rather than primary problem in most areas.”

One of the most incendiary stories related to crack was the so-called “crack babies.” These were babies born to drug using mothers. The hysteria surrounding this phenomenon led to laws being passed to prosecute mothers who tested positive for cocaine. Crack and powdered cocaine are indistinguishable. Therefore there is no way to tell if the mother had used crack or powdered cocaine. Despite the fact that no data was available on supposedly “crack-addicted babies”, the media ran hundreds of stories warning that these children would become menaces to society. Only later did studies prove this to be untrue. The media barely covered this new information.

One of the most incendiary stories related to crack was the so-called “crack babies.” These were babies born to drug using mothers. The hysteria surrounding this phenomenon led to laws being passed to prosecute mothers who tested positive for cocaine. Crack and powdered cocaine are indistinguishable. Therefore there is no way to tell if the mother had used crack or powdered cocaine. Despite the fact that no data was available on supposedly “crack-addicted babies”, the media ran hundreds of stories warning that these children would become menaces to society. Only later did studies prove this to be untrue. The media barely covered this new information.

The intense media scrutiny led Congress to pass the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act. The bill introduced mandatory minimum sentences including a 5-year term for possession of five grams of crack cocaine, while mandating the same sentence for 500 grams of powdered cocaine, a 100:1 ratio. The crack scare died down after the election.

By 1988, crack became an issue again during the election cycle. ABC News reported that crack was a “plague…eating away at the fabric of America.” The rhetoric about crack continued, and led Congress to pass the 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which enhanced drug penalties and led to the Comprehensive Community Substance Abuse Prevention Act of 1989. These Congressional acts led to huge increases in law enforcement budgets. As a result the prison population began to soar. In 1980 there were only 14,100 people in prison or jail for drug offenses. Today there are over a half-million, in increase of 1,100 percent.

The impact of the drug scare would continue during the Clinton administration with the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the largest crime bill in U.S. history. It placed an additional 100,000 new police officers on the street and provided nearly $10 billion funding for prisons. It also eliminated Pell grants for incarcerated prisoners to receive post secondary education, which had been available since 1965.

The impact of the drug scare would continue during the Clinton administration with the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the largest crime bill in U.S. history. It placed an additional 100,000 new police officers on the street and provided nearly $10 billion funding for prisons. It also eliminated Pell grants for incarcerated prisoners to receive post secondary education, which had been available since 1965.

The increased funding, extra police officers and prosecutors led to the largest growth in prisoners in world history. The incarcerated population in the United States grew from a little over 500,000 in 1980 (319,598 in prison, 182,288 in jail) to over 2.3 million by 2013. The War on Drugs led to the imposition of crime policies which would put America in the position of having only 5% of the world’s population and over 25% of the people incarcerated.

Publication Date: July 27, 2015

Sources

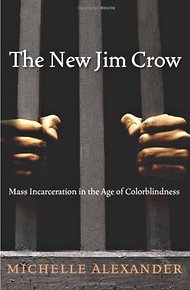

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press, 2012

- Mayer, Marc. Race To Incarcerate. The New Press, 2006.

- Reinarman, Craig and Harry G. Levine, eds. Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. University of California Press, 1997.

- Walker, Samuel; Spohn, Cassia; and Miriam DeLone. The Color of Justice: Race, Ethnicity, and Crime in America. Wadsworth Publishing: 5 edition, 2012.

Reggie Jackson is Head Griot of America's Black Holocaust Museum. He is co-owner of Nurturing Diversity Partners, where he provides training and consulting on diversity, equity and inclusion to institutions around the country. Reggie is a frequent source for local, national and international media and is himself an award-winning journalist on topics related to African American history and the black holocaust. In the past, he worked as a middle-school teacher.

This exhibit was made possible, in part, by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Any views, finding, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the national Endowment for the Humanities. The Wisconsin Humanities Council supports and creates programs that use history, culture, and discussion to strengthen community life for everyone in Wisconsin.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.

[…] The Mulford Act for gun control was sponsored by the NRA and signed into law by Governor Ronald Reagan who was also a member of the NRA. Reagan would later become President of the United States and continue an onslaught of assaults on the Black community. […]