What Does Cultural Appropriation Really Mean?

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Ligaya Mishan, The New York Times

And as accusations of improper borrowing increase, what is at stake when boundaries of collective identity are crossed?

[…]

“CULTURAL APPROPRIATION” IS one of the most misunderstood and abused phrases of our tortured age. Such a slippery verb, “appropriate,” from the Latin ad propriare, “to make one’s own.” It doesn’t carry the forthrightly criminal aura of “steal.” Embedded in it is the notion of adapting something so it is particular to oneself, so that it no longer belongs to or is true to the character of the original source — is no longer other but self. The British sociologist Dick Hebdige uses the word in his 1979 study “Subculture: The Meaning of Style” to describe how fringe groups transform the most mundane objects into emblems of resistance, like punks with safety pins — household items stripped of their practical function when stabbed through the cheek, ornament and weapon at once. These objects are deliberately mishandled, misappropriated, so they become, Hebdige writes, “a form of stigmata, tokens of a self-imposed exile.”

Transformation is more profound than theft, which can make appropriation a useful tool for outsiders. Still, what most people think of today as cultural appropriation is the opposite: a member of the dominant culture — an insider — taking from a culture that has historically been and is still treated as subordinate and profiting from it at that culture’s expense. The profiting is key. This is not about a white person wearing a cheongsam to prom or a sombrero to a frat party or boasting about the “strange,” “exotic,” “foreign” foods they’ve tried, any of which has the potential to come across as derisive or misrepresentative or to annoy someone from the originating culture — although refusal to interact with or appreciate other cultures would be a greater cause for offense — but which are generally irrelevant to larger issues of capital and power. (The law, too, draws a distinction between commercial and personal use: For years, the song “Happy Birthday” was under copyright — until a 2015 legal decision invalidated the claim — which meant that people had to pay thousands of dollars in licensing fees to include it in a play, movie or TV show or to publicly perform it in front of a large audience; but anyone could sing it to family and friends for free.)

Some argue that cultural appropriation is good — that it’s just another name for borrowing or taking inspiration from other cultures, which has happened throughout history and without which civilization would wither and die. But cultural appropriation is not the freewheeling cross-pollination that for millenniums has made the world a more interesting place (and which, it’s worth remembering, was often a byproduct of conquest and violence). It is not a lateral exchange between groups of equal status in which both sides emerge better off. Notably, champions of cultural appropriation tend to point triumphantly to hip-hop sampling as an exemplar — never mentioning the white bands and performers who in the ’50s and ’60s made it big by co-opting rhythm and blues, while Black musicians still lived under segregation and, not unlike Solomon Linda, received dramatically less recognition and income than their white counterparts and sometimes had to give up credit and revenue just to get their music heard.

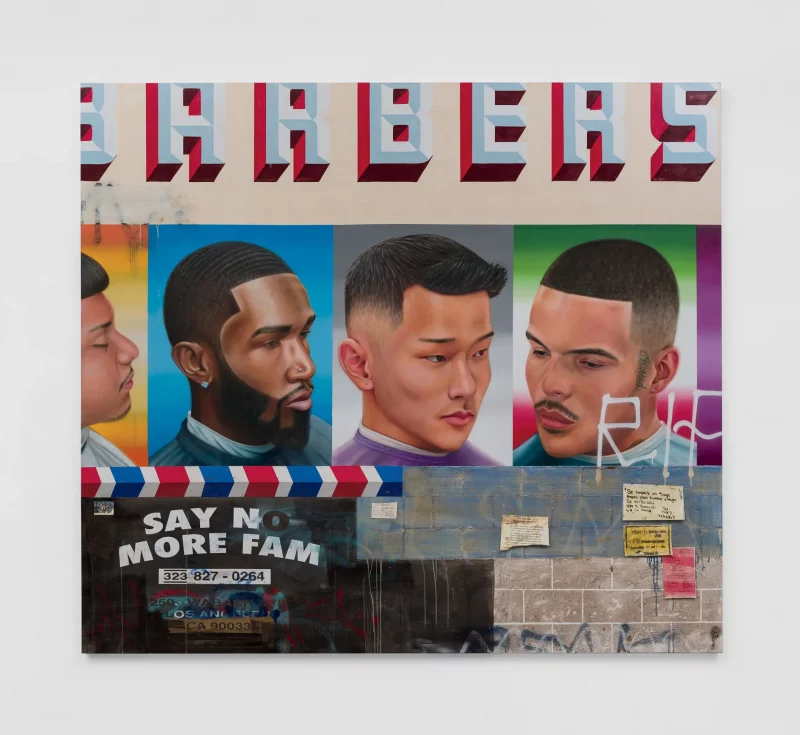

The American cultural theorist Minh-Ha T. Pham has proposed a stronger term, “racial plagiarism,” zeroing in on how “racialized groups’ resources of knowledge, labor and cultural heritage are exploited for the benefit of dominant groups and in ways that maintain dominant socioeconomic relationships.” This is twofold: Not only does the group already in power reap a reward with no corresponding improvement in status for the group copied from; in doing so, they sustain, however inadvertently, inequity. As an example, Pham examines the American designer Marc Jacobs’s spring 2017 fashion show, mounted in the fall of 2016, in which primarily white models were sent down the runway in dreadlocks, a hairstyle historically documented among peoples in Africa, the Americas and Asia, as well as in ancient Greece but, for nearly 70 years, considered almost exclusively a marker of Black culture — a symbol of nonconformity and, as a practice in Rastafarianism, evoking a lion’s mane and spirit — often to the detriment of Black people who have chosen to embrace that style, including a number who have lost jobs because of it. Jacobs’s blithely whimsical, multicolored felted-wool locs, Pham argues, “do nothing to increase the acceptance or reduce the surveillance of Black women and men who wear their hair in dreadlocks.” Removed from the context of Black culture, they become explicitly non-Black and, in conjunction with clothes that cost hundreds of dollars, implicitly “elevated.”

Keep reading this thorough analysis by Mishan.

Cultural appropriation has been a serious issue within fashion. Black Americans have also been falsely accused of appropriation.

Don’t forget to check out our breaking news page.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.