Why History Museums Are Convening a ‘Civic Season’

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Christopher Wilson, Smithsonian Magazine

As the Smithsonian Institution joins with hundreds of other history organizations this summer to launch a “Civic Season” to engage the public on the complex nature of how we study history, it’s exciting to be at the forefront of that effort.

This year, the observation of Memorial Day took on a decidedly different tone. Because May 31 and June 1 also marked the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, the traditional acknowledgement of U.S. veterans who have died in service to the nation was also marked by conversations of the historical roots of racial injustice and how it manifests today. Many Americans found room in their commemorations to recognize victims of violence and those murdered a century ago when racist terrorists attacked and burned the Tulsa’s Black neighborhood of Greenwood to the ground.

This reinterpretation of one of America’s summer celebrations left me thinking about the way public historians teach about our past, and that what we remember and commemorate is always changing. Museums and public history organizations strive to use stories of the past to empower people toward creating a better future.

This motivation gets at why, this summer, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is joining other U.S. museums to inaugurate the first Civic Season. The idea is to establish the period beginning with June 14, Flag Day through the Fourth of July, and includes Juneteenth and Pride Month, as a time of reflection about the past and for dreaming about a more equitable future.

History is taking a place on the front burner of the national conversation. Scholars and educational organizations who focus on deep analysis of the past are unaccustomed to being this topical. They are certainly not used to being at the center of political and ideological battles that pit historical interpretations against one another.

Flashpoints include: The 1619 Project, named for the year when the first 20 enslaved Africans landed by ship in Virginia; the 19th-century phrase “Manifest Destiny,” as westward expansion came with the genocidal dispossession of Native peoples; the reconsideration of statues of Confederate soldiers in town squares; and the rethinking of the reputations of many of our Founding Fathers in the context of their participation in the brutality of slavery….

Photo: In 1963, members of the Congress of Racial Equality train Richard Siller (left) and Lois Bonzell to maintain their stoic posture and endure the taunts, threats and actual violence they would encounter in the real sit-ins. (Bettman, Getty Images)

We wanted to use performance and participation to complicate this experience and replace the assurance and moral certainty visitors brought to the object, with confusion and indecision. We wanted to find a way to replace the simplicity of the mythic memory of a peaceful protest everyone could agree with, and complicate it with the history of a radical attack on white supremacist society.

So…we decided to re-create the training experience of the nonviolent direct action workshops like those Reverend James Lawson had begun in 1959 in Nashville where he taught Ghandian tactics to eventual movement leaders like John Lewis and Diane Nash.

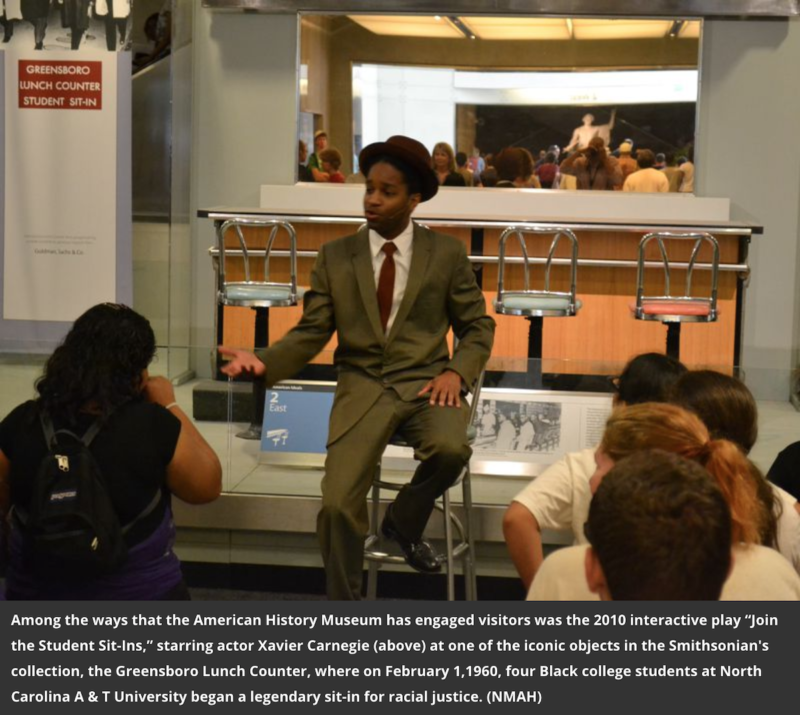

These training sessions included role playing exercises where recruits would practice the conviction and tactics they needed to endure the taunts, threats and actual violence they would encounter on a real sit-in. We asked the assembled audience a simple question: “What’s wrong with segregation?” Our actor Xavier Carnegie played the character of a veteran of several sit-ins and a disciple of nonviolent direct action principles, reminding visitors that it was 1960, and segregation in private businesses was perfectly legal.

Read the full article here.

Learn more untold stories of the Civil Rights Movement, check out the exhibits in our gallery I Am Somebody: The Struggle for Justice.

More Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.